Just don't be extremely short

Height's impact on partnering seems confined to the extreme left tail. Why is it so overhyped?

Height and relationships: just don’t be a turbomanlet

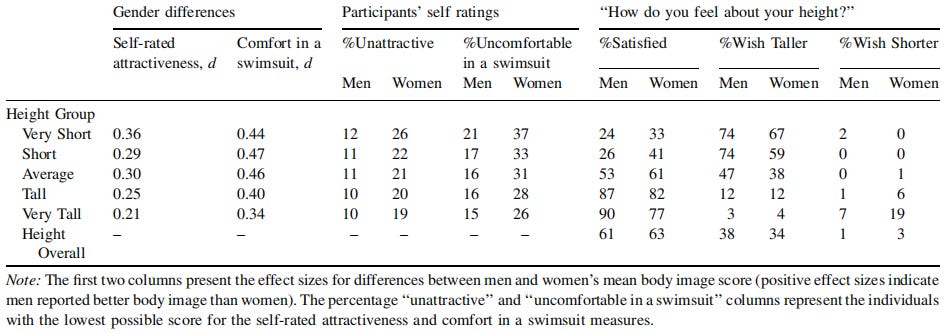

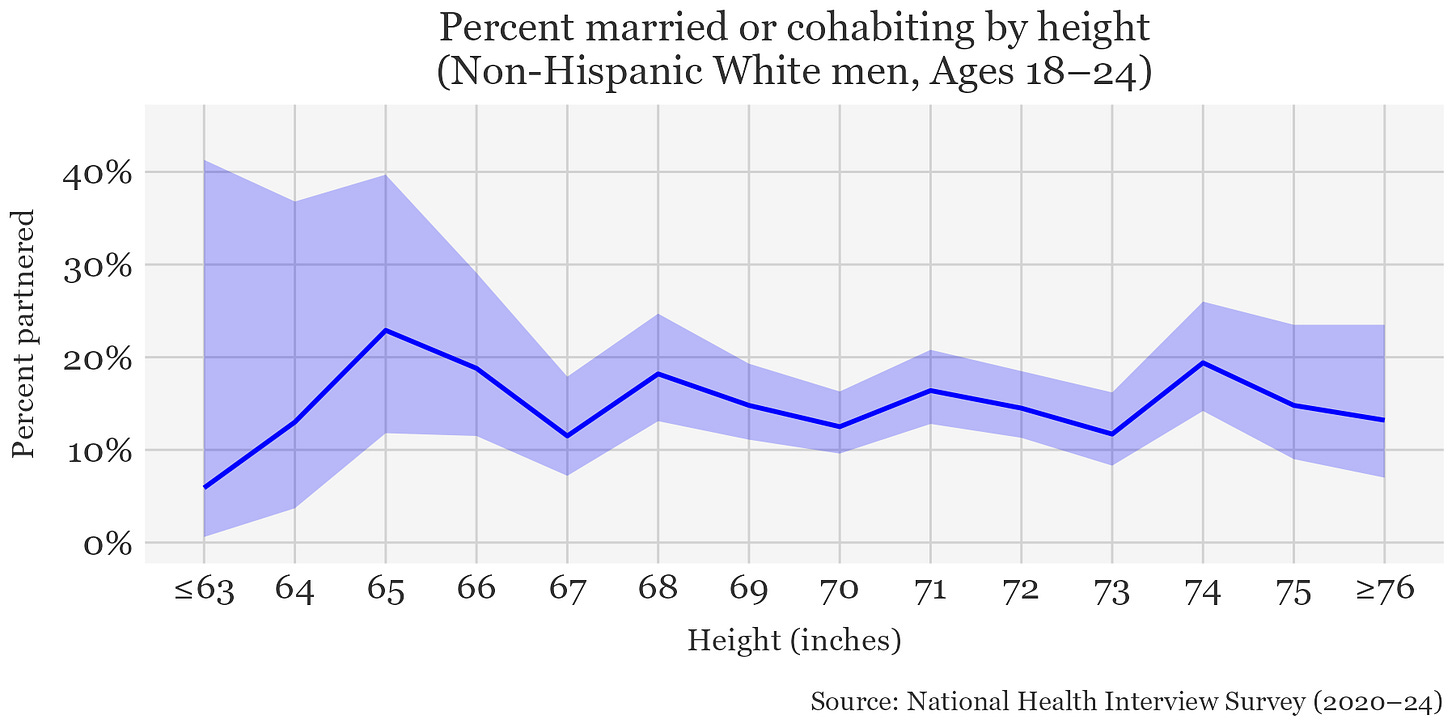

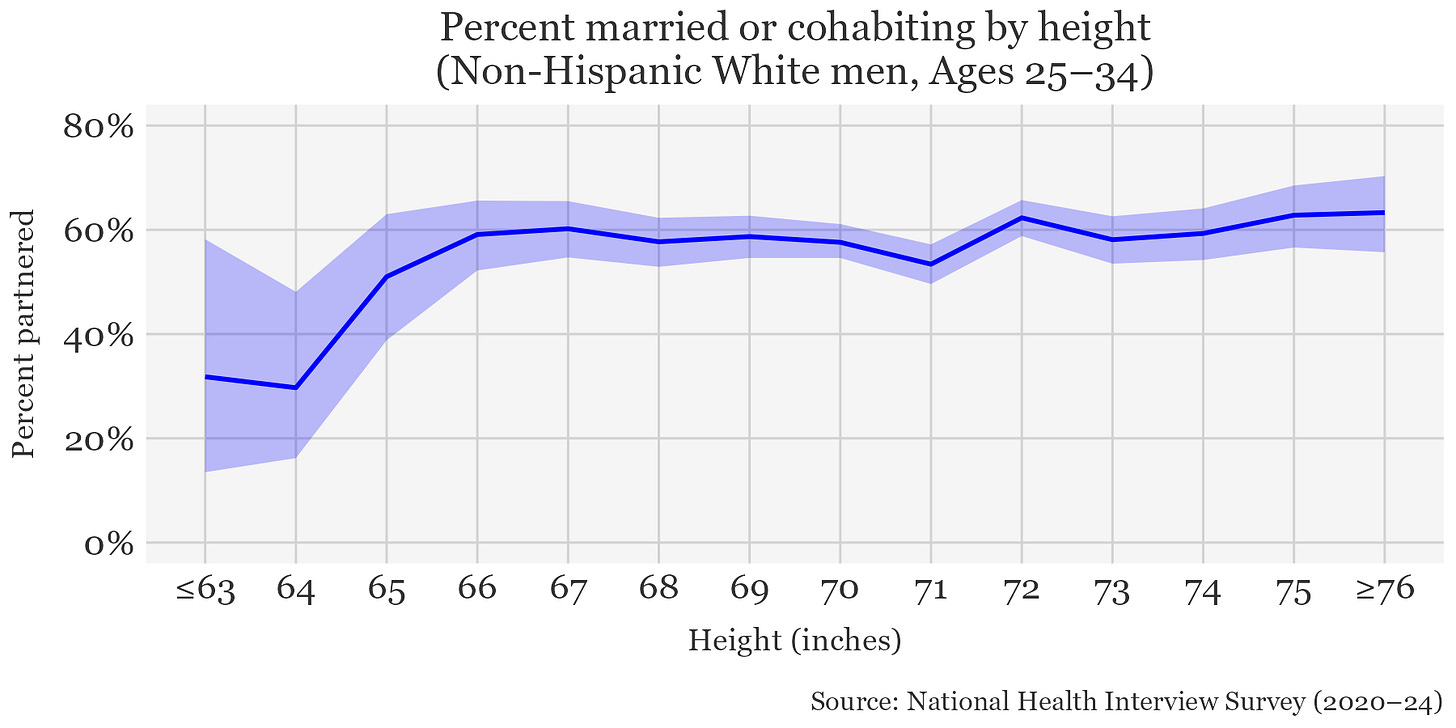

Popular discourse has it that height has a large effect on men’s dating success, which has been amplified by dating apps. Fortunately, since height is a readily measured trait, there is no shortage of data, making this claim readily testable. Here we’ll look at the percentage of men who are either married or cohabiting by height1 using the 2020–2024 waves of the National Health Interview Survey.

Among non-Hispanic white men aged 18–24, there is little variation in relationship status across the height continuum, though there’s a hint that the shortest men (63 inches or below) are somewhat less likely to be partnered.

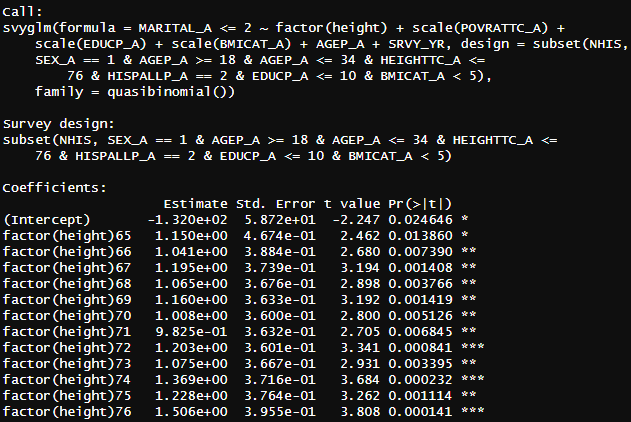

Among non-Hispanic white men aged 25–34, a clearer penalty for men 64 inches or shorter appears, comprising 1.16% of men. So men at the extreme left tail take a decent hit, but above that threshold height is effectively irrelevant.

The average height reported by women in the same age and ethnicity group was 64.7 inches, so the relationship penalty seems to become evident only when men fall below the average female height. It’s also worth considering that given self-reported height is exaggerated by roughly 1–2 cm on average among young men, those reporting 5’4 may in reality be closer to 5’3.2

A logistic regression using 64 inches or below as the reference group among non-Hispanic white men aged 18–34, controlling for education, family poverty ratio, BMI, age, finds a significant effect of heights above 64 inches on relationship status.3 Men above 64 inches overall had an odds ratio of 3.09 relative to the shortest group. Among 18–24 men, the effect remained significant (OR = 2.18) when including other ethnicities to ensure a sufficient sample size. It may have been attenuated due to 5’4 meaning something different for other ethnicities.

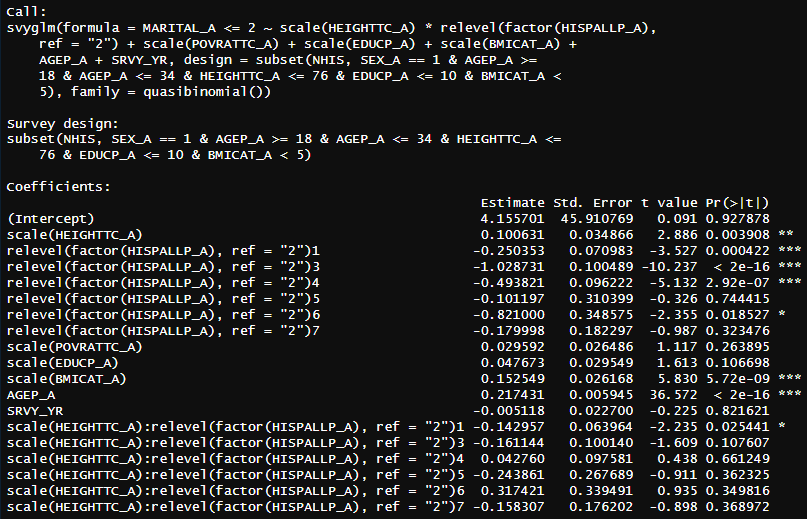

Height interacted with ethnicity in predicting relationship status. The effect is significantly smaller and not statistically significant for Hispanic men4 – which may be due to the lowest height option in this dataset being 5’3 or below, which includes 7.1% of Hispanic men – and also for black men when analysing height categorically or focusing on the 25–34 age group (there were also somewhat more black men who were 5’4 or below).

This relatively limited effect raises the question: why has such an intense fixation developed around this trait in particular?

Is heightfidence real?

One of the clever terms black pillers use to ridicule the notion that personality matters is ‘heightfidence’. The implication here is probably less that tall men are actually more confident – though this is a common view – and more that tall men are perceived as more confident thanks to the ‘halo effect’. Nonetheless, could an association with self-esteem help explain the exaggerated perception of height’s importance in dating?

Height is often considered central to manhood; tall men are perceived as more dominant and powerful. As a readily visible trait, it serves as an obvious benchmark for social comparison. It’s reasonable to expect that a lack thereof may therefore induce feelings of inadequacy. In an era where men’s relative status has declined, height may feel especially salient as a traditional status marker.

Studies have not found that short boys are more likely to be bullied or socially rejected:

Borg (1999): In a survey of 6,282 pupils aged 9 to 14, no significant differences were found in height between occasional and frequent victims, occasional and frequent bullies, occasional bullies and victims, nor frequent bullies and victims at any grade level.

Sweeting & West (2001): In a large sample of 11-year-olds, self-reported teasing and bullying, along with additional ratings from parents, teachers, and nurses, showed no difference based on height, though several other traits such as weight showed an effect.

Sandberg et al. (2004): In a sample of 956 students from grades 6 to 12, no significant relationship was detected between height and peer perceptions of friendship, popularity, or reputation. Shorter students were perceived as younger than their age.

But perhaps it’s more subtle forms of devaluation. Several early studies found no effect of height on self-esteem (Graziano et al., 1978; Hensley, 1983). Wang et al. (2017) examined 3,344 children aged 10 to 16 in rural China, finding that taller girls expressed higher self-esteem, but this wasn’t true for boys. Prieto & Robbins (1975) found a small nonsignificant effect of which was a bit higher and significant for self-evaluated height and other-evaluated height. Booth et al. (1990) found a small non-gendered effect that was nonlinear, with both short and tall people having lower self-esteem.

Gupta et al. (2015) analysed data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, finding that height had a small effect on psychological wellbeing5 in middle age, but it wasn’t robust to controls. No relationship with depression was found.

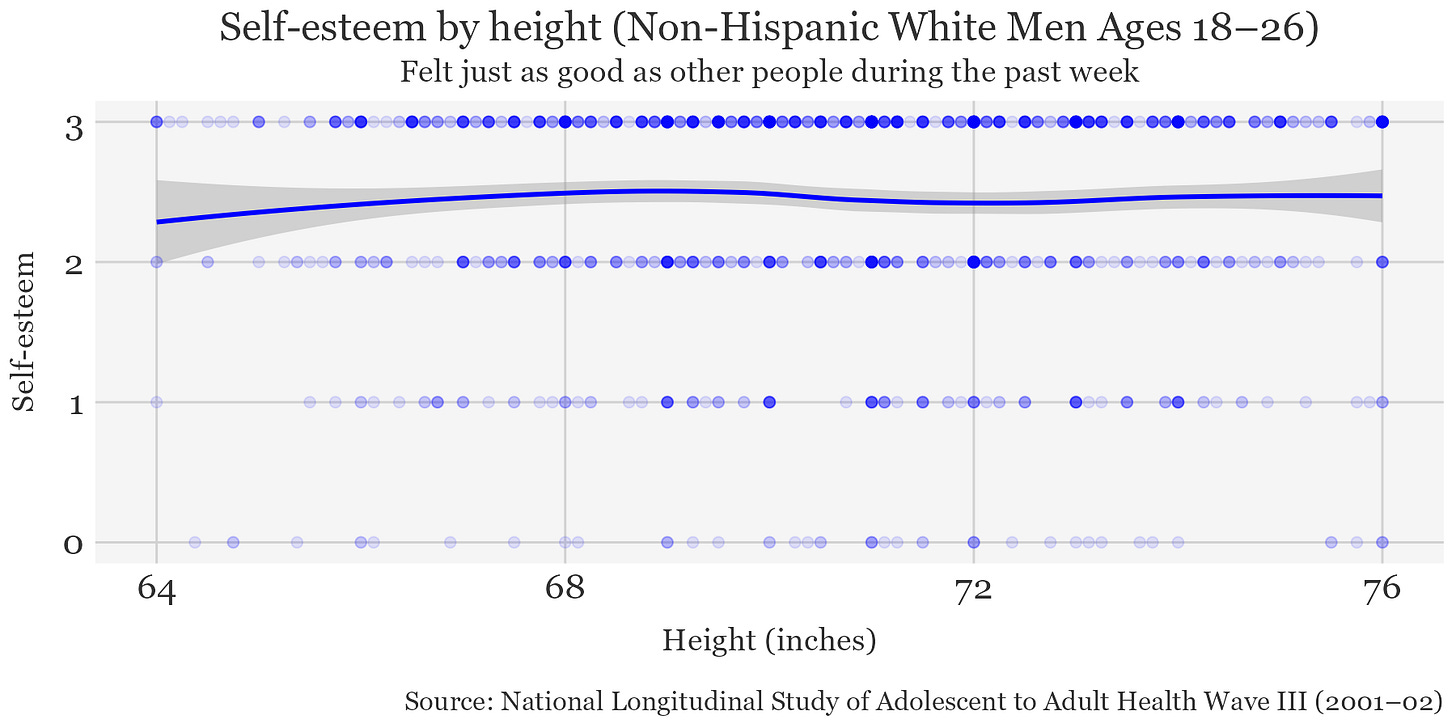

In Wave III of the Add Health survey, there was a small correlation between height and self-esteem6 for both men and women (0.05–0.06), but it was no longer significant after controlling for Hispanic status, as Hispanics were both shorter and lower in self-esteem for unrelated reasons.

Haysom et al. (2015) found no correlation between height and extraversion in a large sample of Australian twins aged around 16.

Maybe it really is all in your head, bro.

Though when specifically asked about height-related self-esteem, a clearer correlation emerges. Frederick et al. (2006) found that in a huge sample of adults, there was little association between height and self-rated body attractiveness or comfort in a swimsuit, with correlations ranging from r = .00 to .05 for both men and women. However, most shorter-than-average men desired to be taller, while most taller-than-average men were satisfied with their height. The percentage of variance in height satisfaction explained by actual height was 34% for men and 15% for women. A subsequent study found that male satisfaction with height increased until average height, after which it stabilized.

This might be somewhat biased by people feeling they’re ‘supposed’ to feel worse about being shorter, or otherwise height simply plays a very minor role in overall self-esteem. Anecdotally, this tracks – some of the most exuberant characters I’ve encountered have been some of the shortest. Also some of the most obnoxious, mind you. Regarding the ‘Napoleon complex’, one study found that dark triad traits were associated with shortness and also the desire to be taller in both sexes. They interpret these results as short people compensating with antagonistic behaviour. I don’t know about that, but thought it was somewhat amusing and worth mentioning.

The ultimate ‘immutable trait’

A large appeal of height as an explanatory variable is that it stands out among others as the most clearly immutable trait that can’t be meaningfully changed – putting aside risky, expensive procedures that you have to fly to Turkey to undergo and which will probably make you look disproportionate. Lifts and posture hacks are about all you have to alter perceived height. Factors like body composition, grooming, style, wealth, status, social skills, confidence, and facial attractiveness can be worked on to some extent. We can debate how malleable each factor truly is, but regardless, the general perception remains the same.

There is an appeal in genetic filters that block you from even getting your foot through the door, as they relieve the burden of ‘agency’ and provide a ‘justification’ for failure – it feels less like one’s ‘fault’. I use scare quotes because these frames can be criticized, but again, to understand the appeal we have to work within the frames of those who it appeals to, as well as broader society. Most people operate under the notions of libertarian free will and a highly malleable mind, where these concepts are more straightforward.

This perceived importance of a seemingly trivial and inconsequential trait dictated by a genetic dice roll is taken as validation of what is seen as a ‘cynical’ worldview whereby society is ‘superficial’7 to the point of absurdity. The idea that the system is ruthlessly rigged against men who fail to meet an arbitrary height threshold creates solidarity through a shared persecution narrative that gives their struggle meaning. A perceived hypocrisy is often drawn in that society preaches body positivity for large women but is silent on the plight of small men.

The height pill is presented as a raw truth nuke that blows up both blue pill and red pill/PUA delusions that are perceived as selling a ‘feel-good’ story that leaves room for hope and self-improvement. To embrace a rigid hierarchy wherein one’s value is determined by inherent morphological characteristics is to reject egalitarian sentimentality. The imagined psychological barriers preventing less brave souls from accepting the harsh truth about the primacy of height adds to its psychological appeal for some.

In the black pill framework, the more you exaggerate the significance of morphological characteristics like stature, the more ‘truthful’ and ‘honest’ you’re being, and the more you’re triggering Reddit soyboys and feminists. ‘Downplaying’ the role of height risks coming across as a ‘bluepilled simp’ or a ‘gaslighting tallf*g’. To maintain social cred, black pillers and co. feel compelled to place undue emphasis on it. Statements like ‘it’s over for sub-6 ft manlets’ are rewarded as ‘based’, and so the collective opinion shifts further in the ‘based’ direction over time.

The height meme ecosystem

There is a whole meme ecosystem built around height. Its visual immediacy, quantifiability, and the amusement people get from exaggerating it make it particularly meme-friendly. Certain celebrities are endlessly memed on for their height, even when they’re not objectively short.8

Memes featuring a 5’11 midget being towered over by a 6’ guy or height charts with things like ‘consider suicide’ at 5’10 or under reinforce the perceived significance of height under the guise of ironic humour and self-deprecation. Viral ragebait videos of women saying they only accept 6’ or taller men are presented by black pillers as a confirmation of their grievances.

The ‘short king’ counter-meme arose partly as ‘wholesome’ self-deprecation and as an attempt to reclaim dignity. This response might have done more harm than good by perpetuating height as a ubiquitous fixture in online discourse, not to mention the patronizing undertone that subtly reinforces the framing of moderate shortness as a serious deficiency requiring compensation.

The meme culture surrounding height helps keep the topic alive in the public consciousness, which has probably made it easier for people to accept black pill claims about its real life significance. Even mid heighters or slightly above can become paranoid and get sucked in, finding the memes intriguing or entertaining and feeling like they must be onto something if they’re so popular.

Many are apparently convinced that being 5’8 is ‘game over’ for men; not because of any real data, not even because of personal experience, but simply because it’s a trendy narrative.

The fact that height is so deeply ingrained in meme culture makes pointing to data like that presented here not only intolerable to those emotionally invested in the height pill, but also makes one a killjoy to people who enjoy the comedic side of it.

Dating apps

Dating apps have been depicted as ushering in an era of unprecedented ‘eugenic selection’ on men’s physical morphology. This is a cope; dating apps have had minimal impact on the dating landscape. I did not find evidence of an increasing effect of height on number of sex partners or relationship status following their introduction. Moreover, while the methodology may not be ideal, a mock-dating app study using a conjoint design with height shown in cm on profiles found only a very small effect.

The alleged Bumble height filter graph is one of the most widely circulated meme stats; it is most likely fake. Another way they could influence perception is by seeing ‘tall/x height guys only’ in bios, or being ghosted after height comes up. Such experiences receive disproportionate subjective weight. Even if it’s only one in a hundred or more bios, it might feel like a significant amount – especially when viral screenshots and anecdotes are added to the mix, and when men receive little attention in general.

Concluding rant

There is a predictable list of rejoinders to outcome data like this. When it comes to relationship status, the most common objection is that ‘tall Chads are slaying’, so this metric doesn’t capture what really matters. This has been addressed – the effect of height is no larger for sex partner number, nor for sexlessness. There is also a common shifting of the goalposts to partner quality. Regardless of the situation there, the discourse around height is not ‘taller men have more attractive partners’, but ‘manlets are doomed and excluded entirely’, with ‘manlet’ rarely referring strictly to genuinely short men, but being elastic enough to encompass a large share of men.

Black pillers position themselves as hyper-rational data warriors concerned only with the cold hard facts. The ‘scientific black pill’ branding makes this posture explicit. This is a facade. The whole thing is oriented around two imperatives:

1. Portraying the dating market as maximally skewed.

2. Reducing dating outcomes entirely to physical traits.

Any evidence that threatens this agenda is rejected as a ‘blue pill’ or ‘cope’. These terms are meant to denote a comforting delusion, yet are routinely used to reject any inconvenient evidence. Debunking specific claims only moves a minority of believers, and perhaps some onlookers on the fence. Similar to conspiracy theorists, they think they’ve ‘cracked the code’. This sense of revelation contributes to the allure of the black pill worldview, making tearing it down almost like tearing away someone’s raison d’être.

Some adherents will have the audacity to claim this as a victory, as if the magnitude of the effect here is in any way consistent with what the black pill preaches. In this way, the black pill becomes essentially unfalsifiable: so long as it’s ‘directionally true’ it can be declared a W. People are too quick to concede that ‘well maybe there is a grain of truth to it’. Nuance and concessions can’t be a one-sided deal.

Should some sympathy be extended to men in the bottom 1% of height who have a harder time of it? Sure. But for ‘black pillers’ who blame height when they’re 5’9 or something, it’s pure cope, and if anything stolen valour from the real Oompa Loompas out there.

Having now looked quite thoroughly at the empirical reality (in previous articles mostly), I find myself questioning why there is such a vast discrepancy between the modest predictive power of this trait and the dramatic impact so many believe it to have. I’ve had a crack at it here, but I’m sure there’s more to say on it.

While men and women both overstate their height a bit, self-reported and measured height correlate highly – above 0.9 for young men.

Though as men get closer to six feet they round up a bit more than usual (the overall exaggeration is a bit stronger than usual here due to it being an online dating website).

Aggregate of personal growth + purpose in life + self-acceptance + environmental mastery.

Feeling just as good as other people during the past week.

I’m not convinced this is a coherent concept.

Cool. As a 5'4 turbomanlet, I'm extremely justified in my perception that I'm at a SIGNIFICANT disadvantage, and the blackpill is truer than anything. I've literally always been correct that I'm playing life on legendary mode.

Interesting data!

Of course, it could be that shorter people have to “settle” more, even if they are still partnering up at similar rates. But the data fully debunk the “game over” hypothesis.