Do Looks Really Buy Happiness and Confidence?

'Pretty privilege' doesn't seem to translate to meaningful psychological benefits

‘Black pillers’ believe they hold the key to understanding how society truly operates—that they’ve uncovered a controversial truth too dark for blue-pilled normie consumption. Take for instance this YouTube video on ‘why looks are everything in life’, featuring everyone’s favourite recurring characters and the words ‘BRUTAL TRUTH’ emblazoned on the thumbnail:

One commenter exclaims:

THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTION! WHY IS SOCIETY AFRAID TO RECOGNIZE THAT APPEARANCE IS VERY IMPORTANT?!

As the title implies, the prevailing belief in the ‘black pill’ community is that all of one’s problems in life can be reduced to not being pretty enough. Many posts on their forums are some variation of this edgy screed:

Reminder, YOU are an ugly inferior subhuman that's life unworthy of life. You have NO friends because of your LOOKS. You have NO girlfriend because of your LOOKS. You struggle to socialize because of your LOOKS. You were bullied as a teen or child in a school environment because of your LOOKS. You don't pass job interviews because of your LOOKS. You don't upload yourself frequently onto social media (Instagram) because of your LOOKS. You never turned on your camera for Zoom/Microsoft Meetings because of your LOOKS. The only difference between a slayer and a sexless virgin is the LOOKS. If you switched bodies with a pretty boy right now and had the same personality, you would never deviate from Lookism ever again.

The general idea that ‘looks matter’ isn’t anything new, of course; ‘Beauty is the promise of happiness’, 19th-century French writer Stendhal famously mused. Nevertheless, alongside other ideas associated with the ‘black pill’, the ‘looks are everything in life’ narrative seems to be gaining traction.

With the rise of social media and dating apps, society may be perceived by many as being more superficial than ever, with hot people living it up more than ever, so these sentiments will likely only grow going forward. Historically, issues such as the internalization of ‘unrealistic’ beauty ideals have been mostly associated with women, but the whole ‘looksmaxxing’ trend could signify that they are increasingly affecting men.

An important question arises: to what extent are physical appearance and psychology intertwined? Do beautiful people develop an inner sense of confidence and wellbeing from living in a paradise world of their own, or is people's envy misplaced?

Potential mechanisms linking looks and psychology

There are several mechanisms which could potentially explain an association between looks and psychological traits:

‘Lookism’: The basic idea is that due to the halo effect attractive people are treated better and granted more social opportunities, and so they develop confidence and ‘good personalities’. Conversely, ugly people due to negative social feedback and rejection withdraw and are stunted in their social-emotional development.

Calibration: In a similar vein, people may calibrate their personality to their attractiveness depending on its contingent effectiveness; for example, extraversion may be a more effective ‘strategy’ when you’re attractive and thus have more ‘bargaining power’.

Genetic covariance: It may be the case that physical attractiveness and ‘good’ psychological traits covary at the genetic level. One possible causal mechanism is ‘cross-trait assortative mating’, whereby people exchange one desirable trait (e.g., attractiveness) for other desirable traits when selecting partners. Another is that higher mutational load can lead to deficiencies in both physical and mental development.

Malnutrition: This could do the same.

Reverse causality: It’s also possible that an association could be caused not by attractiveness improving people’s confidence and psychological wellbeing, but rather these leading to more self-enhancement, while depressed or asocial people tend to live a more sedentary lifestyle and may feel less motivated to enhance or maintain their appearance. Their poor mental state could also come through in their expressions and body language.

For all their talk about genetics, incels/black pillers tend to subscribe to a ‘blank slate’ model of human nature. In their view, the differences between people’s minds are just another product of ‘lookism’ and its interaction with one’s psychosocial developmental trajectory.

They even go so far as to apply this to neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism.

Let’s put this popular narrative to the test.

Does personality follow from looks?

‘Confidence’ is a word that comes up a lot (‘just be confident bro’, etc.). Shrauger & Schohn (1995) developed a self-confidence measure called the Personal Evaluation Inventory, which included the domains of speaking before people, romantic relationships, athletics, social interactions, physical appearance, and academic performance. Self-confidence was defined as ‘the subjective appraisal of one’s own capabilities and/or performance in a given context’. General self-confidence correlated with other psychological measures in ways you might expect: positively with extraversion and self-esteem, negatively with neuroticism, anxiety, and depression. To test the narrative that variation in ‘confidence’ is determined by ‘lookism’, we should examine how these and related traits interact (or don’t) with attractiveness.

Beginning with Noles et al. (1985), as expected, depressed subjects were less satisfied with their overall appearance, body parts, viewed themselves as less attractive, and generally evaluated their physical appearance in a less favourable manner than non-depressed subjects. However, these negative self-appraisals turned out to not be based in reality, as they perceived themselves as less attractive than outside observers did, while non-depressed subjects tended to distort their body image in the opposite direction. In other words, it was all in their heads.

Rapee & Abbott (2006) extended these findings to social anxiety. Even after controlling for depression levels, the socially phobic group rated their attractiveness significantly lower than the control group rated theirs, but the same difference wasn’t found in the case of observer-rated attractiveness. In the case of speech performance, the discrepancy between self- and observer-ratings was again larger for the socially phobic group, but this time observer ratings were also significantly (though only slightly) lower for them than the control group.

These results are consistent with the idea that negatively biased self-perceptions underlie the expectation of negative evaluations from others. They are not consistent, however, with the lookism theory which posits that social phobia stems from negative social feedback on the basis of looks.

Kenealy et al. (1991) examined data from a longitudinal study investigating the social and psychological impacts of malocclusion and the effectiveness of orthodontic treatment. The subjects were some 1,000 children who were aged 11-12 at the onset of the study in 1981. Consistent with previous results, children’s facial and dental attractiveness as rated by a panel of judges was unrelated to their self-esteem, while self-perceived attractiveness was somewhat related.

In a follow-up interview twenty years later, Kenealy et al. (2007) found that subjects who had received orthodontic treatment didn’t fare any better psychologically in adulthood after adjusting for the general trend of self-esteem increasing over time which was observed. Additionally, forgoing treatment despite a prior need for it didn’t lead to worse mental health outcomes down the road, even though those who did undergo it saw improvements in dental health and attractiveness. Part of the justification for early orthodontic treatment is the promise of long-term psychological benefits, but based on this analysis they conclude that this is not a valid justification after all.

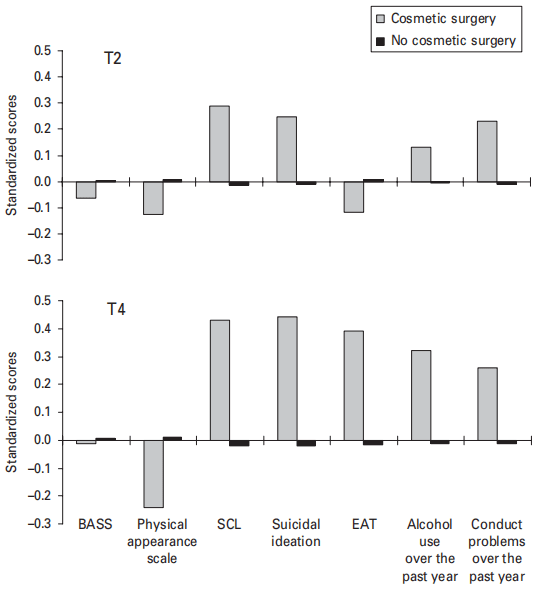

This isn’t just a one-off finding, either; von Soest et al. (2012) examined a sample of some 1,600 adolescent females and found that, among the 5% who underwent cosmetic surgery over a 13-year period, they ended up more relatively high than those who didn’t in depression and anxiety symptoms, eating problems, and alcohol consumption than they were beforehand.

In a sample of 365 young adolescents (Webb et al., 2017), peer-reported attractiveness failed to correlate with the self-reported measures of appearance rejection sensitivity (anxiety over social rejection on the basis of appearance) at T1 and T2, peer appearance conversations, peer appearance teasing, peer appearance pressure, parent appearance teasing, family appearance pressure, parent appearance attitudes, media pressure, and general rejection sensitivity. The only variables it correlated with are weakly with internalization of media ideals and BMI (negatively).

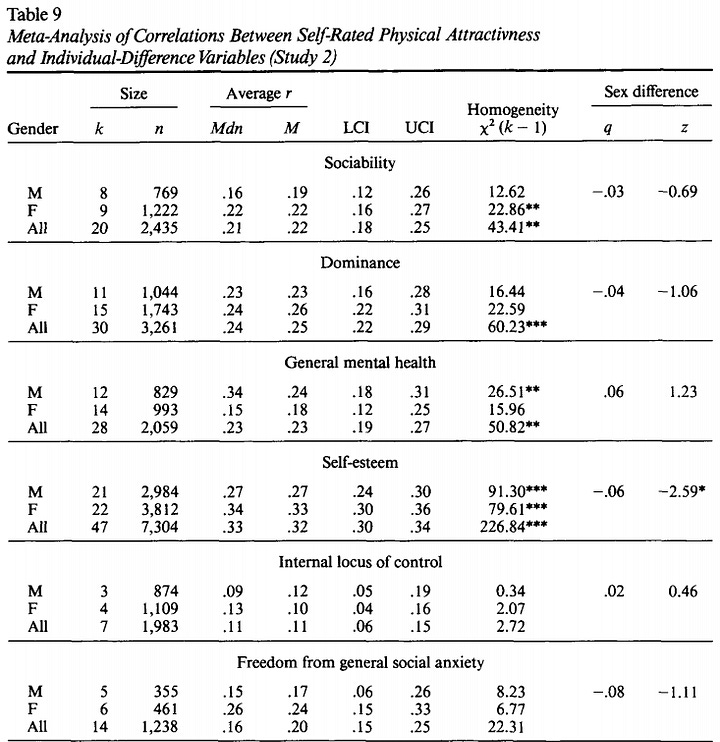

A meta-analysis by Feingold (1992) sought to determine if stereotypes about good looking people were accurate. In the second part of the study, studies involving correlations between self- and other-rated attractiveness and a variety of psychological traits were analyzed.

Below are the results for some pertinent traits: sociability and dominance (comparable to extraversion), general mental health (generally reverse-coded anxiety or neuroticism), self-esteem, internal locus of control (the degree to which people believe they’re in control of their lives), and freedom from general social anxiety. For self-rated attractiveness, the correlations tended to hover around .25, whereas those for observer-rated attractiveness were only barely above 0. Only one significant sex difference emerged, with women’s self-esteem being correlated more with attractiveness, but it was still a very weak correlation in the case of observer-rated attractiveness.

A slightly stronger effect of observer-rated attractiveness was found for social skills (r = .23), but since this was generally measured by a judge assessing a subject’s behaviour during an opposite-sex interaction, these assessments would likely be confounded by the halo effect.

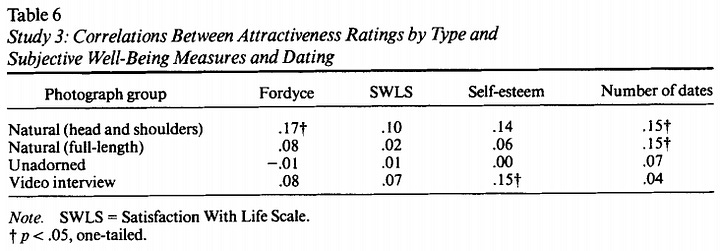

Diener et al. (1995), across three studies, found only very small and inconsistent associations between observer-rated attractiveness in the form of frontal and profile photos and video footage with satisfaction with life, happiness, and self-esteem. In study 1, It correlated with informant-rated self-confidence at .06, and with informant-rated social skills at .17. In the second study, the top and bottom quartiles in attractiveness were compared, and they were found not to differ in happiness or satisfaction with life. In the third, two groups representing the bottom 26% and top 45% of a happiness scale didn’t significantly differ in attractiveness. From a total of 34 correlations between looks and satisfaction with other domains such as family, grades, health, and career, the only one which reached statistical significance was satisfaction with one’s romantic life at .18-.23 (depending on how attractiveness was rated).

McGovern et al. (1996) analyzed a sample of 1,100 female twins with an average age of 30 and found no association whatsoever between attractiveness and three measures of depression; one for lifetime incidence and one for incidence in the preceding year of neurovegetative symptoms (fatigue, insomnia, dysregulated eating), and one of cognitive dimensions (hopelessness, worry, lack of pleasure) of depression in the past month.

More recent studies have also failed to show meaningful associations. Borráz-León et al. (2021) found in a sample of 358 college students an average correlation of -.11 between observer-rated attractiveness and somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostiliy, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and general psychopathology index, with only half reaching statistical significance. Facial fluctuating asymmetry only significantly correlated with 1/10. Costa & Maestripieri (2023) found in a sample of 231 college students a small positive effect of observer-rated attractiveness on self-esteem, and small negative effects on anxiety and having a negative attitude towards the past, but no effect was found for locus of control, social status, any big-five traits, past-positive, present-hedonistic, present-fatalistic, or future time perspective. Using the raw data provided from Sanders et al. (2022) study 3, with a bit over 300 subjects, in a regression on self-esteem controlling for age, ethnicity, gender, SES, and sexual orientation, observer-rated attractiveness didn’t have a significant effect (β = 0.02), though self-rated attractiveness had a large effect (β = 0.63). Observer-rated attractiveness had a small effect on extraversion (β = 0.16), but not on neuroticism, meaning of life, satisfaction with life, or affect.

I also did a quick analysis on the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, which began in 1957. Most of the participants’ senior yearbook photos were able to be collected and rated by 6 men and 6 women between 2001-08. Below is how these ratings correlated with some pertinent psychological traits in a follow-up survey when participants would’ve been in their early 50s. Correlations for extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, psychological wellbeing1, and depression symptoms were on average around .04.

In case you need a visual representation of how uncorrelated this is:

A regression analysis of the General Social Survey data which included looks ratings2 (2016, 2018, 2022) controlling for age, sex, ethnicity, education, household income, and religious attendance, revealed a standardized effect of 0.06 for looks on happiness. Household income and religious attendance had slightly larger effects. I also tested for interaction effects of age and sex with looks, as well as a quadratic effect, but none found anything (results not shown).

I also ran some regressions on the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Wave IV dataset with sex, race, education, and date of birth as controls. Basically, the effect sizes were in line with the ones we’ve seen so far: .08 for the extraversion composite I created; .06 for feeling as good as other people in the past week; −.02 for feeling depressed in the past week; −.06 for treated worse in everyday life; and so on.

I could cite another few dozen studies or conduct a series of meta-analyses, but I trust that this has painted a clear enough picture.

The nail in the coffin

Although the prior analyses don’t leave much room for looks meaningfully shaping people’s psychosocial developmental trajectory, proper longitudinal analysis can provide an even more robust test of the theory.

In a study by Cole et al. (1997), peer, teacher, and parent reports of physical attractiveness of 617 third and sixth graders failed to predict a change in self-reported depression 6 months later. A further study by Cole et al. (1998) shed light on the directionality of the association between negative self-appraisals and depression/low self-esteem, revealing that depression was a precursor to self-underestimation rather than the reverse.

A longitudinal study of 230 adolescents aged 13-15 which were surveyed annually over a 5 year span found no effect of attractiveness or BMI on the development trajectory of self-esteem (Mares et al., 2010). In this study, there was actually a negative effect of attractiveness on older adolescents’ self-esteem at baseline.

A longitudinal study of 528 adolescents aged on average 11.2 at T1 and 14.8 at T4 (Magson et al., 2023) showed moderate correlations between life satisfaction, social anxiety, depression, and eating pathology and subjective (self-rated) attractiveness at each time point. In contrast, the correlations with objective attractiveness were extremely weak, with an average effect size of .04 and only 4/16 reaching statistical significance.

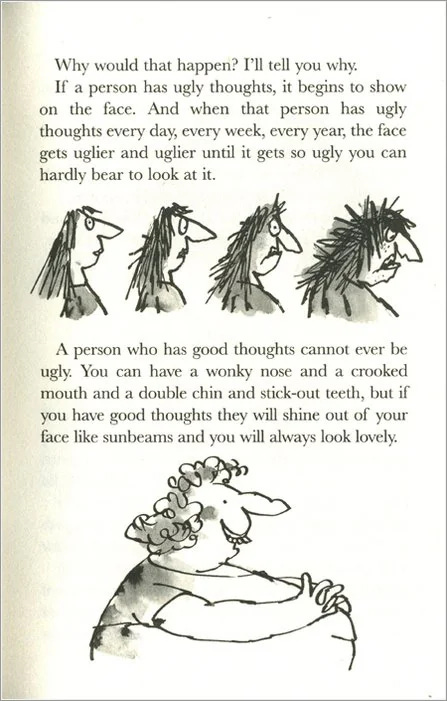

What’s particularly interesting about this study is that it actually provides empirical support for the above quote that ‘If a person has ugly thoughts, it begins to show on the face’, as corny as it may sound. Neither changes in subjective nor objective attractiveness over the years predicted later changes in internalizing symptoms, but on the other hand changes in internalizing symptoms not only predicted changes in subjective attractiveness, but even to an extent objective attractiveness. Therefore, the observed directionality is actually the opposite of that predicted by the lookism narrative, providing evidence for reverse causality. This stage of life, marked by the onset of puberty, is where you’d arguably expect looks to be the most socially salient, too.

Some more hints of reverse causality

Brown et al. (1988) found support for their hypothesis that people higher in self-esteem engage in more direct forms of self-enhancement, as it’s congruent with their positive self-image, while those lower in self-esteem are concerned with maintaining a consistent negative self-image, and may doubt their ability to live up to a more positive external image, so instead seek to self-enhance through more indirect means such as associating themselves with more successful people. Taylor et al. (2003) found that high self-enhancers had lower cardiovascular responses to stress, more rapid cardiovascular recovery, and lower baseline cortisol levels, which is consistent with the prior hypothesis, but not so much with the theory that self-enhancers are neurotics who seek to suppress negative information about themselves.

As can be seen in the tables below from Diener et al. (1995), there was a slightly higher correlation with psychological variables for the natural/adorned appearance conditions (which left their hair, cosmetics, and jewelry untouched) they arrived in, implying that even of these small correlations, they may in fact be mediated by self-enhancement motivation.

This was what a study by Meier et al. (2010) found: the relationships between extraversion and agreeableness with attractiveness were no longer significant after controlling for how well-groomed subjects appeared.

Do good looks = good health?

Nedelec & Beaver (2014) analyzed Add Health Wave IV data of some 15,000 respondents aged 24-32. Of the 13 individual health items, correlations ranged from −.01 to −.06, and general self-reported health correlated at .13, number of sick days at -.03, diseases at −.07, and neuropsychological disorders at −.05. If attractiveness functions as an honest signal of underlying fitness, it appears to be a remarkably inefficient one. Kalick et al. (1998) found that attractiveness ‘blinded’ people to the actual health of faces when rating their health, and argued that while it may have initially served as an honest signal, ‘deceptive’ displays came to dominate as there wasn’t enough of an incentive to evolve adaptations for detecting honest ones.

Foo et al. (2017) found no association between facial attractiveness and immune function, oxidative stress, or semen quality, Cai et al. (2019) found no association between facial attractiveness, dimorphism, averageness, or colouration and scores on three different health questionnaires or immune function, Borráz-León et al. (2021) found no association between facial attractiveness or fluctuating asymmetry and minor ailments (or between attractiveness and fluctuating asymmetry for that matter, which actually isn’t too unusual a finding—it may only really come into play when you look like a Picasso painting), and Pátková et al. (2022) found no association between facial attractiveness and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the Sanders et al. (2022) study 3 data I found no effect of observer-rated attractiveness on self-reported health. Mengelkoch et al. (2022) found some effects of facial attractiveness on some measures of immune function, however. Strangely, one of them showed a positive effect for men but a negative effect for women.

Given how small the effect sizes were in the Add Health study though, I guess it’s not terribly surprising to see these null results, as you’d need thousands of subjects to consistently detect these effects (though in the large WLS dataset Fieder & Huber failed to find a significant association between looks and genome-wide heterozygosity after correcting for multiple testing, and even before this it explained some 0.15% of the variance). If there were a strong relationship between looks and health, it might raise the question as to why we don’t also see a stronger relationship between looks and mental health considering physical and mental health are at least moderately correlated, but it looks like we don’t have to worry about that.

Possible reasons for the absence of a meaningful connection

Exaggerated benefits: This is certainly true to some extent. I’m not sure exactly how much of the difference in happiness between single and partnered people is actually caused by people being in a relationship (though I’m sure some of it is), but a ‘sub-5’ doesn’t have a much lower chance of being in a relationship regardless. When it comes to ‘slaying’—or sleeping around a lot—contrary to black pill assumptions this has very little to do with physical morphology, and even if it did higher partner counts aren’t associated with higher happiness anyway, even for men.

Black pillers also attribute their lacking social life to looks; however observer-rated attractiveness correlated with number of same-sex friends at only r = .08 in the Feingold meta-analysis. In the Add Health Wave IV data, I found an effect of β = 0.03 for men’s looks and number of close friends. To put this into perspective, for extraversion it was β = 0.28. In the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, attractiveness correlated with ‘times gotten together with friends in the past month’ at r = .03 in the 1975 survey. When you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense to believe that looks is a major barrier to socializing. The ‘Chadopoly’ meme is at least internally consistent in the case of intersexual dynamics, but is he also stealing away your looksmatched friends? What’s stopping you from befriending Chad yourself then? Even assuming friendship is largely based on looks (there is some evidence for matching at least), ugly people could always simply befriend each other if they were left out of the cool kids’ club; after all, it’s rare that you’re the only ugly kid around.

Hawley et al. (2007) found among 153 children that while attractiveness as rated by teachers correlated with teacher-assessed social skills, social prominence, and positive peer regard, this wasn't the case when going by independent raters of attractiveness. The teacher's familiarity with the students may therefore have confounded the association.

While the methodology seems questionable in many cases (using self-perceptions of attractiveness or having peers nominate both attractive and victimized or accepted students, etc.), there are some studies evidence for less attractive adolescents being rejected and victimized more—but the effect sizes are small. In Rosen et al. (2011), the association between teacher-reported victimization and anxious or withdrawn depression was also very small (and nonsignificant). If the effect of attractiveness on being bullied is small, and the effect of being bullied on psychological maladjustment is also small, then the indirect pathway linking attractiveness to psychological maladjustment through bullying will be very small.

Genes: An analysis of a twin study by Haysom et al. (2015) found similar heritability estimates for extraversion (.55 for men and .47 for women) and for facial attractiveness (.64 and .4). They also failed to detect a significant relationship between the genetic variation underlying facial attractiveness and variance in extraversion, which is a mark against the ‘facultative calibration’ or ‘reactive heritability’ model of personality.

It would be a mistake to presume that the unexplained variance must be explained by environmental causes, however. None of the remaining variance in extraversion was explained by shared environment; it was all unique to individuals, which includes measurement error. One study by Riemann & Kandler (2010) considered the variance shared by self- and peer reports. Genes ended up explaining on average 81% of the variance in big-five traits.

Clearly this high heritability can’t be a result of twins developing similar personalities due to looking the same. It appears then that contrary to what is implied by ‘black pillers’ (they will often make statements such as ‘it’s genes, not personality’, and in general their usage of the term implies a juxtaposition with nonphysical characteristics) genes are far from synonymous with ‘physical characteristics’.

Hedonic adaptation: Even if something may hurt or please us in the moment, we tend to inevitably return to a happiness set-point.

Subjectivity: The high reliability of attractiveness ratings across different groups, including cross-cultural comparisons, has been widely celebrated, but at the same time there is substantial variation between individual perceivers. This will mean that treatment on the basis of looks will also vary depending on the perceiver, attenuating any relationship between looks and general outcomes.

Double-edged sword: We hear a lot about the benefits, but there may also be situational drawbacks. The halo effect might create high expectations that beautiful people find it difficult to live up to. If they fail to, people may even begin to dislike them or see them as rude. Also, it’s not only positive attributes which are applied more to beautiful people; they may also be perceived as more vain. Beautiful people may sometimes become targets of jealousy and derogation from others due to being seen as competition. They may become overwhelmed by too much unwanted attention, etc.

How much it matters depends on one’s goals: Another finding by Diener et al. was that among those who stated that attractiveness was highly relevant to their goals, the correlations between attractiveness and satisfaction with life and happiness (r = .23, r = .14) was a bit higher than among those for whom it wasn’t (r = .1, -.02). The goal relevance of attractiveness was also only very weakly associated with observer-ratings of attractiveness (r = .11).

First impressions don’t always last: The people who beautiful people spend time around the most won’t need to rely on first impressions as much, and looks will take a lesser role in their interactions.

Conclusion

It appears that the adage that money can’t buy happiness is at least as true for looks. Despite this, this belief is widespread, even in the psychological literature. Since it seems intuitively correct and to logically follow from the ‘what is beautiful is good’ bias, I guess people just assume that there is a meaningful relationship between looks and psychological traits without giving it much further thought. Feingold’s meta-analysis is often cited as evidence of this relationship, when ironically the whole point of the paper was that good looking people aren’t how we think (this is the title of the paper in fact).

A study using the WLS dataset was featured in a QOVES video, with the implication being that looks have a strong impact, despite—like I showed—the effect being trivial at best. Failing to mention the magnitude of effects is a common issue in the reporting of scientific findings that has the potential to lead people to make ill-informed decisions:

Participants who viewed interventions with unreported effect magnitudes were more likely to endorse interventions compared with those who viewed interventions with small effects and were just as likely to endorse interventions as those who viewed interventions with large effects, suggesting a practical significance bias. When effect magnitudes were reported, participants on average adjusted their evaluations accordingly. (Michal & Shah, 2024).

Pretty much everything in the world correlates with everything else to some extent, it’s just a matter of gathering enough data. The question must then be: are these practically significant correlations? At a certain point there’s no meaningful distinction between ‘a very small effect’ and ‘no effect’. I don’t know what the justification would be for taking such negligible effects seriously. Even the most astute observer likely wouldn’t ever be able to pick up on them in their day to day life (even if they think they do due to cognitive biases).

Part of the large focus on looks’ benefits, even when in cases like this it turns out to be more fiction than fact, could be because people feel like it shouldn’t exist. People find inequality especially unjust if they see it as arising from immutable characteristics. People seem to feel less discomfort regarding inequality in outcomes that they see as arising from cognitive or personality variation, perhaps due to the notion that there is more agency involved in these contexts. This may also explain many people’s readiness to chalk their issues up to physical shortcomings, imagined or otherwise.

Now, to be fair, there is no shortage of studies you can point to showing how attractive people do indeed tend to enjoy preferential treatment in professional, social, romantic, and even legal settings. Again, we could argue over the precise magnitude of these advantages, but regardless, what good are these advantages if they don’t lead to positive psychological outcomes?

Our self-perception may be less influenced by external feedback than typically thought. If someone is comfortable in their own skin, devaluing feedback might tend to roll off their back, while a more neurotic person might obsess over it where there isn’t any. Confident people will believe they're hot even when they're not, while highly anxious people will believe they’re ‘subhuman’ even when they look normal (though of course by black pill standards, anything below ‘Chad’ is ‘subhuman’).

The only other reasonable explanation I can think of is that the halo and horn effects have simply been heavily overstated.

Overall, it seems like if you’re depressed or anxious, it’s unlikely that your physical appearance is to blame, and all the ‘looksmaxxing’ in the world won’t change the underlying psychological maladjustment driving these insecurities.

There is some evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy having a small benefit (though some respond better than others, the effect size will be larger for responders), and some issues may naturally lessen as you mellow out with age.

I could offer some generic mental health advice (which I should probably start following myself before doing so) such as exercise, meditate, eat better, touch grass, suntan your nuts, but unfortunately you won’t find the silver bullet here.

To a large extent, it might be that we have just replaced one ‘black pill’ with another.

References

Shrauger, J. S., & Schohn, M. (1995). Self-confidence in college students: Conceptualization, measurement, and behavioral implications. Assessment, 2(3), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191195002003006

Noles, S. W., Cash, T. F., & Winstead, B. A. (1985). Body image, physical attractiveness, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.1.88

Rapee, R. M., & Abbott, M. J. (2006). Mental representation of observable attributes in people with social phobia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.01.001

Kenealy, P., Gleeson, K., Frude, N., & Shaw, W. (1991). The importance of the individual in the "causal" relationship between attractiveness and self-esteem. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 1(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450010108

Kenealy, P. M., Kingdon, A., Richmond, S., & Shaw, W. C. (2007). The Cardiff dental study: a 20-year critical evaluation of the psychological health gain from orthodontic treatment. British journal of health psychology, 12(Pt 1), 17–49. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910706X96896

von Soest, T., Kvalem, I. L., & Wichstrøm, L. (2012). Predictors of cosmetic surgery and its effects on psychological factors and mental health: a population-based follow-up study among Norwegian females. Psychological medicine, 42(3), 617–626. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001267

Webb, H. J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Waters, A. M., Farrell, L. J., Nesdale, D., & Downey, G. (2017). "Pretty Pressure" From Peers, Parents, and the Media: A Longitudinal Study of Appearance-Based Rejection Sensitivity. Journal of research on adolescence : the official journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 27(4), 718–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12310

Feingold, A. (1992). Good-looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 304–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.304

Diener, E., Wolsic, B., & Fujita, F. (1995). Physical attractiveness and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.120

McGovern, R. J., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (1996). The independence of physical attractiveness and symptoms of depression in a female twin population. The Journal of psychology, 130(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1996.9915002

Borráz-León, J. I., Rantala, M. J., Luoto, S., Krams, I. A., Contreras-Garduño, J., Krama, T., & Cerda-Molina, A. L. (2021). Self-perceived facial attractiveness, fluctuating asymmetry, and minor ailments predict mental health outcomes. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 7(4), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-021-00172-6

Costa, M., & Maestripieri, D. (2023). Physical and psychosocial correlates of facial attractiveness. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000331

Sanders, C. A., Jenkins, A. T., & King, L. A. (2022). Pretty, meaningful lives: physical attractiveness and experienced and perceived meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(6), 978–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2155222

Hamermesh, D. S., & Abrevaya, J. (2013). Beauty is the promise of happiness? European Economic Review, 64, 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2013.09.005

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., & Powers, B. (1997). A competency-based model of child depression: a longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 38(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. G., Seroczynski, A. D., & Hoffman, K. (1998). Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: a longitudinal study. Journal of abnormal psychology, 107(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.481

Mares, S. H., de Leeuw, R. N., Scholte, R. H., & Engels, R. C. (2010). Facial attractiveness and self-esteem in adolescence. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology : the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 39(5), 627–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.501292

Magson, N. R., Oar, E. L., Fardouly, J., Rapee, R. M., Freeman, J. Y. A., Richardson, C. E., & Johnco, C. J. (2023). Examining the Prospective Bidirectional Associations between Subjective and Objective Attractiveness and Adolescent Internalizing Symptoms and Life Satisfaction. Journal of youth and adolescence, 52(2), 370–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01700-7

Brown, J. D., Collins, R. L., & Schmidt, G. W. (1988). Self-esteem and direct versus indirect forms of self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(3), 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.3.445

Taylor, S. E., Lerner, J. S., Sherman, D. K., Sage, R. M., & McDowell, N. K. (2003). Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological profiles?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(4), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.605

Meier, B. P., Robinson, M. D., Carter, M. S., & Hinsz, V. B. (2010). Are sociable people more beautiful? A zero-acquaintance analysis of agreeableness, extraversion, and attractiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(2), 293–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.02.002

Nedelec, J. L., & Beaver, K. M. (2014). Physical attractiveness as a phenotypic marker of health: An assessment using a nationally representative sample of American adults. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(6), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.06.004

Kalick, S. M., Zebrowitz, L. A., Langlois, J. H., & Johnson, R. M. (1998). Does human facial attractiveness honestly advertise health? Longitudinal data on an evolutionary question. Psychological Science, 9(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00002

Foo, Y. Z., Simmons, L. W., & Rhodes, G. (2017). Predictors of facial attractiveness and health in humans. Scientific reports, 7, 39731. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39731

Cai, Z., Hahn, A. C., Zhang, W., Holzleitner, I. J., Lee, A. J., DeBruine, L. M., & Jones, B. C. (2019). No evidence that facial attractiveness, femininity, averageness, or coloration are cues to susceptibility to infectious illnesses in a university sample of young adult women. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(2), 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.10.002

Pátková, Ž., Schwambergová, D., Třebická Fialová, J., Třebický, V., Stella, D., Kleisner, K., & Havlíček, J. (2022). Attractive and healthy-looking male faces do not show higher immunoreactivity. Scientific reports, 12(1), 18432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22866-x

Mengelkoch, S., Gassen, J., Prokosch, M. L., Boehm, G. W., & Hill, S. E. (2022). More than just a pretty face? The relationship between immune function and perceived facial attractiveness. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 289(1969), 20212476. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.2476

Hawley, P. H. (2007). Social dominance in childhood and adolescence: Why social competence and aggression may go hand in hand. In P. H. Hawley, T. D. Little, & P. C. Rodkin (Eds.), Aggression and adaptation: The bright side to bad behavior (pp. 1–29). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Rosen, L. H., Underwood, M. K., & Beron, K. J. (2011). Peer Victimization as a Mediator of the Relation between Facial Attractiveness and Internalizing Problems. Merrill-Palmer quarterly (Wayne State University. Press), 57(3), 319–347. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2011.0016

Haysom, H. J., Mitchem, D. G., Lee, A. J., Wright, M. J., Martin, N. G., Keller, M. C., & Zietsch, B. P. (2015). A test of the facultative calibration/reactive heritability model of extraversion. Evolution and human behavior : official journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, 36(5), 414–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.03.002

Riemann, R., & Kandler, C. (2010). Construct validation using multitrait-multimethod-twin data: The case of a general factor of personality. European Journal of Personality, 24(3), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.760

Michal, A. L., & Shah, P. (2024). A Practical Significance Bias in Laypeople's Evaluation of Scientific Findings. Psychological science, 35(4), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976241231506

This includes an autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance subscale.

The looks ratings in the GSS and Add Health surveys were made after an interview, which could introduce a confounding effect if the interviewer’s overall perception of the participant is influenced by their confidence or positive vibes. On the other hand, ratings made by a single person will be a bit less reliable, so any measurement error caused by this may cancel it out.

Fascinating stuff. I think this is probably your best piece as of yet because good looks mean nothing if their outcomes don’t increase what actually matters: happiness/life satisfaction in the limited time we have on earth.

On another note, even if we are replacing one ‘blackpill’ for another, gene editing for psychological maladjustments could be feasible within the next few decades through technologies like CRISPR and the rise of AI medical technology which can already modify genes related to physical conditions and certain inherited diseases.

Everything you put out basically just says to the majority "don't worry guys all these maladjusted cretins are garbage, they believe total bullshit and are seething brainlets" and basically you change the black pill from the admittedly false 'loads of men are struggling against some global chad pyramid' to 'if you are struggling with these issues you are a tiny minority and basically aren't worth caring about'