The long-awaited follow-up to the 2017–19 National Survey of Family Growth has been released, with data collected from January 2022 to December 2023. As far as I’m aware, the only other nationally representative survey with publicly accessible sexual behaviour data released post-COVID is the General Social Survey, which in 2022 saw the past-year sexless rate for men and women aged 18–29 fall to 12%. The main issue with this however is the same as that of the famous 2018 data—the meagre sample size1. Also, something wacky happens to men's political views in 2022 after applying weights. This issue could potentially be affecting other questions to an extent too.

Before diving in, some caveats. Response rates for household surveys have been on the decline, and COVID has only exacerbated this trend:

The NSFG response rates for 2022-2023 are markedly lower that the response rates for the last 2-year data collection period of 2017-2019. Some of the sharper decline in participation can be attributed to the effects on society of the COVID-19 pandemic, from respondents’ willingness to participate to the ability to recruit and retain interviewers.

Nonetheless, they explain how a ‘responsive design’ successfully reduced the risk of nonresponse bias, and the sample size for 18–29s (1,741) is still about 7-8x the size of the 2022 GSS sample.

There was also a shift to a ‘multimode design’ involving both online and face-to-face interviews, and they caution against haphazard comparisons between its results and those of prior surveys:

Data users are encouraged to exercise caution when making comparisons to prior years of data collection and interpreting any differences. The multimode design is very different from the prior FTF-only design, and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented experimental evaluation of the impact of the multimode design on survey estimates. Like other surveys that had to change to a new design due to the disruption of FTF interviewing, changes in estimates from before and after the pandemic are confounded by real changes in the population, measurement differences, and nonresponse, among other possible sources of error (coverage, sampling, and processing). As a result, some estimates may show larger differences from the 2017-2019 NSFG and earlier data compared to those observed between prior data releases.

During the first four weeks of each quarters, data was collected through web surveys. This was followed by an 8-week period of FTF data collection targeting individuals who hadn’t yet completed the web survey while keeping the web survey open as an option. Finally, they used increased incentives to try and get anyone who hadn’t yet completed the survey to complete it using either mode. After all was said and done, about 3/4ths of those who completed the survey had done so online.

Fortunately, they included a variable that allows the sample to be filtered by survey mode. I tested for differences by survey mode, and found significantly higher rates of sexlessness among the online respondents.

This could indicate two possibilities. One is the presence of social desirability bias, which might influence FTF responses more than the relatively anonymous online responses; the other is differences in characteristics between those who participated in the traditional FTF interview and those who completed the survey online.

When it comes to social desirability bias, a few studies have found that online surveys are more susceptible to this than FTF interviews (Heerwegh, 2009; Berzelak & Vehovar, 2018). Interestingly, if it is having a large impact on the results, then women must be at least as ashamed to admit to being sexless as men, as women who completed the survey online had a similarly higher sexlessness rate to offline respondents as did men.

I found that online respondents were more educated and white on average, as were respondents in general compared to an earlier survey. One study found that online survey respondents were lower in openness to experience than FTF respondents, and this trait correlates with sexual activity.

While weighting can do a good job of accounting for these demographic characteristics, differences in personality/behaviour will likely remain, and there may be proportionally more people of a certain type than there were in previous samples, rendering the results less comparable to those of prior years as the above quote warned.

Survey respondents have also been found to score lower in openness and higher in intelligence and conscientiousness than nonrespondents, and Bosnjak et al. (2013) found that online panel members who participated in both surveys were lower in extraversion, so a high nonresponse rate could introduce bias that is difficult to fully account for as well.

It’s hard to know exactly how to proceed, but it might be prudent to compare only FTF responses to prior survey years for consistency’s sake. Unfortunately, this limits the sample size substantially, but it’s still superior to the GSS sample size by a factor of about 3. While restricting the sample to FTF respondents could introduce bias in the opposite direction, higher than usual nonresponse bias in the overall sample could help to counterbalance this, and it’s probably better to be conservative than to risk producing another misleading viral graph.

Does this survey replicate the ‘post-COVID sex boom’?

For the percentage of respondents reporting no opposite-sex sex partners in the past year, we see little change among 18–29 heterosexual & bisexual2 women, and a rise among 18–29 men from 23.4% to 31.5%, though this probably isn't statistically significant, nor is the gender gap. When including online responses, the percentages rise to 39.2% for men and 33.4% for women.

We can also examine virginity rates. Most people’s reference point is the 2018 GSS graph showing 18–29 men’s virginity shoot up to 27%. This graph is still regularly posted, often accompanied with the suggestion that ‘it’s probably even higher now’. As noted earlier however, the apparent tripling of the male virginity rate from 2008–18 was mostly a matter of noisy data3. Just thought I’d get this out of the way to avoid confusion about the data below.

Here we see a slight increase from around 15% to 19.5% for men and 18.4% for women. The percentages when including online responses are 26.6% and 24.5%, respectively. So at most the virginity rate for young men rose to what people thought it was in 2018, but this wouldn’t be a gendered trend as it’s typically assumed to be.

It appears then that the last GSS survey underestimated the sexlessness rate for young adults just as earlier surveys painted an exaggerated picture. Of course, this doesn’t matter much since it didn’t reach millions of eyeballs in the same way.

The use of the 18–29 age bracket has been criticized by some for being overly heterogeneous, with sexlessness and singleness declining significantly from the youngest ages to the mid-20s. It shouldn't affect trends much, but it might dilute changes that are more pronounced among younger/unpartnered individuals, and numbers regarding more specific age groups might be more insightful.

For men aged 18–24, the past-year sexless rate rose from 32% to 40%, while women's remained about the same at 29%. Including online respondents these figures rise to 48% and 42%. Among 25–34s, men and women experienced a similar rise of about 6% to 18% and 17%. Including online respondents, 21% and 20%.

The 2023 data for high schoolers in the YRBS has also been released. There was no change from 2021, likely due to the percentage of students who’d ever had sex or were currently sexually active dropping more than it would have ‘naturally’ in 2021.

It's over for Chad (Part 2)

In a previous article debunking the Chadopoly meme (that men who are in the top 5% of physical attractiveness are sexually monopolizing virtually the entire population of women under 30), I referenced three black pill papers which had cited the Harper et al. (2017) study in support of the Chadopoly narrative.

Since then, it has also been cited in ‘The grim view of online dating—Rethinking Tinder’. As the title should make clear, this is another black pill paper, once again arguing—or largely narrating through a fictional story, which is at least fitting—that dating apps are facilitating Chadopolies, and also that they’re a ‘problem for justice’ that should be a ‘public and political concern’, and that we should ‘take measures to correct the inequalities in online dating’. People continue to spiral into hysteria over the Chad bogeyman. As we will see once again, however, this is entirely unnecessary.

Somewhat bizarrely, it describes the findings as showing that Chad has ‘even more sexual partners than such men had a decade ago’:

While many young men suffer from involuntary loneliness, those men who have many sexual partners—the rare winners in online dating—have even more sexual partners than such men had a decade ago.

This is despite the study comparing the 2002 and 2011–13 surveys, with the latter barely capturing any of the period during which dating apps had been released, let alone popularized.

It has also been cited in the intro to a recently published book by Mad Larsen titled ‘Stories of Love from Vikings to Tinder: The Evolution of Modern Mating Ideologies, Dating Dysfunction, and Demographic Collapse’.

In this intro, another falsehood is presented:

Such economic freedom—in combination with gender equality, adherence to confluent love, and hypercompetitive dating markets—influences women to increasingly channel mating opportunities to the top 5% of men, a group whose access to new sex partners has increased by 32%. The same American study showed an equivalent reduction in sex partners among the men at the bottom.

I don’t know if they are misremembering or just assuming nobody will check, but the study did no such thing. It could be that they uncritically accepted this part in Lindner (2023) as true:

Thus, while the amount of male sex that was had was unchanged, more of the sex was consolidated into ‘extra sex’ for the top 5–20% of men.

For this to be true, it would indeed need to be the case that men ‘at the bottom’ had taken a hit to their body count. In the Chadopoly article, I argued that it was mathematically implausible on its face that this would be offset by a reduction in partners among the ‘bottom men’, and described how there actually was a significant rise in the mean number of sex partners reported by men overall, and also no rise in sexlessness:

The overall mean partner counts for 2002 and 2011-13 were 8.61 and 9.85, respectively. This increase was significant at p < 0.005. There was also no change in the percentage reporting no female sex partners in the past year (21.1% of men in 2002 and 21.5% in 2011-13, inflated slightly by homosexuals).

I guess Lindner assumed that since the median hadn’t changed, there hadn’t been an overall increase? Otherwise, I couldn’t say where this idea came from.

These misrepresentations aside, there have now been four surveys conducted since the 2011–13 one. You'd think given how heavily the Chadopoly narrative centres on dating apps that these surveys would be especially interesting.

As I demonstrated in that article, however, subsequent data didn’t show a continuation of the apparent trend. The latest survey will likewise do little to make black pill scholars happy, as if anything it shows a continuation of the Chadcession which was hinted at by the previous survey. This holds true whether online respondents are included or not4.

In the surveys prior to 2015–17, the age range was 15–44, so I’ve restricted the age range to this in the post-2015 surveys for consistency. That said, the age range of 15–44 is hardly ideal for testing the Chadopoly narrative. Even if the most promiscuous younger respondents had grown more promiscuous, this could be obscured by older respondents who will have had more time to accumulate more partners56, and less of them will still be pursuing a ‘player’ lifestyle. Nonetheless, I also tested this using three-year age bins within the 18–29 age bracket, but evidence for this narrative remained elusive.

We also find little evidence of Chadopolization among 18–34s when comparing the sex partner distributions of men and women (this graph uses data from both survey modes). While slightly more men report having 0 opposite-sex sex partners in the past year, it’s important to remember that there are also slightly more young men than women in the US, and also, relationship age gaps could contribute. There are slightly more men with 4+ partners, but the numbers don’t quite add up as there aren’t enough women reporting 1–3 to account for them.

Adding to the growing pile of actual outcome data which continues to be ignored in favour of making overly simplistic extrapolations from swipe imbalances, we also have the question7:

Had sex with someone they first met on the internet in past 12 months.

Breaking the sample down by sexual orientation, we find that only around 5% of heterosexuals reported having done this, without the gender imbalance predicted by the Chadopoly narrative. The rest speaks for itself.

Impossible changes across surveys

For those who would question the decision to exclude online respondents, there is a way to be confident that the increases in sexlessness observed in the overall sample aren’t real.

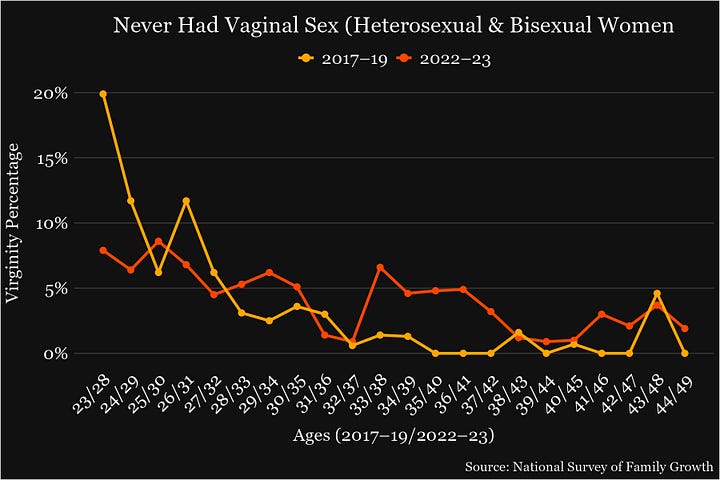

In the 2022–23 survey, virginity rates were the same or even higher than those of individuals five years younger in the 2017–19 survey. It doesn’t make sense for virginity rates to be any higher than they were in 2017–19 among people five years younger, as this would represent roughly the same birth cohort8, and you can’t unlose your virginity.

We also observe a significantly higher average sexual debut age in the same cohort. While some would've had sex for the first time since five years earlier—at an age above the average, which could raise it somewhat—we don't see that much shift in the average beyond the early-mid 20s in the each survey, and there’s not much room for virginity rates to drop past the late 20s (and again, if anything we see a rise across surveys within the same cohort).

It’s also worth mentioning that the virginity rates for individuals aged 15—18 is higher in the NSFG than it is in the 2023 YRBS.

Summary

Overall, the data suggests a modest increase in sexlessness, which aligns with expectations of COVID shaking things up, as well as the much-touted though often overstated sex recession. There was a sharp spike when including the online responses, but it’s probably best to err on the side of caution as the user’s guide suggested, especially considering the seemingly impossible increases in virginity across surveys.

This is probably not the fault of Chad, as despite the Chadopoly narrative only growing in popularity, an examination of the data beyond surface level memes continues to expose it as a cope. There is no evidence of a growing Chadopolization whereby the most promiscuous men (who btw aren’t actually much more Chad looking than the average guy) are racking up ungodly body counts.

In this case 229 for 18–29s who received a ballot including the sexual behaviour module and answered the question regarding sexual frequency in the past year.

Bisexual women were included as the significant and growing number of women who identify as this are usually exclusively heterosexual in their sexual behaviour, as well as generally more sexually experienced, so restricting the sample to heterosexual women actually increases their sexlessness rate somewhat even for opposite-sex partners.

Beyond this, the percentage was inflated by the failure to filter homosexuals out of the sample despite the question pertaining strictly to female sex partners, and also partners before turning 18 not being captured unless they were encountered in the past year.

Though for the 95th percentile the partner number (35) is slightly higher when excluding online respondents.

The average age among those in the 95th percentile or above in lifetime opposite-sex sex partners was 38.3, compared to 31.7 among the overall sample.

There’s also the fact that the NSFG has a cap of 50 for the lifetime sex partners question, so if there was a growing Chadopolization at the 95th percentile or above it’d be hard to detect.

It was asked of people who’d had sex, but I included NAs as 0 to get the overall percentage.

This is being a bit generous too, as the 2017–19 survey started and ended in September.

If rates of sexlessness are rising in both men and women, that doesn't mean that something like "Chadopoly" is wrong entirely. Since men and women's sexuality is different, as you pointed out to contradict some incel claims, it could be that males are having less sex because female standards are rising and they aren't chad, and females are having less sex because there aren't enough chads to go around and they won't settle for anything less.

I appreciate that you want to debate the black pill by using actual arguments instead of the usual platitudes and attacks of feminists and other "bluepillers" but you still seem to make the mistake of underestimating the effects of physical attactiveness using data that's hard to take seriously and making disingenuous arguments using autism and incel shooters which are outliers and not by any mean representative of the vast amount of men struggling with dating and sex.

In economics if the price of a resource (in this case sex) is too high and the supply is limited, the distribution will be mostly concentrated to a few people, so the chads may not be fucking the entire population of women under 30, but if you aren't "Chad" having a good sex life or being in a relationship with a desirable woman (not necessarily a super model, just not fat, not ugly and younger than 30) is very hard.

I think we should all accept the reality that in sex and dating, looks, status and money are first and everything else is second, and the trend in the west is that as women become more successful, their standards increase and they marry a lot less because most available men aren't attractive enough for them, hence why lower status men have to import wives from poorer countries, go "passport bro" or stay single, couple that lower sexual freedom and the result is most men will have little access to sex (with desirable women at least) and this situation could get pretty ugly, as it is always the case when competition for a resource that could be considered a biological necessity is brutal.

I also encountered the anomalies with the ever-had-sex question by birth cohort on the 2022-2023 NSFG. https://borncurious.blog/p/survey-quality-is-declining-because

In addition to the hypotheses suggested by Nuance Pill, I suggest a third: that there are people who just want to collect the $40 for completing the NSFG without spending the hour it takes to fill out the questionnaire, so they say they have never had sexual intercourse in order to skip most of the survey.