Have Dating Apps Really Ruined The Dating Landscape?

Challenging popular narratives around online dating

Key takeaways

Data on dating app outcomes show a high degree of gender parity regarding meeting, dating, have sex, and forming relationships. The distributions of unique dates are also very similar.

Men outnumber women on dating apps about 3:1. When adjusting for this imbalance, the median match rate for men and women on Tinder evens out, meaning the average woman isn’t matching with a bunch of chads.

Both men and women have a strong desirability skew, but the people who actually end up exchanging messages and going on dates probably tend to be quite close in terms of their within-gender desirability rank. This is less obvious on swipe apps because for efficiency reasons many men opt for a swipe first and ask questions later strategy.

Dating apps aren’t simply hook-up apps—relationships are a strong motivation for using them, at least as strong for men as is casual sex. This motive better predicts meeting up than a sexual motive, and committed relationships seem at least as common an outcome as a hook-up.

Dating app users might have more sex partners on average, but this is probably mostly the result of a selection effect whereby individuals higher in sociosexuality who are engaging in more casual sex to begin with are more likely to be using dating apps. There is some tentative evidence for dating apps leading to more sexual encounters—at least among those who are so inclined—but this effect is at best minimal, and of the minority of dating app users who’ve hooked up through one, most of them had only done so once. This also didn’t seem to be disrupting relationships.

A narrative once relegated to obscure incel forums has officially hit the mainstream, being disseminated through CNN, Real Time with Bill Maher, Breaking Points, and so on to millions of people. It has even begun to be promoted by prominent scholars such as Jonathan Haidt and make its way into academic journals (Blake & Brooks, 2023; Lindner, 2023; Larsen & Kennair, 2024).

Larsen & Kennair describe the situation thusly:

Sex differences in mate preferences empower women in short-term markets, giving them practically unlimited access to casual sex with higher-value men (Buss & Schmitt, 2011). Less restrained by monogamous mating morality—and given access to larger, more accessible short-term markets through technologies like Tinder—many women can serially date the small percentage of men whom they perceive to be the most attractive.

So what is the basis for this ever-pervasive meme? Basically, the observation that women receive much more attention and practice much more selectivity on online dating. This much is undeniable, though is extrapolating from this to an infinite conveyor belt of chads being delivered to every woman’s doorstep on-demand justified? There's no way this idea could be so widespread and taken seriously by seemingly intelligent people if it were completely unfounded, is there?

Actual outcomes

The argument tends to revolve around imbalanced swipe rates, but the truth is they offer little insight into how many men and women are actually matching, conversing, arranging a date, and then having anything meaningful come of it.

Luckily, there exists a good deal of data with the capacity to test this hypothesis, even if it has received little to no attention. The chadopoly hypothesis of course predicts that we should see more women than heterosexual men who have dated and had sex through dating apps. Are they really funneling 80% of the women to the top 20% of men as black pilled incel ‘Shoe0nHead’ asserts in the Breaking Points interview? Let’s cut to the chase and look at what the actual outcome data says.

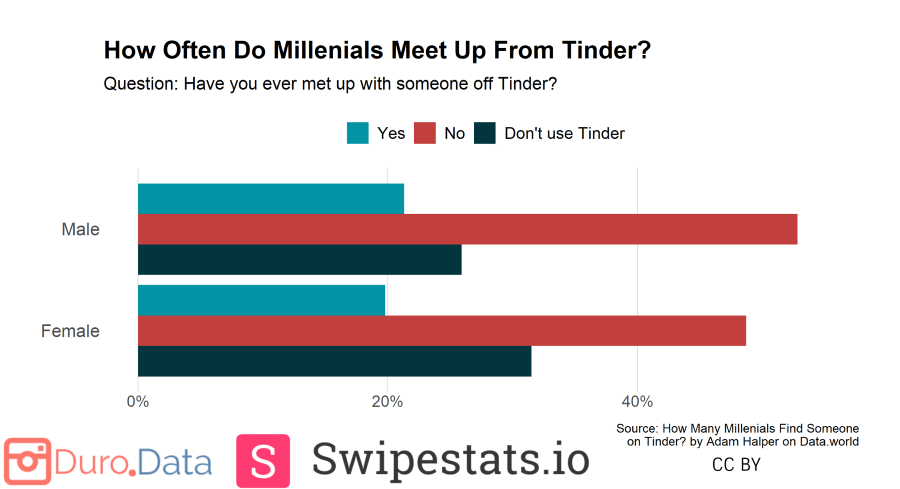

One of these is actually a chart found in the same article including the one we’ve all seen showing the average woman swiping right on only 5% of profiles on Tinder. It depicts the share of Millennials who’d met up with someone through Tinder before: about 20% of women and 21% of men.

A large nationally representative US survey, the National Survey of Family Growth, included in the 2017-19 survey the following question: “In the past 12 months, have you had sex with anyone you first met using a dating or “hookup” website or mobile app?”.

Among heterosexuals aged 18-35, 7.5% of men and 6% of women responded yes (not a statistically significant difference). We see that online dating facilitates sex a lot more for queer folks, likely due to having more incentive to turn to apps to expand their dating pool, and at least in the case of men, simply doing what many heterosexual men would be doing if they could.

Another survey, the American Perspectives Survey, in 2020 asked people if they’d used online dating, and if so whether they’d been on a date through it. Among heterosexuals aged 18-35, of the 52.4% of men and 39.1% of women had used online dating, 62.1% of men and 71.8% of women had been on a date through it, for 32.5% of men and 28.1% of women overall.

Another American Perspectives Survey conducted in 2022 found that among heterosexuals aged 18-35, of the 30.6% of men and 26.4% of women had used online dating, 65.3% of men and 76% of women had been on a date through it, for 20% of men and 20.8% of women overall.

Using the raw data provided by Blanc et al. (2023) which employed a large sample of Spaniards aged 18-35, I found that of the 43.1% of heterosexual men and 23.5% of heterosexual women who’d used a dating app, 41.8% of men and 54.4% of women had had vaginal or anal sex through it, for 18% of men and 12.7% of women overall.

According to a survey conducted by YouGov and BBC Newsbeat in 2018, that of the 49% of males and 41% of females between the ages of 16-34, 66% of males and 71% of females had never gone on a date through online dating, for 32.3% of males and 29.1% of females overall.

Males and females also had highly similar distributions of number of first dates through online dating in the past year, so it doesn’t seem like there’s a noticeably stronger skew within men either.

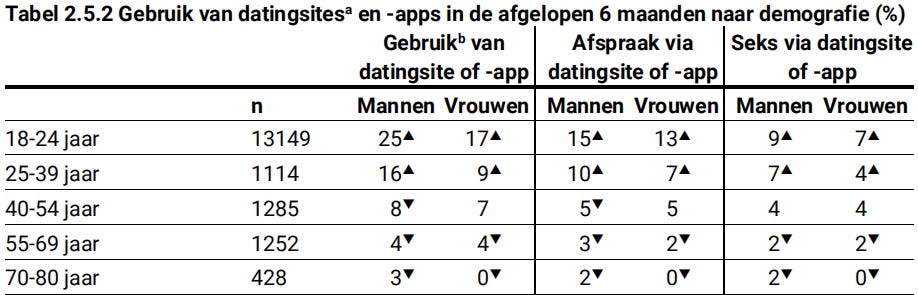

A representative Dutch survey was conducted in 2017. Of 4,934 men and 8,216 women between the ages of 18-24, 15% of men and 13% of women had been on a date through online dating in the past 6 months, and 9% of men and 7% of women had had sex through it. Of 427 men and 687 women between the ages of 25-39, 10% of men and 7% of women had been on a date through online dating in the past 6 months, and 7% of men and 4% of women had had sex through it. Since this included all sexual orientations, homosexual/bisexual men could help explain the discrepancies.

A Swiss national survey of young adults aged about 26 was conducted in 2017. Of 2,864 men and 2,746 women, 17.6% of men and 18.7% of women stated they'd ever had one date with someone met online, and 30.4% of men and 24% of women stated they had several times. Overall this comes out to 48% of men and 42.7% of women. 35.2% of men and 22.5% of women stated that they'd had sex with someone they met online before, with more men saying they do often.

A 2021 YouGov survey of 1,260 Americans found that 16% of men and 13% of women had been in one committed relationship through online dating, and 14% of men and 9% of women had been in more than one.

A 2022 YouGov survey of 3,900 Brits found that 17% of men and 19% of women had met someone in real life through a dating app.

Yu et al. (2022) analyzed data from the 2020 Chinese Private Life Survey. 19.3% of males and 17.2% of females aged 18-25 (N = 2,253) had hooked up with someone they met online.

Are dating apps facilitating ‘hook-up culture’?

Popular discourse surrounding dating apps tends to frame them as ‘hook-up apps’ which are contributing to the ‘hook-up culture’ we allegedly inhabit, at the expense of long-term relationship formation. Many an article has been written along these lines:

“I call it the Dating Apocalypse,” says a woman in New York, aged 29. As the polar ice caps melt and the earth churns through the Sixth Extinction, another unprecedented phenomenon is taking place, in the realm of sex. Hookup culture, which has been percolating for about a hundred years, has collided with dating apps, which have acted like a wayward meteor on the now dinosaur-like rituals of courtship.

Given that the majority of young adults haven’t met or had sex with anyone through dating apps, with only a small minority of heterosexuals having had sex with someone they first met online in the past year, this would seem to put a limit on how big its impact on sexual behaviour can have been, but it’s still be worth knowing the kind of behaviour they’re associated with.

Though is certainly research you can point to which appears to support this narrative, for instance showing dating app users reporting more sex partners, hook-ups, and STI diagnoses than non-users, with this effect being especially strong in more active users (Sawyer et al., 2018; Flesia et al., 2021; Mignault et al., 2022), or showing many young adults reporting knowledge of someone who’s used Tinder to meet extradyadic sex partners, or having engaged in infidelity through it themselves (Weiser et al., 2016).

However, we’re interested in establishing a causal connection, and research has also shown that dating app users tend to score higher in sociosexuality—or the willingness and desire to engage in uncommitted sexual relations (Botnen et al., 2018; Barrada & Castro, 2020; Barrada et al., 2021), higher in sexual permissiveness and need for sex (Shapiro et al., 2017; Sumter & Vandenbosch, 2018), higher in risk-taking propensity (Fowler & Both, 2020), higher in extraversion and openness to experience and lower in conscientiousness (Timmermans & De Caluwé, 2017; Fowler & Both, 2020), and higher in dark triad traits (Sevi, 2019). Sevi (2018) found higher health and safety risk taking propensity and lower sexual disgust sensitivity, but only among the female subsample, maybe due to the average male passing the threshold. Even just the fact that you won’t see a married couple who met at church when they were teenagers on Tinder (or at least so you’d hope) will cause some selection bias.

There are some mixed findings regarding some of these traits, for instance while one study finds that the Big Five and particularly openness is predictive while the Dark Triad isn’t (Castro & Barrada, 2020), another found the opposite (Freyth & Batinic, 2020), but the overall picture that emerges is that dating apps tend to select for people who are more short-term oriented on average. We therefore shouldn’t be surprised to observe that these same people tend to engage in more promiscuous behaviour.

One study found that after controlling for age, sex, and sociosexual desire, the association between length of dating app usage and lifetime casual sex partners vanished (Botnen et al., 2018). Another found that for both men and women dating app use and casual sex was mediated by a more risky sexual script (Tomaszewska & Schuster, 2020).

At the same time, app users don’t necessarily display a reduced long-term mating orientation (Barrada et al., 2021), so it’s not the case that dating app users are uninterested in relationships. Potarca et al. (2020) found that people in non-cohabiting couples formed through dating apps had greater interest in cohabitation than those meeting offline, and people in relationships formed through dating apps weren’t any less interested in marriage than those formed elsewhere. Moreover, women who met their partners online were more likely to desire and intend to have children in the near future.

It’s typically the case that casual sex and romantic relationships emerge as similarly strong motivators for men’s dating app usage, while women report a significantly lower casual sex motivation (Tyson et al., 2016; Sumter et al., 2017; Sevi et al., 2018; Sumter & Vandenbosch, 2018).

This reflects general patterns in mating orientation: while men are far more short-term oriented than women, women are at most marginally more long-term oriented than men (Schwarz et al., 2020).

So how does this pan out in regards to outcomes? In Sumter et al. (2017), of the six motivations, only the love motive significantly positively predicted going on a date through Tinder. The casual sex motive predicted having a one-night stand through Tinder, though this was not a very common outcome of dates—slightly less than 20% people had experienced a one-night stand compared to almost half having gone on a date.

Timmermans & Courtois (2018) found that of some half of the subjects who’d met a Tinder match, 23% had had through it at least one one-night stand, 31% a casual sexual relationship, and 27% a committed relationship. Since the mean for Tinder facilitated one-night stands was 0.43, we can deduce that most who’d had one had only had the one. Relationship motive predicted offline meetings, but interestingly not committed relationships. Sexual motive predicted one-night stands and casual sexual relationships on the other hand.

Harrison et al. (2022) found that dating app matches met in person correlated at .21 with the hook-up motive and .5 with the love motive. In a regression model including sensation seeking, love motive, hook-up motive, social desirability, and gender, only the love motive significantly predicted having met a dating app match in person. Similarly, Menon (2024) found that unlike the sexual motive, the love and socialization motives positively predicted going on Bumble dates.

Grøntvedt et al. (2020) found among Tinder users a match to meet up ratio of 57:1, a meet up to one-night stand ratio of 5.4:1, and a meet up to forming a long-term relationship ratio of 5.1:1. This would mean that it takes on average around 300 matches for either of these outcomes to occur. Of the 20% of users who’d had a one-night stand through Tinder, 13% had only had the one, 3% had two, and 4% had more than two. Another interesting finding was that how many one-night stands users had had outside of Tinder was only weakly positively correlated with Tinder one-night stands, and this correlation actually reversed after controlling for other factors.

While the research on this topic tends to be correlational, there are some studies which may offer some clues as to causality. Garga et al. (2021) found among a music festival-goer sample (who you’d expect to engage in more risk behaviours) that only 18% reported an increase in the number of sex partners since using dating apps.

Selterman et al. (2022) found no difference between dates initiated through dating apps or offline in felt attraction, perceptions of partners as sexy/hot, intelligent, or friendly, or likelihood of consuming alcohol or engaging in sexual activity.

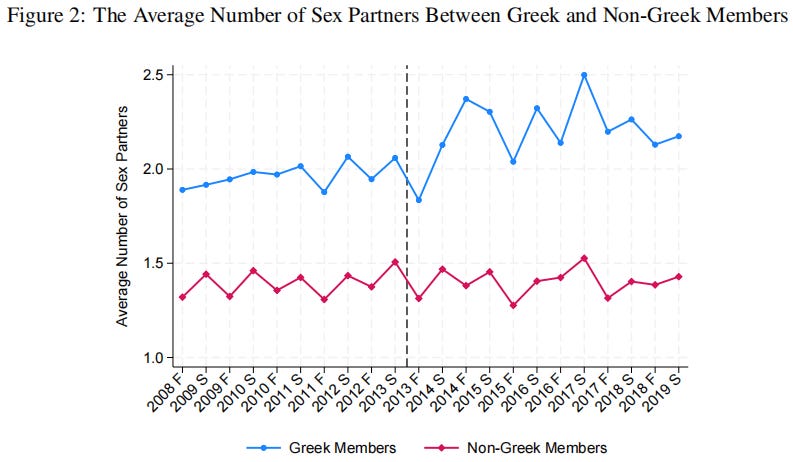

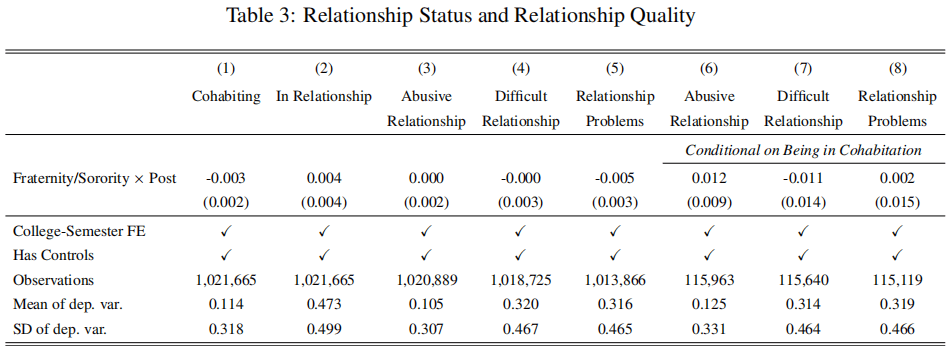

Buyukeren et al. (2022) analyzed data from the National College Health Assessment survey. Here we see the changes in average number of sex partners in the past year split by Greek (members of fraternities and sororities) and non-Greek undergrads. While there was no observable change among non-Greek students following the introduction of Tinder, Greek students appeared to show a minor increase in sex partners. This was interpreted as demonstrating a causal impact since Tinder’s launch strategy focused on Greek organizations.

This effect was nothing earth shattering however. Greek students had on average 0.22 more sex partners in the past year and were 3.1% more likely to have had sex in the past year, changes of less than 0.1 SD. It also didn’t seem to continue rising linearly along with the popularity of dating apps.

There were increases in the incidence of Greek students being diagnosed or treated for chlamydia in the past year and ever being tested for HIV of 0.6% and 1.6%, respectively, or 0.04 SDs. Of course the increase in chlamydia diagnoses could also potentially reflect an increase in testing or unprotected sex which isn’t necessarily connected to an increase in promiscuity.

While these effects seem to lend credence to the idea that dating apps are associated with a small increase in promiscuity—at least within the subpopulation already more inclined toward it, a negative effect on relationship status or quality wasn’t detected, so it doesn’t seem like it’s the result of people foregoing relationships in favour of hook-ups or ‘situationships’.

Interestingly, mental health if anything improved somewhat for Greek students, and especially for women. This includes eating disorders. This goes against the notion that dating apps are contributing to a mental health crisis for instance through causing body image issues or women being lured into sex with the pretense of a relationship before being callously discarded by bad chads.

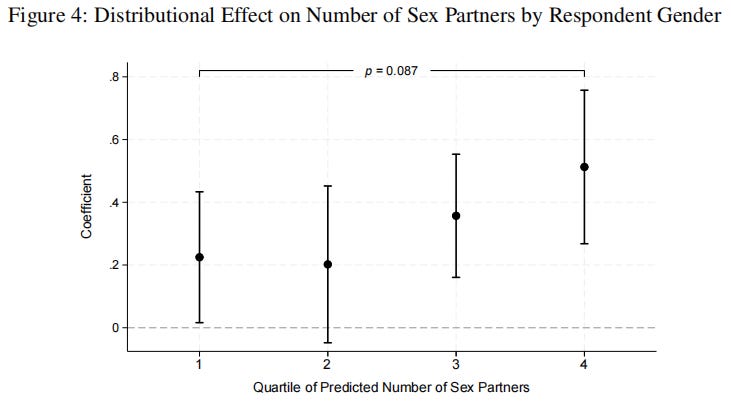

They also tested whether there was heterogeneity in the effect on sex partners by how many sex partners they were ‘predicted’ to have, and found that there was a slightly larger effect among the upper quartile of men. This still fails to support the Chadopoly theory however, as all quartiles seemed to ‘benefit’ to a degree. The Chadopoly theory on the other hand would predict the top quartile gaining partners at the expense of the others, and especially the bottom one. There wasn’t a significant effect here between the top and bottom quartile, either1.

There doesn’t appear to be compelling evidence for an increasing ‘consolidation of mating’ if looking at representative surveys or STD rates:

Some more data relevant to the ‘hook-up culture’ narrative for good measure: Monitoring the Future doesn’t show a significant increase in 21-30 men or women reporting three or more sex partners in the past year:

What is everyone getting wrong?

Many will find this highly counter-intuitive. If women are being so much more selective, then how come we don’t see any disparity in outcomes?

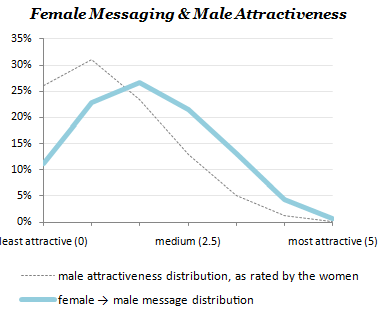

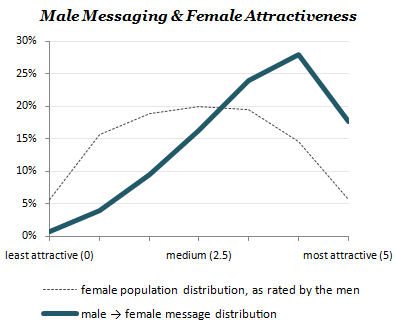

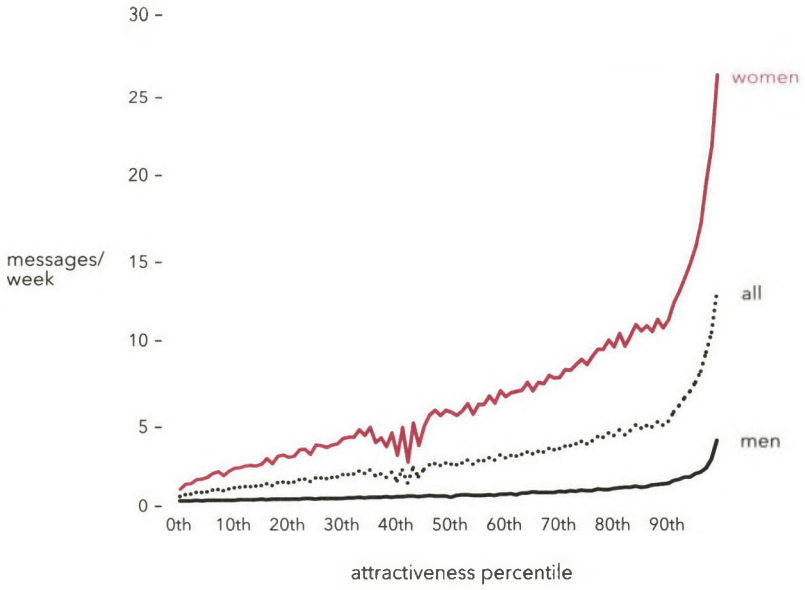

Let’s begin with the infamous OKCupid data, which has been the source of much indignation over the years. I’m hardly the first one to address this, but since the ratings graph is still routinely posted out of context as evidence for the online dating-facilitated chadopoly narrative (including in one of the papers mentioned), let us briefly ‘look at what they do, not what they say’.

In a blogpost by OKCupid co-founder Christian Rudder, the attractiveness rating distributions were compared to the message distributions. Both women and men’s messages were delivered disproportionately to the higher rated members. If anything, relative to how many men and women were rated low, the low rated men fared better than the women—but this could potentially be explained by a tendency for less attractive women to initiate more conversations due to being less able to sit back and wait for men to reach out to them.

This has also been visualized in his book ‘Dataclysm’:

We also see that the average woman received more messages than even the most popular men—perhaps not too surprising considering that even in the ‘real world’ dates are initiated by men 90% of the time.

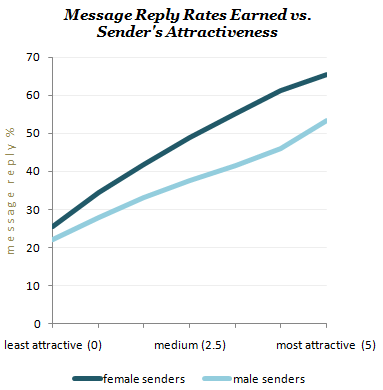

A common retort is that the apparent similarity in the effect of attractiveness is simply a product of this. However, a graph showing reply rates by the sender’s attractiveness also shows similar patterns, while the chadopoly narrative might predict a curve like the one seen in the previous graph.

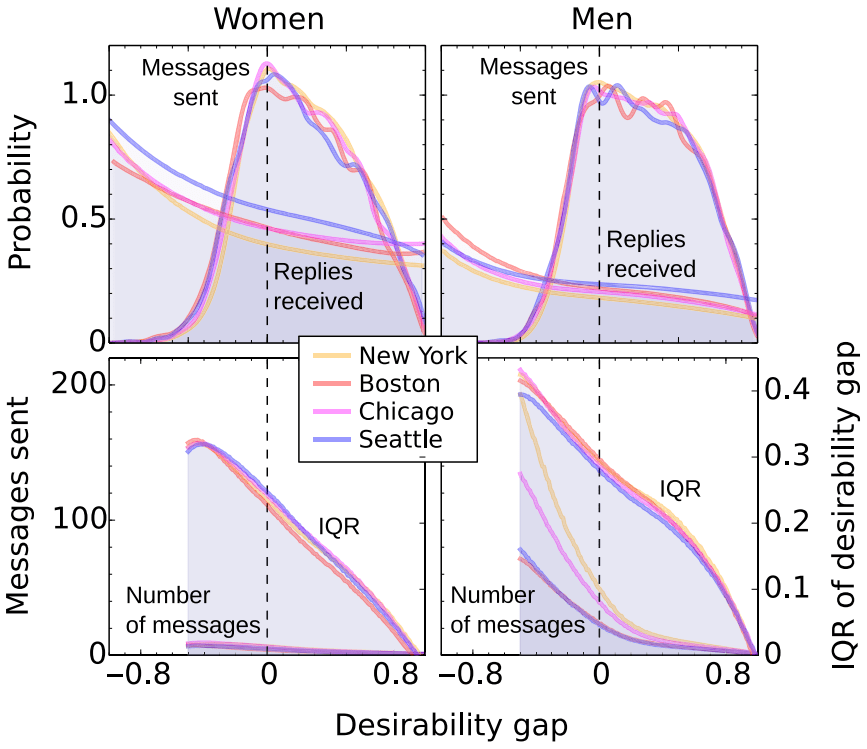

A number of studies have yielded similar findings. Bruch & Newman (2018) examined messaging activity across a one-month period on an online dating service. Users’ desirability was measured by a combination of the number of messages they received and how many their senders did.

The graph below shows messaging behaviour as a function of the ‘desirability gap’. The most common targets for both genders in terms of the mode were of roughly equal desirability to themselves, though on average both shoot above their league to a degree. Again, as with OKCupid we see men sending a lot more and receiving less, but also a comparable effect of desirability on replies received for each gender.

Kreager et al. (2014) found in addition to similar patterns that the desirability gap narrowed with the more messages that were exchanged, so that most resulting pairings would’ve been quite homogamous.

It seems that at least on online dating services in which one is able to send a message without a matching system acting as a barrier, we see that both men and women are quite discriminating in their decision-making, with a comparable hierarchy of desirability within each gender. Of course men’s role as initiators is retained in the online world, and for each level of desirability women are receiving more attention, but the notion that women can easily date up a lot just by hopping on an online dating service seems questionable.

An oft-cited example of the male desirability skew comes from a since deleted Hinge report. The male data was reported in two of the papers I cited in the intro, yet the female data wasn’t. Same with the incel wiki.

While there might be substantial ‘inequality’ between the genders, the inequality within each gender isn’t that far apart: the top 10% of male profiles received 58% of the likes, while the top 10% of female profiles received 46%2.

This is despite the well-established gender imbalance in online dating. A Pew survey from 2022 (dataset) shows 19% of young men and 7% of young women were currently using online dating, for a ratio of roughly 3:1. 62% of young men and 46% of young women had ever used it before (including current users).

Returning to the source for the Tinder swipe chart, it also showed a median match rate of about 1 a day for men and 2.75 for women. We should probably adjust for the gender ratio of users at any one time though, as with more people to match with a higher number of per capita matches is a given. Since this lines up with the gender ratio of current users, the match rate actually evens out.

To the extent that their swipes disproportionately target ‘the same 5% of guys’, it doesn’t look like they’re reciprocated much, as otherwise the median woman would have proportionally more matches than the median guy after adjusting for the gender ratio. Either they’re not saving their attention for the same top men nearly as much as is typically inferred from the swipe rate, or these men aren’t nearly as willing to reach down in attractiveness as is typically assumed. Since the same source also showed the median woman matching with 36% of the profiles they swiped right on, to a significant degree it must be the former.

While the swipe ratio is more imbalanced than you’d expect based on the gender ratio imbalance, we probably shouldn’t expect it to be perfectly calibrated. Not just because women practice more selectivity in general, but because of a feedback loop whereby as competition for women’s attention increases, women are incentivized to apply more selectivity as a higher proportion of their swipes will result in a match, until a substantial number of men decide it’s more efficient to adopt a strategy of ‘shoot first and ask questions later’.

In line with this, Tyson et al. (2016) found that 35% of men reported frequently ‘casually liking most profiles’, while no women did. Also, while men send the bulk of initial messages, a higher percentage of them receive replies compared to those sent by women (Zhang et al., 2016), which hints at some portion of men filtering out undesired matches after the fact.

We’ve also seen that, unsurprisingly, a lot more men report casual sex as a strong motivation for dating app usage. If everyone were only swiping on profiles they’d consider for a long-term relationship, we might see some convergence.

Along with the skewed gender ratio, only a fraction of matches resulting in conversations, a fraction of conversations in the exchange of contact details (19% of mutual conversations involved the sharing of a phone number in the previous study), a fraction of these leading to dates, and a fraction of these leading to anything, this means that swipes alone tell us very little.

Why don’t women like online dating?

One question which often arises is why dating apps are so male-dominated. They also report a more negative sentiment toward and experience using online dating than do men (see also: Pew), and while men and women both tend to say they’d prefer meeting a romantic partner without using online dating, more women than men do.

To the extent that they are or at least are perceived to be ‘hook-up apps’, this will no doubt turn off more women than men. Bars and clubs have similar problems attracting female patrons. Even if the chances are infinitesimal, many men will just be swiping away when they can for a chance at winning the jackpot.

As stated earlier, men remain the more active party in courtship the majority of the time. When you’re being frequently pursued already, you’ll naturally feel less incentive to sign up to an app. In a similar vein, many men report ‘ease of communication’ as a motivating factor. Dating apps are appealing for men who suffer from a lot of anxiety approaching and interacting with women, and provide a buffer against much of the sting of rejection.

Risk aversion could play a role. They may have heard a horror story which even if is highly unlikely to occur to them influenced their perception enough to matter.

Some may have had negative experiences such as being ‘pump and dumped’, though of course we’ve established that the narrative that a small minority of men are doing this to a large percentage of women is untenable.

A long-standing contention of evolutionary psychology is that men are more visual than women. Some have argued that while this is true in the case of stated preferences, we see similar value placed on looks in people’s behaviour. Whatever the case, it’s probably true that women at least have wider set of criteria which may be difficult to properly assess through a dating app profile.

Being so highly in demand may sound good on paper, but may also lead to choice overload. It may be hard to sympathize with this problem from the other side, and you might argue that this isn’t as bad as receiving no matches at all, but it’s a well-studied phenomenon in psychology. People are more likely to purchase items and be satisfied with their decisions when they’re presented with a modest rather than extensive selection. This has also been studied in the context of dating apps. Having a higher number of partner options bred a ‘rejection mind-set’, increased dissatisfaction with pictures, and increased pessimism about finding a partner. Many women might simply delete the app soon after downloading it as they find the overwhelming attention to be mentally draining. This could conceivably be another self-reinforcing cycle leading to a more skewed gender ratio with time.

Conclusion

The leap from women on average swiping right on 5% of men to women all hooking up or ‘serially dating’ 5% of men never made much sense. One thing that has been observed to precipitate a rise in casual sex is a female-skewed gender ratio, as men have more leverage to set the terms of engagement when they're in higher demand. This clearly isn't the case here however.

You could argue that it happens more subtly, such that dark triad chads lead women on by feigning interest in a relationship before callously pumping and dumping their ‘victims’, who repeatedly fall into the same trap as they refuse to settle for their ‘looksmatch’. This probably overstates not just the amount of ‘chads’ who are promiscuous bad boys, but also how many women are susceptible to their deception. There’s good reason to think they possess effective defenses against dishonest signals of commitment. Sexual regret may also function to avoid repeatedly making the same mistake in the future.

The truth is, there wasn’t anything stopping this from happening before the advent of phone apps, especially if it really were the natural dynamic which arose in the absence of ‘enforced monogamy’. Not a single phone was needed in the formation of any gorilla harems for instance. They would at most accentuate it by providing a more efficient and secretive means of facilitation. As is the case now however, sex partner distributions were similar for each gender, with a minority of both partaking in anything approaching promiscuity.

It’s become a truism that ‘most people are meeting online now’, though this is based on a tiny sample who met during covid. The 2017 data point showing 40% of heterosexuals meeting online was also based on a pretty low sample size of 60, and the follow-up survey showed the percentage drop to 20-25% in 2018-19. The real figure is likely in the range of 25-30%. The majority of sexual encounters are probably still occurring offline too. In a sample of Norwegians aged 18-30, of people who’d had at least one new sex partner in the past year, about 30% had met their last or second to last partner online. Dating apps also seem to be losing their luster among the youth, with Match Group’s shares and paying users on the decline. It could be that they are shifting to other online mediums to meet people such as social media though.

What is clearly true about dating apps is that they are clearly not a very effective tool for meeting women, and we don’t need any more ‘chadfish’ experiments to tell us that yes, being more attractive helps one’s chances quite a bit. It makes sense on an emotional level why this narrative resonates with a lot of men, especially if you aren't in many social situations and have limited connections or alternative avenues. It’s not hard to see why it would lead to much frustration and be degrading to one’s self-esteem. Neither this nor the popularity of the narrative speaks to its validity however. You could argue that it shows how women are more actively desired than men, but there’s no reason to believe that this gap was produced by dating apps.

With all this in mind, it seems unlikely that dating apps have radically altered the dating landscape or are the proximate cause of many men’s dating woes. If it has had an effect, it will be a lot more subtle than chadopolies or rampant promiscuity. You might argue that the more superficial format isn’t conducive to enduring relationships as people rush into relationships without the time or information to adequately evaluate compatibility or other traits that are important in a relationship, and lack a shared social network. A Swiss study however found that people in relationships beginning on dating apps didn’t differ from those who met offline when it came to relationship or life satisfaction (maybe contradicting the earlier mentioned choice overload theory to an extent), nor marital or fertility intentions. A longitudinal study found that people who had met online didn’t predict shorter lived relationships from 2009 to 2015 and if anything it predicted faster transitions to marriage, though another study found a higher rate of divorce during the first three years for people meeting online.

Whatever the impact, it doesn’t seem revolutionary. Ironically, this was also the conclusion of Rosenfeld, the lead author behind the study showing the big spike in people meeting online:

For heterosexuals, the impact of phone dating apps on their dating lives has clearly been overstated in the popular press. Tinder is not, as Sales (2015) suggested, a sign of “the dating apocalypse.” Most heterosexuals are stably married, and there is no evidence that phone dating apps or any other modern technology have undermined or will undermine relationship stability in the USA.

References

Blake, K. R., & Brooks, R. C. (2023). Societies should not ignore their incel problem. Trends in cognitive sciences, 27(2), 111–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.11.007

Lindner, M. (2023). The Sense in Senseless Violence: male reproductive strategy and the modern sexual marketplace as contributors to violent extremism. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 9(3), 217–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-023-00219-w

Larsen, M., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2024). Enough with the incels! A literary cry for help from female insings (involuntary single).Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000349

van Lisdonk, Jantine & Nikkelen, Sanne. (2018). Seksuele oriëntatie (chapter in Dutch monitor Sexual Health in the Netherlands 2017).

Barrense-Dias Y, Akre C, Berchtold A, Leeners B, Morselli D, Suris J-C. (2018). Sexual health and behavior of young people in Switzerland. Lausanne, Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive, 2018 (Raisons de santé 291). http://dx.doi.org/10.16908/issn.1660-7104/291

Yu, J., Luo, W., & Xie, Y. (2022). Sexuality in China: A review and new findings. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 8(3), 293-329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X221114599

Sawyer, A. N., Smith, E. R., & Benotsch, E. G. (2017). Dating application use and sexual risk behavior among young adults. Sexuality Research & Social Policy/Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(2), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0297-6

Flesia, L., Fietta, V., Foresta, C., & Monaro, M. (2021). “What are you looking for?” Investigating the association between dating app use and sexual risk behaviors. Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 100405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100405

Mignault, L., Vaillancourt-Morel, M., Ramos, B., Brassard, A., & Daspe, M. (2022). Is swiping right risky? Dating app use, sexual satisfaction, and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2078804

Botnen, E. O., Bendixen, M., Grøntvedt, T. V., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2018). Individual differences in sociosexuality predict picture-based mobile dating app use. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.021

Barrada, J. R., & Castro, Á. (2020). Tinder Users: Sociodemographic, psychological, and psychosexual characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health/International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218047

Barrada, J. R., Castro, Á., Del Río, E. F., & Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J. (2021). Do young dating app users and non-users differ in mating orientations? PloS One, 16(2), e0246350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246350

Shapiro, G. K., Tatar, O., Sutton, A., Fisher, W., Naz, A., Perez, S., & Rosberger, Z. (2017). Correlates of Tinder use and risky sexual behaviors in young adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(12), 727–734. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0279

Sumter, S. R., & Vandenbosch, L. (2018). Dating gone mobile: Demographic and personality-based correlates of using smartphone-based dating applications among emerging adults. New Media & Society, 21(3), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818804773

Fowler, S. A., & Both, L. E. (2020). The role of personality and risk-taking on Tinder use. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100067

Timmermans, E., & De Caluwé, E. (2017). To Tinder or not to Tinder, that’s the question: An individual differences perspective to Tinder use and motives. Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.026

Sevi, B. (2019). The dark side of Tinder. Journal of Individual Differences, 40(4), 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000297

Sevi, B. (2018). Brief report: Tinder users are risk takers and have low sexual disgust sensitivity. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(1), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-018-0170-8

Castro, Á., Barrada, J. R., Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J., & Fernández-Del-Río, E. (2020). Profiling dating apps users: Sociodemographic and personality characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health/International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103653

Freyth, L., & Batinic, B. (2021). How bright and dark personality traits predict dating app behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110316

Botnen, E. O., Bendixen, M., Grøntvedt, T. V., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2018b). Individual differences in sociosexuality predict picture-based mobile dating app use. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.021

Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2019). Comparing Sexuality-Related Cognitions, sexual behavior, and acceptance of sexual coercion in Dating App Users and Non-Users. Sexuality Research & Social Policy/Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00397-x

Barrada, J. R., Castro, Á., Del Río, E. F., & Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J. (2021b). Do young dating app users and non-users differ in mating orientations? PloS One, 16(2), e0246350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246350

Potarca, G. (2020). The demography of swiping right. An overview of couples who met through dating apps in Switzerland. PloS One, 15(12), e0243733. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243733

Tyson, G., Perta, V. C., Haddadi, H., & Seto, M. C. (2016). A first look at user activity on tinder. 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM). https://doi.org/10.1109/asonam.2016.7752275

Sumter, S. R., Vandenbosch, L., & Ligtenberg, L. (2017). Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009

Sevi, B., Aral, T., & Eskenazi, T. (2018). Exploring the hook-up app: Low sexual disgust and high sociosexuality predict motivation to use Tinder for casual sex. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.053

Sumter, S. R., & Vandenbosch, L. (2018b). Dating gone mobile: Demographic and personality-based correlates of using smartphone-based dating applications among emerging adults. New Media & Society, 21(3), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818804773

Schwarz, S., Klümper, L., & Hassebrauck, M. (2019). Are sex differences in mating preferences really “Overrated”? The effects of sex and relationship orientation on Long-Term and Short-Term mate preferences. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 6(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00223-y

Timmermans, E., & Courtois, C. (2018). From swiping to casual sex and/or committed relationships: Exploring the experiences of Tinder users. The Information Society, 34(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1414093

Harrison, M. G., McAnulty, R. D., & Canevello, A. (2022). College Students’ Motives for In-Person Meetings with Dating Application Matches. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 25(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0031

Menon, D. (2024). The Bumble motivations framework- exploring a dating App’s uses by emerging adults in India. Heliyon, 10(3), e24819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24819

Grøntvedt, T. V., Bendixen, M., Botnen, E. O., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2019). Hook, line and sinker: Do Tinder matches and meet ups lead to One-Night stands? Evolutionary Psychological Science, 6(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00222-z

Garga, S., Thomas, M. T., Bhatia, A., Sullivan, A., John-Leader, F., & Pit, S. W. (2021). Motivations, dating app relationships, unintended consequences and change in sexual behaviour in dating app users at an Australian music festival. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00493-5

Selterman, D., & Gideon, S. (2022). Experiences of romantic attraction are similar across dating apps and offline dates in young adults. Journal of Social Psychology Research, 145–163. https://doi.org/10.37256/jspr.1220221542

Buyukeren, B., Makarin, A., & Xiong, H. (2022). The impact of dating apps on young adults: Evidence from Tinder. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4240140

Kendrick, S., & Kepple, N. J. (2022). Scripting Sex in Courtship: Predicting genital contact in date outcomes. Sexuality & Culture, 26(3), 1190–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09938-2

Kreager, D. A., Cavanagh, S. E., Yen, J., & Yu, M. (2014). “Where have all the good men gone?” Gendered interactions in online dating. Journal of Marriage and the Family/Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12072

Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., Jain, V., Karjaluoto, H., Kefi, H., Krishen, A. S., Kumar, V., Rahman, M. M., Raman, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., Rowley, J., Salo, J., Tran, G. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.995

Pronk, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019). A rejection Mind-Set: Choice overload in online dating. Social Psychological & Personality Science, 11(3), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619866189

Moss, J. H., & Maner, J. K. (2015). Biased sex ratios influence fundamental aspects of human mating. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215612744

Buss, D. M. (2017). Sexual conflict in human mating. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417695559

Bakkelund, Thomas. (2019). Nettdatingstudien. Rapporterer unge voksne forskjellig seksualatferd med partnere de har møtt på internett sammenliknet med partnere de har møtt på tradisjonelle møtesteder? [Master thesis, University of Tromsø]. UiT Munin. https://munin.uit.no/handle/10037/15719

Bearman, P. S., Moody, J., & Stovel, K. (2004). Chains of Affection: the structure of adolescent romantic and sexual networks. American Journal of Sociology, 110(1), 44–91. https://doi.org/10.1086/386272

Rosenfield, M. (2017). Marriage, choice, and couplehood in the age of the internet. Sociological Science, 4, 490–510. https://doi.org/10.15195/v4.a20

Rosenfeld, Michael. (2018). Are Tinder and Dating Apps Changing Dating and Mating in the USA?. 10.1007/978-3-319-95540-7_6.

Despite this, they state that ‘Inequality in dating outcomes increased among male students but not among female students’.

There is also simply the fact that some users are more active than others, or have been users for longer than others. I don’t know if this was corrected for at all.

I admit that this is good analysis and proves the ‘Chad’ theory at least partially wrong.

But the path to showing that dating apps are bad for dating relies more on empathy than the gini coefficients alone. The *process* of getting left swiped and ghosted over and over again is murder to any self confidence or enjoyment, which, yes, is a worse experience than being spoiled for choice.

It’s also clear that the apps aren’t doing a good job at sorting. They’re probably trying to to falsely put hot girls in front of too many guys to get them to pay for the premium version.

Also, hypothesis of mine: I suspect one reason women don’t like apps is because they’re text based, and so don’t convey the body language / spontaneity / tone of voice so important to charisma

Hang on a second, people aged 18-35 isn't the actual baseline population. The actual baseline population is people who are "available" for online dating. This causes artificially low percentages on some of these statistics, e.g. "Proportion who had sex in the past year with someone first met through a dating app or website". Obviously everyone who was in a long-term relationship for that entire year is off the table (except cheaters).

Also, 18% straight men vs 12% straight women having sex on a dating app does lend credence to the notion that there's a disproportionate subset of the women on the dating apps that are having sex with multiple men. I'm aware that there's going to be survey error on both of those data points so it's not as clear as it'd otherwise be, but if you take it at surface level, that's a 1.5:1 ratio. If it's not down to an extremely tiny minority of women having sex with a lot of different men, that ratio would have a fairly large impact on the social dynamics.

The problem isn't so much the dating apps themselves, it's the near-total elimination of every other method of meeting people and arranging first dates. (No more church dates due to the decline of religion, dating at universities becoming increasingly fraught with peril, and dating in the workplace being almost completely banned.) As a result, "dating app culture" (for lack of a better term) has become the dominant means for meeting people, and that selects for a particular crowd - and leaves everyone else out in the cold, as there is no longer a broadly socially approved means of trying to initiate a relationship outside of it.