A common sentiment online is that height is fixated on by women to the near exclusion of all other features, and as a consequence tall men are the kings of the dating world, while for short ‘kings’ it never began.

Those of a more ‘black pilled’ persuasion are convinced that it’s now 6 feet or bust, often referred to as the ‘6 foot rule’:

Some conclude that for the depraved female species, the manlet cutoff might as well be under 6 foot even, thanks to hypergamy.

There are even stories of men flying to the other side of the world to undergo life threatening surgery just to gain an inch or two.

A common rejoinder to men who complain about height is to “just take a trip to the grocery store bro, there’s tons of short guys out there walking with their gfs”, and while this may be true, it’s also not a convincing argument, and doesn’t negate the possibility of an effect of less dramatic than one which completely excludes manlets from the dating market.

To what extent is this fixation on stature warranted, is it grounded in factual reality, or just a manifestation of insecurity? To get a grasp on the nature and strength of women’s preferences for height, let’s begin with a brief review of the literature.

Looking at what they say

Salska et al. (2008) drew on data from Yahoo Personals personal advertisements and calculated the largest and smallest acceptable sexual dimorphism ratio using people’s own height and their stated shortest and tallest acceptable height in partners. The tallest man women would date on average was 75.3”, while the shortest was 68.9”, just below the average height in the sample (70.7”). The tallest woman a man would date was 69.8”, and the shortest was 60.6”, while the average height in the sample was 65.1”. Converted to sexual dimorphism ratios (1.1 would indicate the male partner is 10% taller than the female partner), men’s preferred range was 1.01-1.17, while women’s was 1.06-1.17.

A pattern established in previous studies was also replicated, with taller women and shorter men preferring smaller sexual dimorphism ratios, perhaps as they realize they need to compromise to maintain a sufficient dating pool. Some were probably averse to the idea of dating someone at the extreme ends of the continuum. Overall, 24% of men indicated that their tallest acceptable partner height was taller than them, 23% that it was as tall as them, and 53% that it was shorter than them. For women on the other hand, 89% demanded that their date be taller than them, with 7% open to men of equal height, and 4% to shorter men.

They then did their own survey among 133 male and 249 female undergrads. Women stated that the ideal male partner was 5’11.3”, while the average man in the sample was 5’9.1”—almost one standard deviation shorter. Men favoured women who were 5’5.7”, while the average women in the sample was 5’5”—less than an inch shorter. Ideal height preferences correlated at .52 with women’s and .42 with men’s own height. Women were most willing to date men who were 5’10”-6’0”, and men were most willing to date women who were 5’6”-5’8 . The penalty for shortness for men was greater than the advantage for tallness. Women reported an ideal sexual dimorphism ratio of 1.1, and men of 1.05. These correlated with their own height at -.58 and .59, respectively. 100% of women and almost all men stated that the male partner being taller was ideal.

Swami et al. (2008) found in a sample of 426 women and 425 men an ideal partner height of 179.75 cm for women, about 4 cm taller than the average man in the sample (175.78 cm). Men’s ideal partner height was 167.64 cm, which was about 1 cm taller than the average woman in the sample (166.51 cm), and the difference wasn’t statistically significant. The average sexual dimorphism ratios desired by women and men were 1.08 and 1.05, a significant difference. 96.9% of women and 91.5% of men indicated that the male partner should be taller. Height correlated with ideal partner height at .52 for men and .44 for women, and with ideal sexual dimorphism ratio at .42 for men and -.75 for women. They also found an association between height preferences and endorsement of traditional masculine gender roles, albeit a small one and only for a couple of the subscales.

In Courtiol et al. (2010a), most females ranked the tallest stimuli (190 cm) first, while men’s preferences were more variable. For both genders the quadratic model was a better fit, demonstrating the presence of a ceiling effect. According to the ‘homogamy preference function’, for every 1 cm increase in women’s height their preferred height rose by 0.77 cm. For men this was 0.6 cm. Women were predicted to prefer males 3.5-6.9 cm taller than average, while men were predicted to prefer women 0.8-4 cm above average.

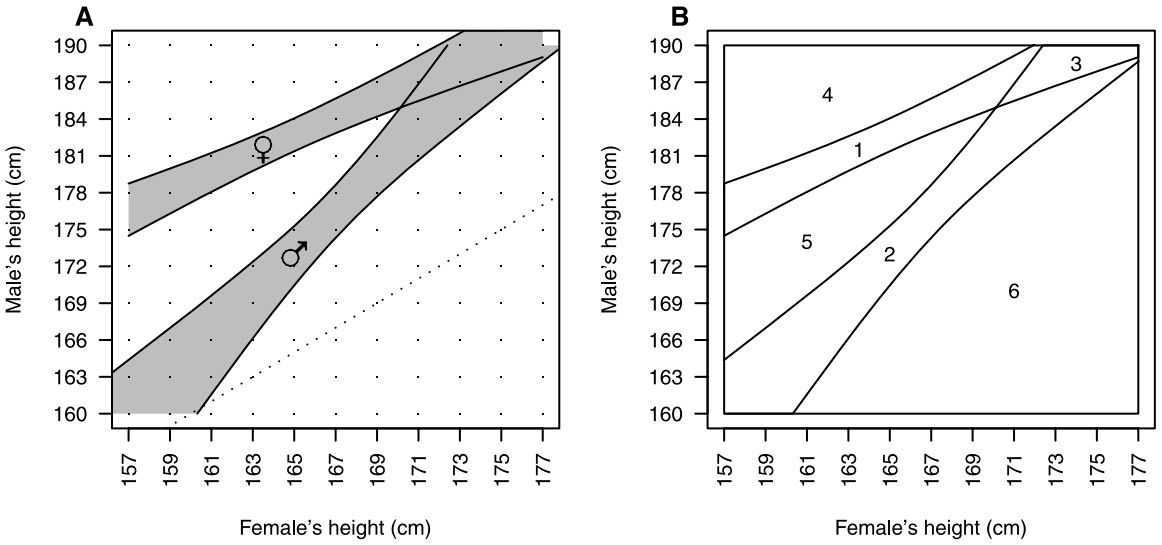

In the figure below, zone 3 is where the preferences of both partners are satisfied—a small area inhabited only by the tallest men and women. If people adhered strictly to these preferences, almost nobody would ever pair up.

Stulp et al. (2013) found that women preferred a height difference of 13.45 cm, while men preferred one of 12.11 cm. In respect to minimally acceptable partner height, women on average required at least a 3.72 cm difference, while men were open to a virtually non-existent 0.05 cm difference. Women were willing to accept a partner up to 25.15 cm taller, while men were willing to accept a woman up to 25.94 cm shorter. Overall, men were open to a larger height range, and while women were more tolerant of heights above their preferred height than below, men were more tolerant of those below than above.

People’s height correlated positively with men’s and women’s preferences at .47 and .54, and with men and women’s preferred differences at .69 and -.49.

Yancey & Emerson (2014) drew on data from Yahoo dating profiles as well as conducting an online survey among university students. Among the Yahoo profiles, 57.1% of women compared to 40% of men indicated that height mattered in seeking a date (d = 0.35). While for men greater height correlated with acceptance of any height, the opposite was true for women. 1.3% of men wanted to only date women taller than themselves (beta subs?) while 13.5% required they be shorter. 1.7% of women wanted to only date men shorter than themselves (Amazonian doms), while 48.9% required they be taller.

In their local sample, women scored higher (4.43) than men (3.63) on a scale measuring importance given to height. This variable was negatively correlated with height for men but positively for women, and their sexual dimorphism ranges followed the typical pattern. While 37% of men required that women be shorter, 55% of women required men be taller. They calculated the average of the shortest and highest height ranges of respondents as a proxy for the average preferred height. The average height desired by women was 69.45 inches, and for men 64.48 inches. Since the average height of men and women in the US were 69.4 inches and 63.8 inches, they conclude that “Our data suggest that both men and women have realistic height expectations of prospective dating partners”.

In the qualitative analysis, they find that most explanations for why women preferred taller men related to ‘societal expectations or gender stereotypes’, concluding that they ‘seem to offer a more comprehensive explanation of the findings of these results than notions of good genes and biological/economic advantages’. One of the explanations provided was quite black pilling, however:

Although I am short, I am not attracted to short men. I could meet the most attractive man, but if he is not at least 5′7, I am not interested. Tall men represent protection. I feel safe for some reason. (5 feet 1 inches White woman)

What they do

Some might say that this is all well and good, but self-reported preferences are notoriously unreliable. As the saying goes: ‘look at what they do, not what they say’. To what extent do these self-reports translate to real world decisions, does height play a large role in who women go for?

First off, studies on lonely hearts columns in newspapers and magazines have shown a positive effect of height on response rates to men’s advertisements (Lynn & Shurgot, 1984; Campos et al., 2002; Pawlowski & Koziel, 2002).

Another avenue for assessing this is through speed-dating experiments. Stulp et al. (2013) analyzed data from the ‘HurryDate’ speed-dating service, with a final sample of 2,601 men and 2,847 women.

First, the reported preferences of participants. 5.9% of women were open to partners as short as 4 feet, compared to 29.3% of men. Incel wiki’s interpretation of this finding that most women (and men) don’t want to date a literal dwarf: “Over 94% of women will reject a man solely for him being too short”. 29.7% of women were open to partners as tall as 7 feet, compared to 24% of men. Incel wiki’s interpretation: “30% of women believe there is no such thing as a man being ‘too tall.’” The preferred height range was wider for men (24.4 cm vs. 18.7 cm, d = 0.74). Height also correlated with both minimally and maximally preferred heights for men (.35, .53) and women (.4, .42). Men’s average minimally preferred height difference was 0.02 cm, while women’s was 8.3 cm (d = 1.21), so only women were typically concerned with the man being taller, while men tended to be okay with being heightmatched. Men preferred a slightly smaller maximum height difference of 24.7 cm vs. 27.9 cm, d = 0.47).

So all in all, nothing too out of the ordinary from what we’ve seen so far. Interestingly, the incel wiki seems to be fine with relying on self-reported preferences in this case. Importantly, however, the study also measured how these preferences correspond to actual choices. What they found was that potential partners incurred only a small penalty for falling outside of someone’s preferred height range. The probability of a man giving a ‘yes’ to a speed-dating partner was 47.9% for women within their preferred height range, and 42.8% for those falling outside of it, while women yessed 32.2% of men within their preferred height range, and 25.4% of those without it.

They also measured how much the likelihood of yessing partners was reduced by how much they strayed from these parameters. For men, a one inch deviation predicted a 40% yes rate, while a 5 inch deviation predicted a drop to 34.3%. For women, a one inch deviation predicted a 24.8% yes rate, while a 5 inch deviation predicted a drop to 16.8%. A significant sex interaction effect was detected for both of these analyses with women’s choices being more influenced by their stated preferences. The participants’ ability to assess a speed-dating partner’s height was probably adequate, as speed-daters spent several minutes beforehand interacting while standing, and standing height correlates almost perfectly with sitting height and arm length.

We can also see from the visualization below that women were more tolerant of men falling above their preferred height range than below, while the reverse was true for men:

The standard deviation of heights which yesses were given to were on average 2.45 for men and 2.35 for women, a statistically significant albeit small difference (d = 0.15). This wasn’t just a result of differing SDs for male and female height, either. This measure of tolerance correlated with the reported preference range of men and women, although again very weakly (.07 for men, .064 for women).

Men were most likely to yes women when they were 7.1 cm shorter, while women were most likely to yes men when they were 25.1 cm taller. Short men also seem to have been aware of their lower desirability as they also tended to be a bit less selective. Matches were most likely when there was a difference of 19.2 cm (which shouldn’t be mistaken to mean it was the most ‘common’ height difference of matches). Still, matches weren’t drastically more likely for tall than short men, rising from about 12% to 17%.

Both men and women’s height correlated with the average height of their matches at .13 and .11 respectively, showing some degree of assortative pairing.

It should be noted that the effect of height was quite minor overall. To put it in perspective, Belot & Francesco (2006) in a study of about 3,600 speed-daters in the UK found that while 5 cm (almost 1 SD taller) increased men’s chance of being chosen by almost 1% (a 9% increase), being overweight reduced women’s chance of being chosen by 16% (a 70% decrease).

Hitsch et al. (2010) analyzed data from approximately 22,000 US online daters. Men standing at 6’3-6’4 received 65% more first contact e-mails than 5’5-5’6 men, but once again the advantage of tallness wasn’t as big as the disadvantage of shortness. It was also found that the height of matches correlated at .16. It’s questionable whether online dating represents revealed preferences however, as seeing someone’s height in text and making decisions based on this is arguably more similar to stating your ideal height preferences.

How preferences correspond to actual pairing

So, we’ve established that women’s stated height preferences have some predictive validity. This is certainly progress, but what we’re truly interested in is actual pairing. Stated preferences may predict revealed preferences, but to what extent do revealed preferences predict actualized preferences?

Courtiol et al. (2010b) found that though women’s actual partners were within about 1 cm of their median preferred height, there was very little association between preferred and partner height for each individual. If anything, men’s preferences were a stronger predictor of their partner’s height (the same was true for BMI). The preferences weren’t associated with the length of the relationship, deeming it unlikely this was simply a result of adjusting preferences to their partner’s characteristics.

Stulp et al. (2013) examined the height of the parents of 18,819 babies born in the UK. It was discovered that for every cm increase in female height, partner height rose by 0.19 cm, and for every cm increase in male height, partner height rose 0.17 cm—a far cry from the preferred increase of 0.77 cm and 0.6 cm as seen in the earlier Courtiol et al. study. Men were taller than their partners 92.5% of the time. While this may sound impressive and is more frequent than you’d expect by chance, random pairing would still result in this occurring 89.8% of the time. Bins in which women were substantially taller than the male were much less likely to occur compared to what random pairing would produce, so even when the male-taller norm was violated, it didn’t tend to be by much. When it came to the ‘male-not-too-tall norm’—defined here as men being at least 25 cm taller than their partners—13.9% of couples violated it compared to the 15.7% you’d expect by chance, and again when it was violated it tended to be only marginally so.

Another study (Sohn, 2015) examined 8,000 married Indonesian couples and found a 93.4% adherence to the male-taller norm, while randomly pairing individuals from the same sample produced a rate of 88.8%. When setting an age difference of 5 years however it produces a rate of 91.4%. While this difference is statistically significant, the title stated it was a ‘lack of evidence from a developing country’. Another one (Tao, 2016) found using a model controlling for age, education, and family income that the frequency Taiwanese pairs with a height difference within the range of 5-15 cm was higher than expected by chance, and the number of pairs in the random mating simulation which violated the male-taller norm was more than twice as many as observed in actual pairs.

Stulp et al. (2016) in a meta-analysis on assortative mating for height found a .25 correlation in Western and .21 in non-Western cultures (the difference wasn’t statistically significant, despite some studies seeming to show no effect of height on mate choice in the latter). Interestingly, the previous study by Stulp et al. found after enforcing a male-taller norm in simulated pairs that it produced a median correlation of .34, so this is certainly nothing to write home about.

Are short men excluded from relationships?

Height preferences probably play a role in the pair formation process, as the height of pairs correlates and there are slightly less couples in which the male is heightmogged by their partners than you’d expect if it played no role whatsoever. What we haven’t yet done though is address the central concern—namely how much of a handicap being a manlet is on the dating and marriage market (and how much of a boon being tall is).

We begin with Fu & Goldman (1996), who analyzed data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. The sample consisted of around 5,800 non-Hispanic and non-black respondents who were never married at the time the survey began while they were aged 14-21. By 1991, men below average height had lower rates of first marriage. For the shortest group (2 SDs below average) their chances were reduced by about 35% of that of average height men, and for the ‘short’ group (between 1 and 2 SDs below average) there was a reduction of about 26%. There was no effect of tallness. For women on the other hand there was less of a clear pattern overall, but being very tall reduced their chance of marriage by 21%.

Harper (2000) analyzed the British National Child Development Study, and found among a sample of about 6,000 that the probability of being married in 1991 at age 33 was 7% lower for men in the bottom 9% of height, though men in the bottom 10-19% weren’t significantly less likely to be married, and once again there was no effect of tallness. The probability was 5% lower for tall women.

Murray (2000) looked at data from 1,961 male college graduates born between 1832 and 1879 who were followed until their deaths. All were unmarried upon entering the sample at age 18. Very short men (more than 2 SDs below the mean) were 11% less likely to ever marry, and 45% less likely to marry soon, while very tall men were 15% more likely to ever marry and 40% more likely to marry soon. Men who were simply ‘tall’ seemed to be slightly less likely to ever marry (probably a false positive), while there wasn’t a significant effect of being simply ‘short’.

Cawley (2006) analyzed data from the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (N = 8,039) and Wave I (1994-95) of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (N = 8980). The results for the NLSY97 were that males who stood an inch above the average height had a 4.7% higher odds of having dated than those of average height. For females it was 3.6%. These results weren’t replicated in the Add Health study, where only in a couple of models was there a marginally significant effect.

Hacker et al. (2008) analyzed two samples from the mid-19th century. In the first (N = 9,257), men 1 SD above the mean height were 16% more likely to be ever married than men 1 SD below the mean height. In the second (N = 4,598), height’s effect was only marginally significant, with men 1 SD above the mean height being 13% more likely to be ever married than men 1 SD below.

Stulp et al. (2012) analyzed data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (N = ~3,600) and found no effect of height on men’s number of marriages or chance of being married, but did find a quadratic effect of height on age at first marriage, with average height men marrying earliest.

Weitzman & Conley (2014) analyzed two different cohorts from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, who were aged 23-45 in 1986 or 2009 (N = 3,033). Short men had partners who were on average 1.58” shorter than average height men, had 269% higher odds of partnering with a woman who was heightmatched, and 1,450% higher odds of partnering with a woman who was taller than them. Tall men had a 95% lower odds of partnering with a woman who was heightmatched, and 100% lower odds of partnering with a woman who was taller than them. The chances of marriage were 18% lower for short men and 9% lower for tall men. Interestingly, they found that after age 30, tall men ‘recouped the losses incurred before their 30s’ and their chances of marriage rise above that of average height men. Also interestingly, short men’s marriages were more stable, as they had a lower hazard rate of separation. They posit that they may be more likely to ‘select out of marriage before it begins’. Finally, while in 1986 92.7% of men were taller than their spouses, in 2009 this was 92.2%, so no sign of a strengthening of the male-taller norm.

Sorjonen et al. (2017) found in a large sample of Swedish military conscripts born between 1949-51 a quadratic effect of height on the predicted hazard ratio for not being unmarried from 1974-2008, with the optimum around 185 cm, or about 7 cm taller than the average height of 178.2 cm. This was largely unaffected after adjusting for the father’s occupational position, own self-rated health, or educational attainment. A small negative association was found between height and hazard for divorce once married, but this was rendered nonsignificant after adjusting for educational attainment.

Yamamura & Tsutsui (2017) found that for Japanese men born before 1965, a 1% increase in height led to a 0.56% higher probability of being married, while for women it led to a 0.56% decrease. For those born after 1965 however, it led to a 1.05% higher probability for men, but it had no effect for women. There was also a negative effect on the probability of divorce, which became stronger in the younger generation.

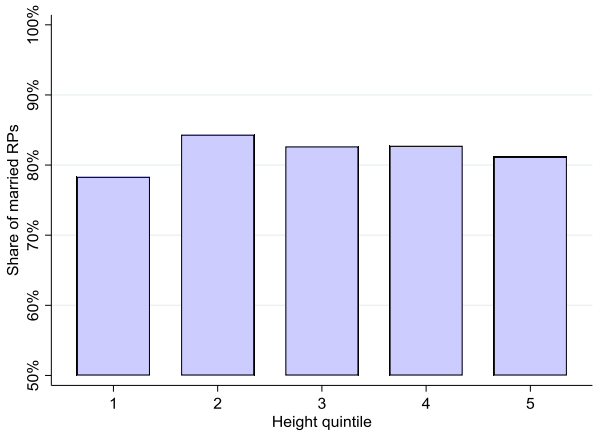

Thompson et al. (2021) employed a sample of 8,324 Dutch men born in the 19th century. They also compared their outcomes with their siblings, with the reasoning that it’d help control for early-life determinants. Brothers with different marital outcomes were 0.14 cm apart on average, while those with the same outcome were 0.004 cm apart. The shortest quintile (20%) of men were 86% as likely to marry than men of average height, while no significant differences were observed among the other height quintiles. The shortest quintile also married latest at 28.1 years, though the differences were marginal at best, with the fourth quintile marrying earliest at 27.7 years.

Survey analyses

There are also a few nationally representative US datasets which weren’t covered here which I’ve decided to take a look at. Let’s begin with the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. This survey is good because it measures the participants’ height directly.

Below we see the difference in height between men and women who were currently married or cohabiting and who weren’t. For men the Cohen’s d values range from 0.07-0.22, with significant results for three of five age groups.

The reason why there was a significant effect for 60-69 women may be due to assortative mating. People tend to pair up with others of comparable socioeconomic backgrounds, and chronic undernutrition resulting from poverty can cause stunted growth and poor health. Shorter people’s partners may therefore be at higher risk of an early demise on average.

Potential secular trends are a valid concern, as for example if height rose but cohabitation & marriage rates fell, this would attenuate the effect of height on relationship status. However, there wasn’t a clear or statistically significant trend in height or relationship status across the survey years among 20-50 non-Hispanic Whites.

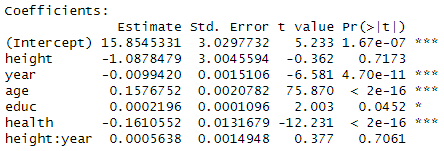

Below are the results of a logistic regression with being in a cohabiting or marital relationship as the dependent variable and height (standardized), ethnicity, age, survey year, and educational attainment as independent variables (ages 20-50).

The resulting beta coefficient was β = 0.06, meaning that a one standard deviation change in height predicts a 0.06 SD increase in the log odds of being in a relationship. Adding a height squared term didn’t improve the fit of the model, meaning no evidence for a quadratic effect whereby very tall men are also less likely to be in a relationship.

Adding a height × survey year interaction term also failed to reveal a significant effect, meaning no evidence that the effect of height has changed over time.

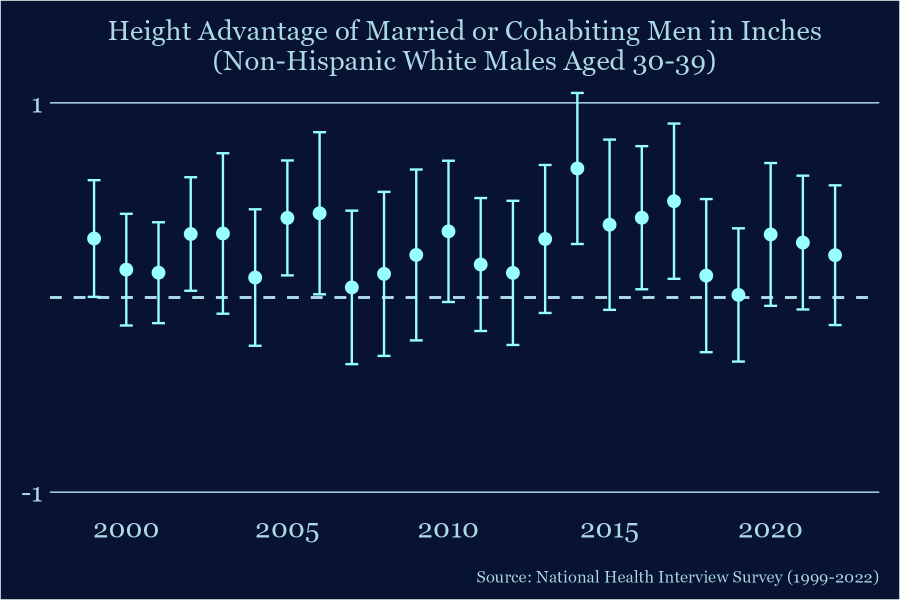

Next up we have the National Health Interview Survey. While height is self-reported in this survey, it has the advantage of much larger sample sizes, allowing for even very small effects to be detected, and unlike NHANES the data past 2016 is publicly accessible, allowing for the testing of the narrative that the importance of height has been amplified post-dating apps. Also, while both men and women seem to overestimate their height by about 1.2 cm on average, self-reported height is highly reliable, tending to correlate at at least .95 with objectively measured height. Older people are less accurate in their reports, perhaps because they had shrunk since they last had their height measured (Tuomela et al., 2019).

We see similar results to those seen in NHANES in height differences by relationship status, with a consistent difference hovering around d = 0.1, though there’s interestingly no effect whatsoever among men in their 20s.

I also found no sign of a quadratic effect, and controlling for other variables didn’t help to produce an effect among 20-29s either.

Increasing the age range to 20-50 yields a standardized beta coefficient of about 0.05, similar to NHANES. The squared term still wasn’t quite significant.

Including earnings in the model reduced the effect of height to about 0.036, though it’s also not available for 2018-22.

Running the same analysis on women, we find a -0.03 β, and a significant but also very small quadratic effect. The optimum seems to be slightly short.

A common narrative online is that online dating has drastically reshaped the dating market to the detriment of physically inferior men. Dating apps (and social media) have accelerated ‘hypergamy’ by giving them an unlimited supply of male attention, deluding ‘4s’ into thinking they’re ‘8s’. It’s also believed that they’ve facilitated a chadopolized hook-up culture, allowing these women to indulge in their insatiable lust for ‘chad d*ck’, and once they get a taste of it they can no longer settle for anything less. You could also argue that because dating apps prioritize visual features over all else, there are now filters in place before you even get the chance to display your other characteristics. Of course apps tend to have literal height filters now too.

We can see from this chart showing how much the heights of 20-29 men in and not in relationships differs from zero across the years however that there’s no sign of an emerging gap in recent years, or ‘the Tinder era’ as some like to call it.

While for men in their 30s there is a more consistent height advantage for men in relationships of about 0.25 inches on average, this doesn’t appear to be increasing either.

To make doubly sure, a regression analysis also failed to find a significant interaction effect for 20-39s.

Below are density distributions of height for 25-34 men in and not in relationships from 2012-22. Notice the double peaks, as some portion of men bump their height up to 6’.

And for the NHANES data for 20-39s.

There was also no evidence for a shift in the strength of the relationship between men’s height and marital status across the 1976-98 surveys. The effect size was also about the same at β = 0.04.

We also see the same pattern whereby taller men in their 20s aren’t more likely to be married.

Something to note is that height may not be associated with relationship status the same for other groups. For blacks, the effect tended to be about 0.03 for men 30 and up, and in contrast to Whites, the only significant effect was for 20-29s (d = 0.09, p < 0.05). For Hispanics, there actually appeared to be a small negative effect which was strongest for 20-29s (d = -0.17, p <0.001). It could be that they’re rapidly growing taller as many are coming from worse environmental conditions. Since younger people are also more likely to be single, this could produce a spurious correlation. On the other hand a logistic regression controlling for age and survey year still showed a negative effect. I’ll leave this an open question.

Relationship quality

Being in a relationship is one thing, but being in a good relationship is another. Do taller men have better relationships, perhaps owing to more mutual attraction and enthusiasm and subsequently more vibrant sex lives? Maybe they are able to score more attractive partners. Maybe they feel less fear of being cucked. There are several studies which can help answer this question.

Stulp et al. (2013) found that partner height correlated with reported satisfaction with partner height in women (r = .19, p = .004) but not in men (r = .065, p = .56). For both genders, partner height differences were curvilinearly related to satisfaction with partner height. For men, the optimum was 8.26 cm shorter, while for women it was 20.93 cm taller.

Sohn (2016) found in two large representative Indonesian datasets that a 10 cm increase in height difference predicted a 3.92 percentage point increase in reporting being very happy. When adding a squared term, neither the linear nor squared term were statistically significant. When looking at marital duration, the association between happiness and height difference had fully dissipated by 18 years.

I’ve also investigated some datasets with questions on relationship satisfaction. In the General Social Survey, a multiple regression analysis on marital happiness among 20-50 males (with a final sample size of 542) yielded a 0.01 β. There's also a question regarding cohabitation happiness (N = 166), which gave a -0.06 β (ns).

In Wave IV (2007-08) of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, at which point subjects will have been between the ages of 24-32, there was no significant effect of height on how happy men were in their relationship (r = -.03), with trusting their partner to be faithful (r = .03), with their partner expressing love and affection (r = .03), number of romantic or sexual partners lived with for 1 month or more (r = .02), or number of marriages (r = 0). Funnily enough, there was a significant negative effect of height on satisfaction with sex life with partner (r = -.08). Maybe manlets are better in bed, but I’d guess it’s a false positive.

A survey called ‘Americans’ Changing Lives’ also didn’t show a significant correlation between men’s height and marital satifaction (r = -.03, N = 930). The same went for a Chinese survey called the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (r = .01, N = 4,558). However, there was an effect for women (r = .06, N = 5,668).

That’s four null results in a row. Overall, some weak evidence that partner height may increase women’s satisfaction, but tall men don’t seem to psychologically benefit from their own height in relationships. Could their partners nonetheless be of higher quality?

Feingold (1982) sought to determine whether taller men’s partners were prettier. A simple correlation failed to reveal a significant effect (r = .12, ns). However when instead correlating height with the relative attractiveness of the partner revealed a significant effect (.27, p < .05). The men with partners more attractive than them were on average 2.6 inches taller than the men with less attractive partners. Another study (Pawlowski et al., 2008) found among 47 rural Polish women a marginally significant relationship between their attractiveness and their partner’s height (r = .266, p = .07). The more attractive women had partners 174.1 cm on average, compared to 170.5 cm for the less attractive women. There wasn’t a significant difference in the height of the two groups however, and if anything it was in the opposite direction. Oreffice & Quintana-Domeque (2010), using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, found that for each 10 pounds on the wife (7% of her average weight), men were 0.14 inches shorter (1% of his average height).

Conclusion

First, we went over some research on mate preferences for height. Several consistent patterns tend to emerge:

Taller men are typically preferred, though it seems like shorter men being disfavoured is a stronger and more consistent finding than tall men being actively favoured. There is an inflection point somewhere above 6’.

Men have wider preference ranges, and women are more punishing towards men falling below than above their preference range. Women also desire larger height gaps.

The vast majority of both men and women’s ideal pairing involves the man being taller than the woman. More women than men state this not just as a preference but a demand.

People’s height preferences are influenced by their own height. Taller people want taller partners, and both tall women and short men report a preference for a smaller height gap.

It’s not always the case that stated preferences predict revealed preferences, but women in various dating environments appear to display a preference for taller men, even if people tend to overestimate how narrow their acceptable range is (and may not be very good at gauging what say 6’0 actually looks like irl).

These preferences don't appear to be strongly linked to actual pairings; preferred height doesn’t correlate well with actual partner height, and pairings in which the man is taller only occur marginally more than would be expected by a random pairing process. Assortative mating for height exists, but it is weaker than you’d expect simply from enforcing the male-taller norm.

Why might this be? The pair formation process is complex and imperfect; you’re competing for a limited pool of mates with their own preferences and priorities, you probably won’t ever bump into your soulmate even if they were out there waiting for you, and there are numerous considerations to weigh.

It does however seem to be the case that short men tend to be more likely to remain single. Numerous explanations for why women seem to prefer taller men have been put forth. Perhaps ancestrally it assisted in protecting one’s kin through superior fighting ability or intimidation. To be able to afford allocating excess energy to developing taller stature may be an honest signal of fitness. Its association with higher social status or health may play a role. Since preferences seem at least somewhat malleable, it could also be partially due to social norms. It seems safe to say that the effect is at least partially an effect of height per se, as it survived the addition of education, earnings, and health to the model. Of course this effect was also quite trivial though, especially when contrasted with the extremity of much of the rhetoric we often hear. It’s certainly not the case as the tweet stated that 5’6” men have ‘zero prospects’. To be fair, one thing that may be missed here is that short men may go through more rejections. Tall women are also somewhat more likely to remain single, but perhaps less due to men’s preferences and more because they find it harder to find a tall enough man.

One interesting finding was that even this small effect wasn’t observed among 20-29s. The likely rejoinder from black pillers would be that tall men are having too much fun sleeping around and don’t want to be locked down yet. I’ve already demonstrated that height does not predict male short-term sexual behaviour, however. Considering height’s association with intelligence, it could be that taller people have slower ‘life history strategies’. Stulp et al. (2015) found that tall men and women were the latest to begin their relationships. Instead of being too busy ‘slaying’, they may be too busy working on their educations and establishing a career before investing in a relationship. They may also be more choosy with who they get with.

It was also not found that this effect has intensified over time, which you might have expected due to women’s economic empowerment allowing them to shift their priorities to other criteria, or due to the supposed game changing effect dating apps have had. Of course if you’re familiar with my previous explorations, you shouldn’t be surprised to see another way in which dating apps have had remarkably little impact on the dating landscape. Qualitatively, despite tentative evidence for taller men having more attractive partners, they didn’t seem to enjoy their relationships any better either.

References

Salska, I., Frederick, D. A., Pawlowski, B., Reilly, A. H., Laird, K. T., & Rudd, N. A. (2008). Conditional mate preferences: Factors influencing preferences for height. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.08.008

Swami, V., Furnham, A., Balakumar, N., Williams, C., Canaway, K., & Stanistreet, D. (2008). Factors influencing preferences for height: A replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.012

Courtiol, A., Raymond, M., Godelle, B., & Ferdy, J. (2010). MATE CHOICE AND HUMAN STATURE: HOMOGAMY AS a UNIFIED FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING MATING PREFERENCES. Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00985.x

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., & Pollet, T. V. (2013). Women want taller men more than men want shorter women. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(8), 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.019

Yancey, G., & Emerson, M. O. (2014). Does height matter? An examination of height preferences in Romantic coupling. Journal of Family Issues, 37(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x13519256

Lynn, M., & Shurgot, B. A. (1984). Responses to lonely hearts advertisements. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 10(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167284103002

De Sousa Campos, L., Otta, E., & De Oliveira Siqueira, J. (2002). Sex differences in mate selection strategies: Content analyses and responses to personal advertisements in Brazil. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(5), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(02)00099-5

Pawlowski, B. (2002). The impact of traits offered in personal advertisements on response rates. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(01)00092-7

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., Kurzban, R., & Verhulst, S. (2013). The height of choosiness: mutual mate choice for stature results in suboptimal pair formation for both sexes. Animal Behaviour, 86(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.038

Belot, M., & Francesconi, M. (2006). Can Anyone Be “the” One? Evidence on Mate Selection from Speed Dating. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.941111

Hitsch, G. J., Hortaçsu, A., & Ariely, D. (2010). What makes you click?—Mate preferences in online dating. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 8(4), 393–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-010-9088-6

Su, X., & Hu, H. (2019). Gender-specific preference in online dating. EPJ Data Science, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-019-0192-x

Courtiol, A., Picq, S., Godelle, B., Raymond, M., & Ferdy, J. (2010). From preferred to actual mate characteristics: the case of human body shape. PloS One, 5(9), e13010. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013010

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., Pollet, T. V., Nettle, D., & Verhulst, S. (2013). Are Human Mating Preferences with Respect to Height Reflected in Actual Pairings? PloS One, 8(1), e54186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054186

Sohn, K. (2015). The male-taller norm: Lack of evidence from a developing country. Homo, 66(4), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchb.2015.02.006

Tao, H.-L. (2016). Male-Taller and Male-Not-Too-Tall Norms in Taiwan: A New Methodological Approach. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704916671522

Stulp, G., Simons, M. J., Grasman, S., & Pollet, T. V. (2016). Assortative mating for human height: A meta‐analysis. American Journal of Human Biology, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22917

Sheppard, J. A., & Strathman, A. J. (1989). Attractiveness and height: The role of stature in dating preference, frequency of dating, and perceptions of attractiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15(4), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167289154014

Fu, H., & Goldman, N. (1996). Incorporating health into models of marriage choice: Demographic and sociological perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(3), 740–758. https://doi.org/10.2307/353733

Harper, Barry. (2000). Beauty, Stature and the Labour Market: A British Cohort Study. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 62. 771-800. 10.1111/1468-0084.0620s1771.

Murray J. E. (2000). Marital protection and marital selection: evidence from a historical-prospective sample of American men. Demography, 37(4), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2000.0010

Cawley, J., Joyner, K., & Sobal, J. (2006). Size Matters: The Influence of Adolescents’ Weight and Height on Dating and Sex. Rationality and Society, 18(1), 67-94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463106060153

Sunder M. (2006). Physical stature and intelligence as predictors of the timing of baby boomers' very first dates. Journal of biosocial science, 38(6), 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005027276

Hacker, J.. (2008). Economic, Demographic, and Anthropometric Correlates of First Marriage in the Mid-Nineteenth-Century United States. Social Science History. 32. 10.1215/01455532-2008-001.

Stulp, G., Pollet, T. V., Verhulst, S., & Buunk, A. P. (2012). A curvilinear effect of height on reproductive success in human males. Behavioral ecology and sociobiology, 66(3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-011-1283-2

Weitzman, A., & Conley, D. (2014). From assortative to ashortative coupling: men’s height, height heterogamy, and relationship dynamics in the United States. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20402

Sorjonen, Kimmo & Enquist, Magnus & Melin, Bo. (2017). Male height and marital status. Personality and Individual Differences. 104. 336-338. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.035.

Yamamura, E., & Tsutsui, Y. (2017). Comparing the role of the height of men and women in the marriage market. Economics and human biology, 26, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2017.02.006

Thompson, K., Koolman, X., & Portrait, F. (2021). Height and marital outcomes in the Netherlands, birth years 1841-1900. Economics and human biology, 41, 100970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100970

National Center for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

Blewett, L. A., Drew, J. A. R., King, M. L., Williams, K. C. W., Chen, A., Richards, S., & Westberry, M. (2023). IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 7.3 (Version 7.3) [Data set]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D070.V7.3

Buunk, A. P., Park, J. H., Zurriaga, R., Klavina, L., & Massar, K. (2008). Height predicts jealousy differently for men and women. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.11.006

Stulp, G., Buunk, A. P., & Pollet, T. V. (2013b). Women want taller men more than men want shorter women. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(8), 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.019

Sohn, K. (2016). Does a taller husband make his wife happier? Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.039

Feingold, A. (1982). Do Taller Men Have Prettier Girlfriends? Psychological Reports, 50(3), 810-810. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.50.3.810

Pawlowski, B., Boothroyd, L. G., Perrett, D. I., & Kluska, S. (2008). Is female attractiveness related to final reproductive success?. Collegium antropologicum, 32(2), 457–460.

Oreffice, S., & Quintana-Domeque, C. (2010). Anthropometry and socioeconomics among couples: evidence in the United States. Economics and human biology, 8(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2010.05.001

Tuomela, J., Kaprio, J., Sipilä, P. N., Silventoinen, K., Wang, X., Ollikainen, M., & Piirtola, M. (2019). Accuracy of self-reported anthropometric measures - Findings from the Finnish Twin Study. Obesity research & clinical practice, 13(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2019.10.006

Stulp, G., Barrett, L., Tropf, F. C., & Mills, M. (2015). Does natural selection favour taller stature among the tallest people on earth? Proceedings - Royal Society. Biological Sciences/Proceedings - Royal Society. Biological Sciences, 282(1806), 20150211. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.0211

I like the post thus far but please consider enabling TTS. I prefer passively listening as I do other things in general, it's more enjoyable. Thank you

https://support.substack.com/hc/en-us/articles/7265753724692-How-do-I-listen-to-a-Substack-post-

(Request form)

https://airtable.com/shr11c70LRWq9saOb

It’s quite though to read that short men like myself (5’8”) tend to be more single despite putting the effort . Looks like it’s time to embrace the black pill I guess