Was Widespread Polygyny the Historical Norm?

Is it true that prehistoric Chads excluded the vast majority of men from reproduction?

The question of what mating system humans are naturally built for has long inspired speculation and debate. Some argue that humans belong to the minority of mammals inclined towards monogamy; others propose a bonobo-like free love model à la Sex at Dawn; and others a gorilla-like harem model à la Hugh Hefner.

In recent years, the notion that human mating—absent the ‘artificial’ top-down imposition of monogamy—defaults to a polygynous, winner-takes-all dynamic has gained considerable traction. One popular narrative frequently presented in support of this notion depicts prehistoric Chads greedily monopolizing women and condemning the vast majority of their fellow tribesmen to genetic oblivion. This claim has been widely circulated through a screencap of an article whose headline reads: ‘8,000 years ago, 17 Women Reproduced for Every One Man’.

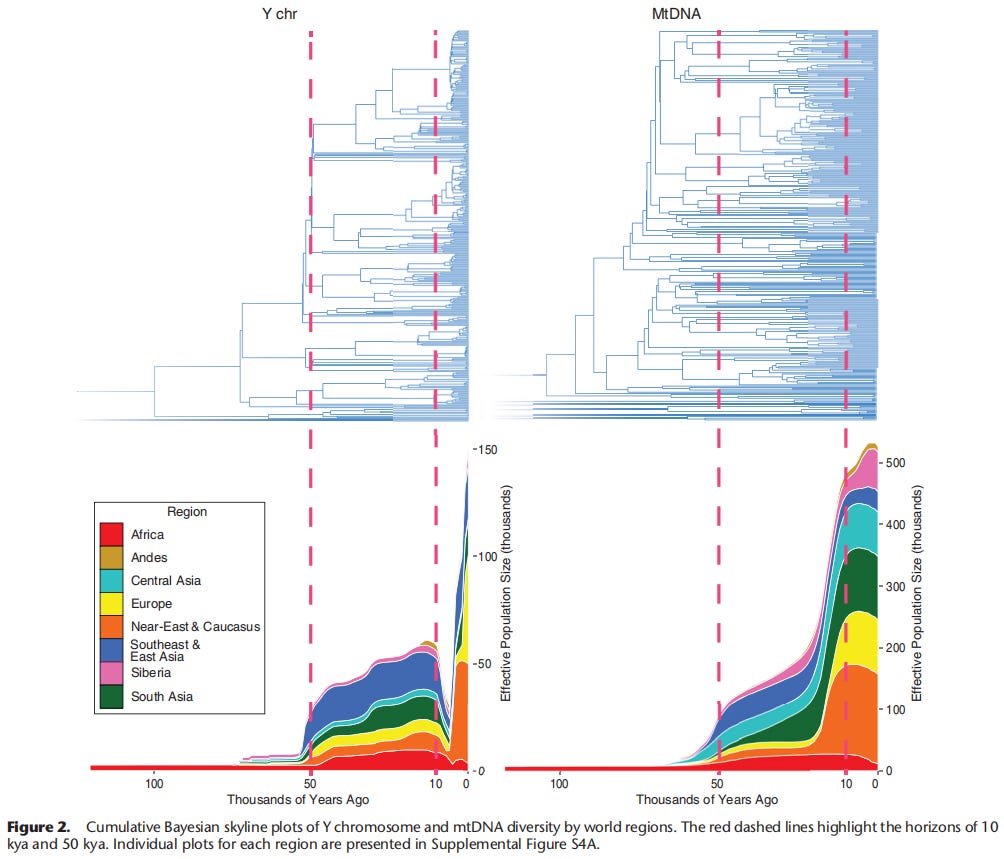

The study on which this claim is based analyzed Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA from 110 populations worldwide, revealing a peculiar anomaly: a drastic decline in the effective male population between 8,000 and 4,000 years ago, without a corresponding decline in the female population.

Explaining Y’s relative uniformity

This finding has of course been enthusiastically embraced by the manosphere, as it appears to validate the framework of intersexual dynamics central to their worldview. After all, what argument is there when science has shown it’s baked into our very DNA? For instance, Myron from Fresh & Fit in a podcast1 with Destiny and Sneako put it like this (while omitting the fact that this bottleneck was specific to the Neolithic era):

Historically speaking, since the beginning of time, one man has procreated for every seventeen women. So what does that mean? That tells you that women were concentrating on a very small minority of men and a small minority of men were having sex with a majority of the women, because women are hypergamous by nature and pick the best guys.

This widespread historical inceldom is often pointed to as a cautionary tale of what happens when hypergamy isn’t kept in check by enforced monogamy, framing the supposed Chadopolization of today’s dating market as merely a reversion to the natural order of mass polygyny.

Although the manosphere has no doubt played a role in popularizing this interpretation, it would be a mistake to dismiss it as solely confined to this sphere. After all, we even see feminists now promoting it, reframing it as ‘empowering’. Moreover, the authors of the study themselves suggest a similar idea:

The temporal sequence of the male Nₑ decline patterns among continental regions is consistent with the archaeological evidence for the earlier spread of farming in the Near East, East Asia, and South Asia than in Europe. A change in social structures that increased male variance in offspring number may explain the results, especially if male reproductive success was at least partially culturally inherited.

So, this interpretation is actually not particularly controversial. The shift appears to coincide with the Neolithic transition from hunter-gathering to agriculture across the Old World. The rationale behind the hypergamous mass harems explanation for this genetic bottleneck is that, following this transition, property ownership and wealth accumulation were introduced into society, intensifying social and material inequality. Faced with the choice of sharing one of these high-status alphas or settling for the average Joe Flintstone, women would opt for the former, and this inequality would be perpetuated through the inheritance of wealth and social status along the male line.

The idea is that this arrangement satisfies both men’s desire for sexual variety and women’s desire for access to resources, while also possibly securing ‘good genes’, assuming that status serves as a proxy for genetic quality.

The headline of the article claiming that only one man reproduced for every woman was overzealous, as the data doesn’t directly represent the ratio of males to females who were reproducing at the time. What it instead shows is the ratio of male to female genetic lineages that managed to survive to the present day. Variance in male reproductive success mediated by polygyny is not the only possible mechanism that can influence Y-chromosomal diversity patterns.

Sex-biased migration

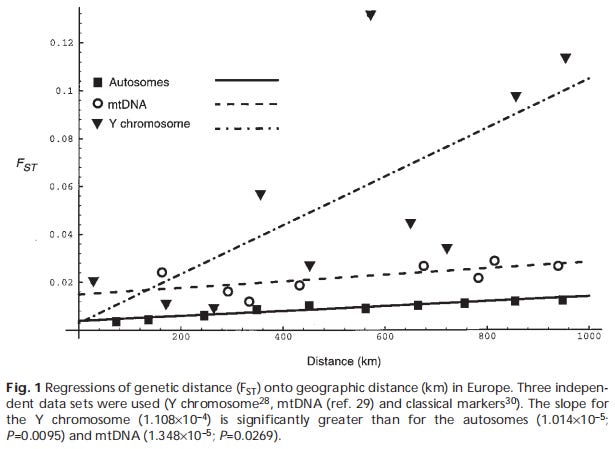

Seielstad et al. (1998) observed that Y chromosome variation in 14 African populations was more geographically localized than mtDNA or autosomal variation, and proposed that the practice of patrilocality—where women relocate to their husbands’ households—resulted in a female transgenerational migration rate around eight times higher than that of males. This in turn caused diverse Y chromosomes to be introduced into populations at a lower rate compared to mtDNA or autosomes.

In a strictly monogamous population, the effective population size (Nₑ) for autosomes is expected to be four times greater than for Y-DNA and mtDNA, as autosomes are inherited from both sexes. Polygyny also reduces the autosomal Nₑ, increasing this ratio. From a sample of 66 populations, they calculated a global autosome-to-Y ratio of 4.27—only slightly above the expected value. They estimate that polygyny likely accounts for less than 10% of the reduction in Y-DNA diversity, with most of the effect attributable to patrilocal residence patterns.

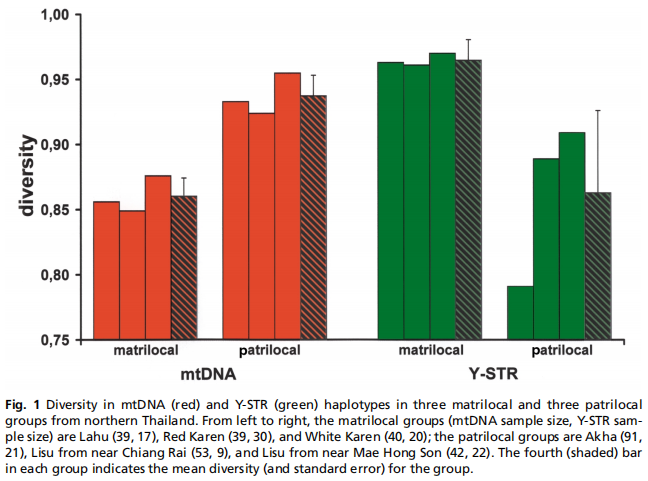

Oota et al. (2001) corroborated this hypothesis by examining three patrilocal and three matrilocal hill tribes of northern Thailand. The expected pattern held for the patrilocal groups: Y-DNA showed lower diversity and greater genetic distances between populations. Conversely, among the matrilocal groups, mtDNA exhibited lower diversity and greater between-group differentiation.

Similarly, Gunnarsdóttir et al. (2011) compared the matrilocal Semende and patrilocal Besemah groups from Sumatra, finding lower mtDNA diversity in the Semende. Contrary to expectations they found no difference in Y-DNA diversity. Verdu et al. (2013) compared Pygmy and non-Pygymy populations in Central Africa. While non-Pygmy groups exhibited typical patrilocal patterns, Pygmy groups showed patterns more akin to matrilocal societies, with higher male than female effective population sizes and migration rates. This disparity likely arises from social prohibitions on marriages between non-Pygmy women and Pygmy men, while Pygmy men often marry non-Pygmy women due to lower bride prices. Social discrimination against Pygmy women in non-Pygmy villages leading to divorce, or the death of a non-Pygmy husband, would often result in the return of Pygmy women and their mixed children to the woman’s home village, contributing to the gene flow of non-Pygmy male lineages into Pygmy populations.

Lower within-group diversity naturally leads to greater between-group differentiation. Bolnick et al. (2006) analyzed 16 Native American groups and found higher mtDNA variability in the southeast where most groups practiced matrilineality and matrilocality, and higher Y-DNA variability in the northeast where most groups practiced patrilineality and patrilocality.

Chromocide

Returning to the Neolithic bottleneck, is the mass harems explanation really plausible? On the surface, a 1:17 ratio seems a bit absurd—this is approaching elephant seal territory. Did 95% of men really just accept their fate, toiling away in the fields from cradle to grave with no hope of fulfilling their primary biological imperative? It’s nearly twenty men to one; why was there not a successful ‘beta uprising’ during this time?

This is where Zeng et al. (2018) step in, with a hypothesis built around violent intergroup competition between patrilineal kin groups.

As nomadic hunter-gatherers settled into agrarian societies, unilineal kin structures—typically patrilineal—became the dominant form of social organization. There appears to be a U-shaped curve wherein these systems are most common in societies of middling complexity.

Marlowe (2004) found that patrilocality was much more prevalent among non-foragers than foragers, with 60% and 34% practicing it, respectively, while only 15% of non-foragers and 23% of foragers were matrilocal. Non-foragers were also much more likely to be patrilineal (47%) than were foragers (14%). Across all societies, patrilocality correlated with patrilineal inheritance of land (r = .39) and movable property (r = .34).

The rise of patrilineality and patrilocality alongside the development of agriculture may reflect the need for a formal system of inheritance to pass down land and resources. Sons provided a clear line of succession and could better make use of these resources due to their greater reproductive potential. The more mobile foragers, by contrast, have less need for systems of inheritance, as land is not privately owned and they don’t accumulate as many resources across generations. Marlowe also found that unilineal descent was more common among the more sedentary foragers.

Patrilineality was especially widespread in warrior societies without centralized authority. One reason for this may be that it strengthens group cohesion, making it easier to rally men in times of crisis. Marlowe’s study also found that internal warfare correlated at r = .42 with patrilocality, and that internal warfare was rare among foragers, perhaps owing to less competition over resources and more egalitarian social structures.

Since Y-DNA tends is passed down through the male line, it tends to be more homogeneous within patrilineal groups and more heterogeneous between them. The implication is that, in the event one group is eradicated by another in warfare, it could mean the extinction of its entire male lineage. Thanks to women marrying across tribes, their lineages were more widely dispersed, making them more resilient to extinction. Additionally, women were more likely to be ‘absorbed’ by a conquering tribe rather than slaughtered along with the men. The upshot is that, over time, this process would erase many Y-DNA clades, leaving no trace in the genetic record and creating the illusion of a drastic increase in reproductive skew among males.

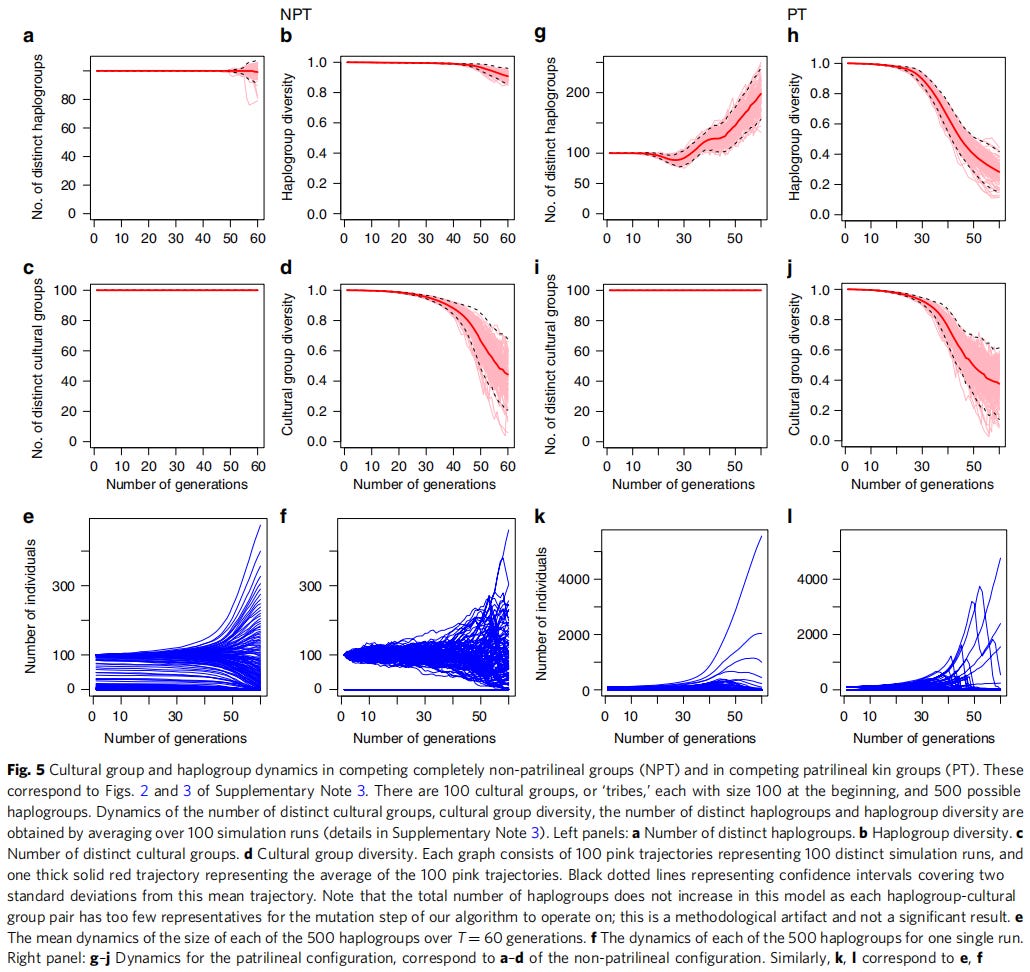

They also generated mathematical models in which 15% of males are killed in each generation. These models show that, in patrilineal systems, it doesn’t take long before a significant number of haplogroups begin to go extinct, while one or a few dominate and rapidly increase in frequency. In simulations without patrilineality, on the other hand, few or no haplogroups go extinct, and each remains similarly common by the end of the simulation. Since rapid increases in the frequency of haplogroups over short time spans can lead to a quick rise in mutations among their members due to their higher numbers, this may help explain the ‘star-shaped bursts’ observed in the Y-chromosome phylogenies of dominant clades in modern populations.

They cite findings from studies on Central Asian pastoralists in support of this hypothesis:

Central Asian pastoralists, who are organized into patriclans, have high levels of intergroup competition and demonstrate ethnolinguistic and population-genetic turnover down into the historical period. They also have a markedly lower diversity in Y-chromosomal lineages than nearby agriculturalists. In fact, Central Asians are the only population whose male effective population size has not recovered from the post-Neolithic bottleneck; it remains disproportionately reduced, compared to female estimates using mtDNA. Central Asians are also the only population to have star-shaped expansions of Y-chromosomes within the historical period, which may be due to competitive processes that led to the disproportionate political success of certain patrilineal clans.

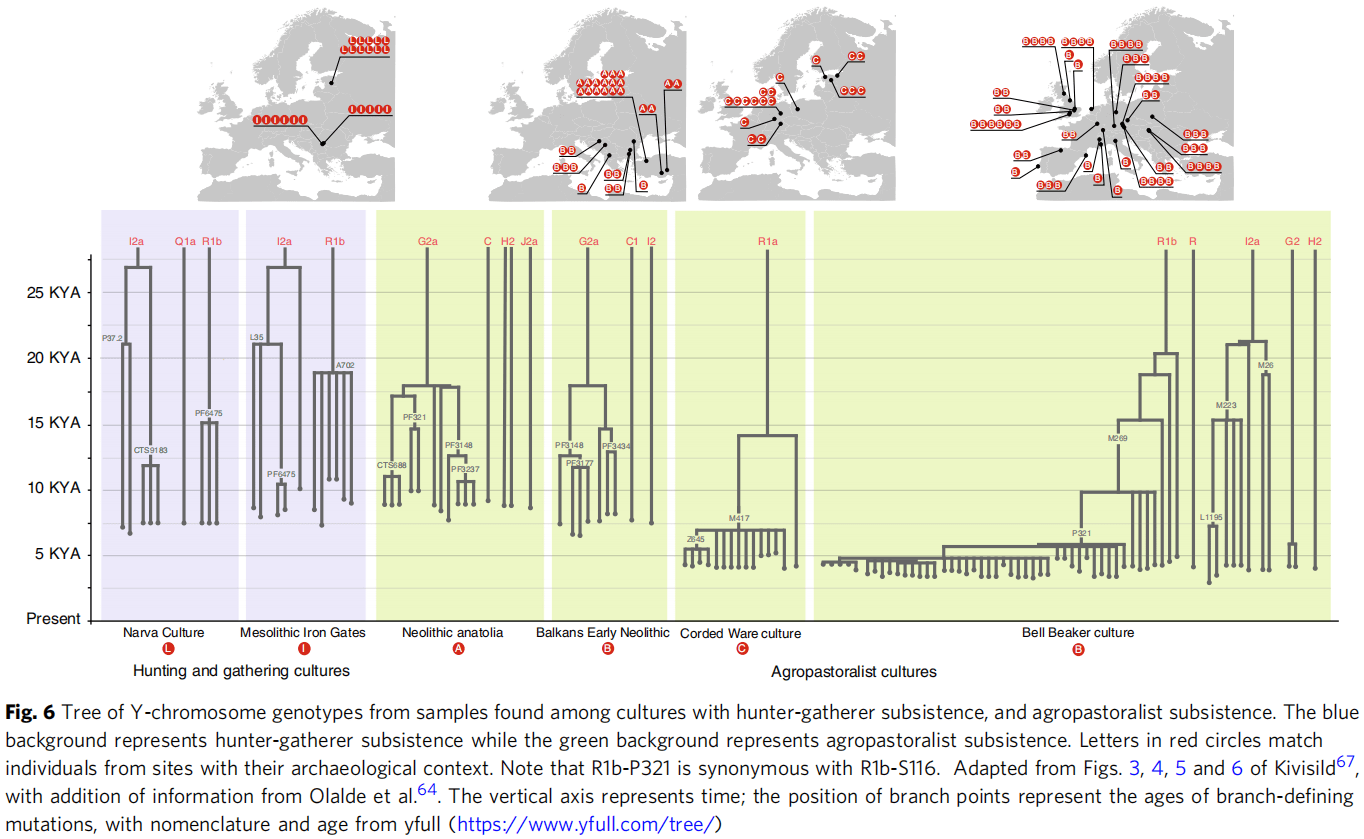

Phylogenies constructed from ancient DNA samples found across Europe show that the Y chromosomes of farmer and pastoralist cultures are more homogeneous and have more recent coalescences than those of hunter-gatherer societies.

As societies grew more complex and centralized, the relevance of corporate kin groups diminished. Non-kin agencies, such as emerging state structures, began to fulfill many of the roles once occupied by kin groups, while individuals sought economic and occupational opportunities outside of these traditional structures. Warfare between kin groups also tended to be suppressed. This could explain the timing of the bottleneck's end at the conclusion of the Neolithic era.

A peaceful alternative

Guyon et al. (2024) highlight inconsistencies in estimates of violence rates during certain periods due to limitations in the archaeological record, such as small sample sizes. This renders dubious the relatively high 15% generational male mortality rate assumed by Zeng et al., even if it could explain the bottleneck—a conclusion also called into question by their analysis. Instead, they offer a more ‘peaceful’ explanation for the bottleneck.

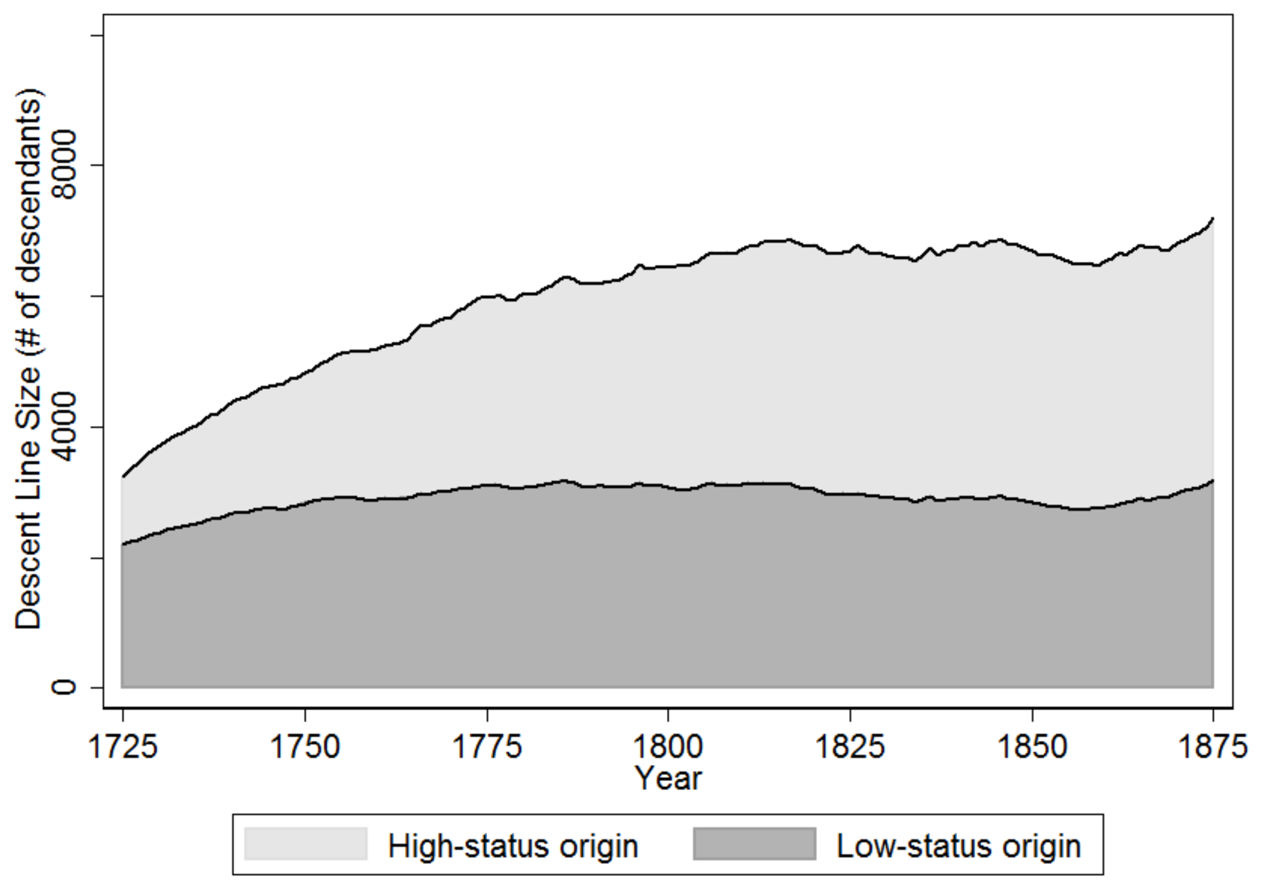

Higher status lineages are more likely to persist over time through an accretive process. This concept is explored by Song et al. (2015), who analyzed multi-generational data on Chinese men during the Qing dynasty, comparing those at opposite ends of the social spectrum—imperial lineage and farmers—to assess how status transmission influenced the long-term success of paternal lineages. In historical China, status and property were typically passed down patrilineally, and the continuation of the patriline was considered vital. Sons carried on the family name, supported their parents in old age, and were more valued as workers. Of course, this preference for male children was also evident in modern China where the one-child policy drove many families to abort female fetuses.

What the study shows is that the status of paternal ancestors not only influenced their representation in later generations because of their direct reproductive success, but also that of their descendants. From 1725 to 1875, patrilines with high status founders experienced rapid growth, increasing from less than a third of the population to more than half. Half of high status patrilines went extinct during this timeframe, while almost three-quarters of low status patrilines did. This occurred despite polygyny being rare, even among the imperial lineage.

Another interesting finding was that the long-term success of high status patrilines was driven not by maximizing offspring quantity, but by minimizing the risk of extinction. This aligns with the ‘slow life history strategy’ in life history theory—investing heavily in a limited number of offspring to ensure they reach adulthood and achieve high status—rather than dissipating family wealth.

Returning to Guyon et al., they examine how variance in reproductive success between patrilineal groups interacts with segmentation, or ‘fission’. In some patrilineal systems, descent groups split along genealogical lines when they reach a certain size.

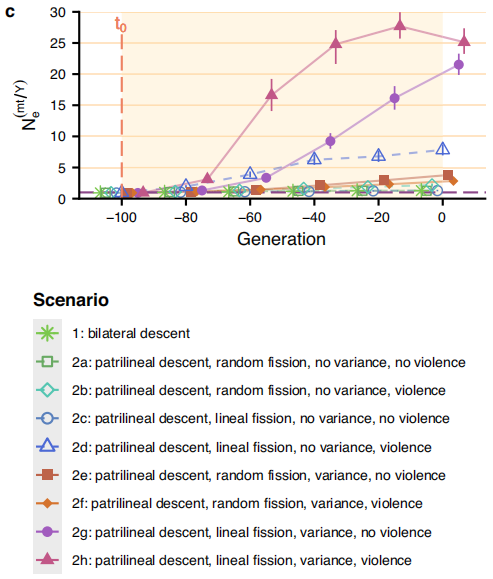

Simulations were conducted under various sociodemographic scenarios: patrilocal villages following either bilateral or patrilineal descent rules, undergoing random or lineal fissions, and with or without variance in reproductive success, violent intergroup competition, limited male migration, and post-fission migration of the smallest newly formed groups.

Lineal fission, by sorting Y chromosomes more efficiently than random fission, significantly intensified the bottleneck. When combined with reproductive variance, it also had a markedly stronger impact on the male Nₑ than did violence.

Purifying selection

Another mechanism worth mentioning that may contribute to the lower diversity of the Y chromosome was outlined by Sayres et al. (2014), who analyzed genomic data from 16 unrelated men. The reduction in male Nₑ required to explain the Y-chromosomal data would lead to levels of normalized autosomal, X-chromosomal and mtDNA diversity that were inconsistent with the observed data, which rules out greater reproductive variance among men as the sole explanation.

On the other hand, models of purifying selection—whereby deleterious mutations accumulate over time because the Y chromosome doesn’t undergo recombination—were able to account for the low Y-chromosomal diversity, provided that purifying selection acts on more than just the few remaining coding regions on the Y chromosome. This aligns with findings showing that the number and types of functional genes on the Y chromosome are highly conserved across humans and other primates, suggesting that purifying selection plays a significant role in maintaining these genes.

This might not be able to explain the sudden bottleneck across multiple isolated populations at roughly the same time around the world, but it could help explain the lower Y-DNA diversity seen outside of this period.

Reasons to doubt mass harems

Now that we’ve explored some alternative explanations, what makes mass harems a less plausible explanation?

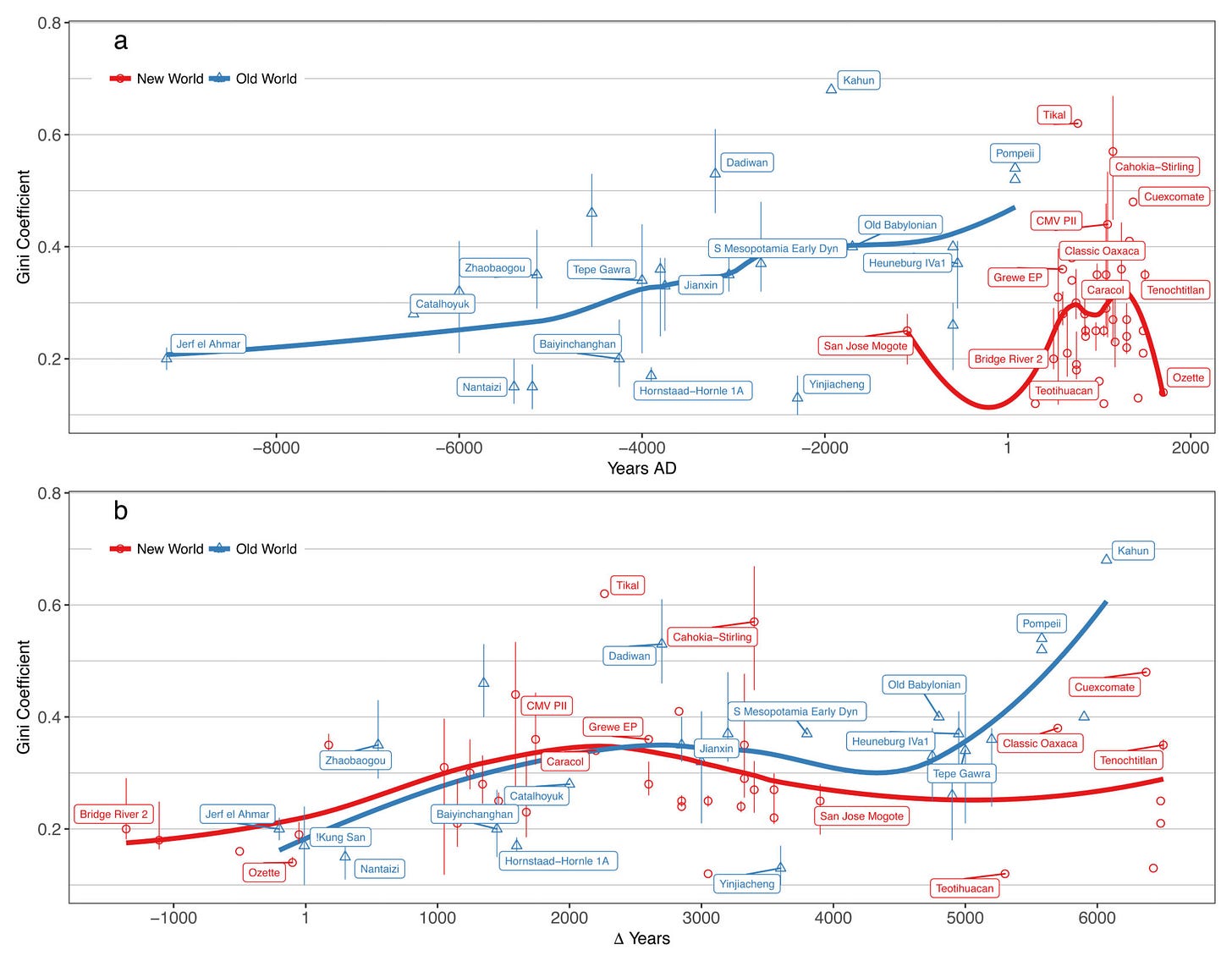

The bottleneck lifted without decreasing inequality

A naïve model of polygyny being determined by inequality would predict that it would have continued to rise following the rise of civilizational states, where wealth only became more concentrated and power more centralized in the hands of elites. Despite this, it is precisely when the Neolithic bottleneck is lifted, which seems at odds with the notion that inequality was driving the bottleneck through its influence on men’s reproductive variance.

Agriculture doesn’t predict higher polygyny or reproductive skew

The mass harems hypothesis predicts that the agricultural revolution intensified polygyny by widening the gap between the top and bottom men, incentivizing the sharing of access to the top men.

Interestingly, others have argued that the agricultural revolution is actually what led to the rise of monogamous nuclear families. Fortunato & Archetti (2010) suggest that monogamy spread in Eurasia alongside growing concerns over inheritance, perhaps as a way to prevent estates from diminishing in value through division among multiple heirs or to minimize disputes.

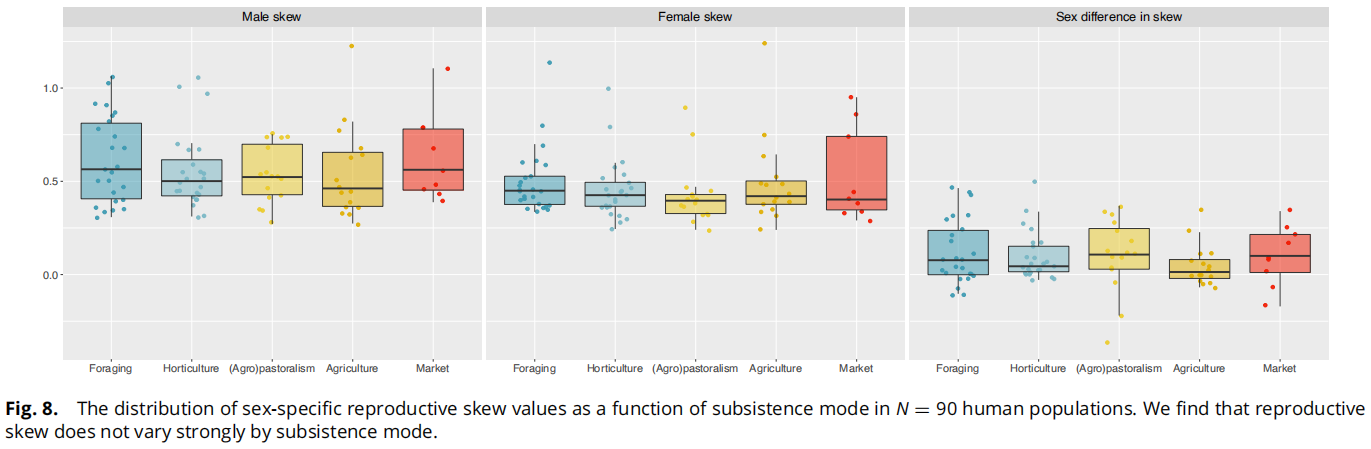

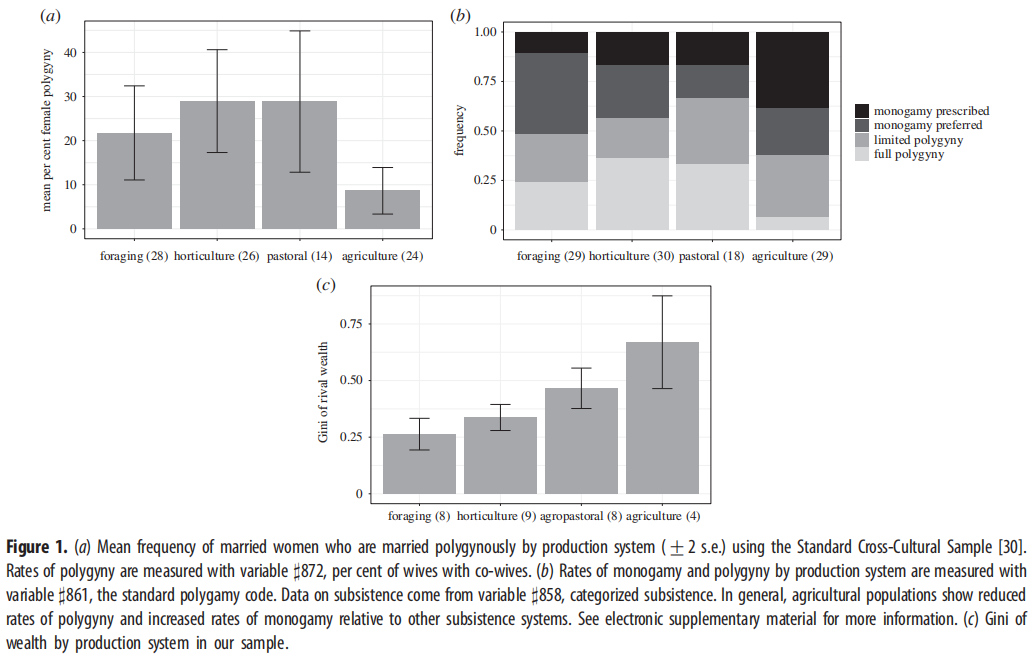

A meta-analysis by von Rueden & Jaeggi (2016) found that across 33 nonindustrial societies, the effect of status on men’s reproductive success did not vary by subsistence type or status measure. Likewise, Ross et al. (2023) found no significant difference in men’s reproductive skew as a function of subsistence strategy across 90 populations. The sex difference in skew was also quite minimal.

The notion that after a certain point of inequality, women decide it’s better to be the second (or seventeenth) wife of one man than the exclusive wife of another is known as the ‘polygyny threshold model’. However, Ross et al. (2018) observe a ‘polygyny paradox’: despite higher wealth inequality in agricultural societies, polygyny rates are lower compared to other types of societies. Maximum harem sizes have also been observed to be smaller among agrarians.

Though polygyny is often associated with wealth within countries, at the macro level, there is no correlation between a society’s Gini coefficient and its polygyny rate. The authors make the case that agricultural stratification increases the share of poor individuals while simultaneously reducing the share of men with sufficient wealth to secure multiple wives. Moreover, diminishing fitness returns to additional wives leads rich men to take less wives than their wealth would allow. Therefore, a society with a high Gini driven by a bunch of paupers and a small elite won't necessarily support widespread polygyny.

This reduction in ‘marginal fitness returns’ refers to factors unrelated to a male’s need to divide his wealth between wives. The authors outline several possible reasons for this, while acknowledging that they could have overlooked some form of wealth. One possibility is that wealthy men deliberately limit their reproductive output. Beyond resources, the time and attention a man can invest in his offspring may also be crucial. It could become more challenging to ‘mate guard’, making an incel rebellion more likely. Another potential limiting factor is STDs: the more wives a man has, the higher the chance one may contract an STD, which could spread and render other wives infertile. Finally, the more wives a man has, the more co-wives there are to be jealous of, which could reduce their willingness to cooperate.

Ancient DNA

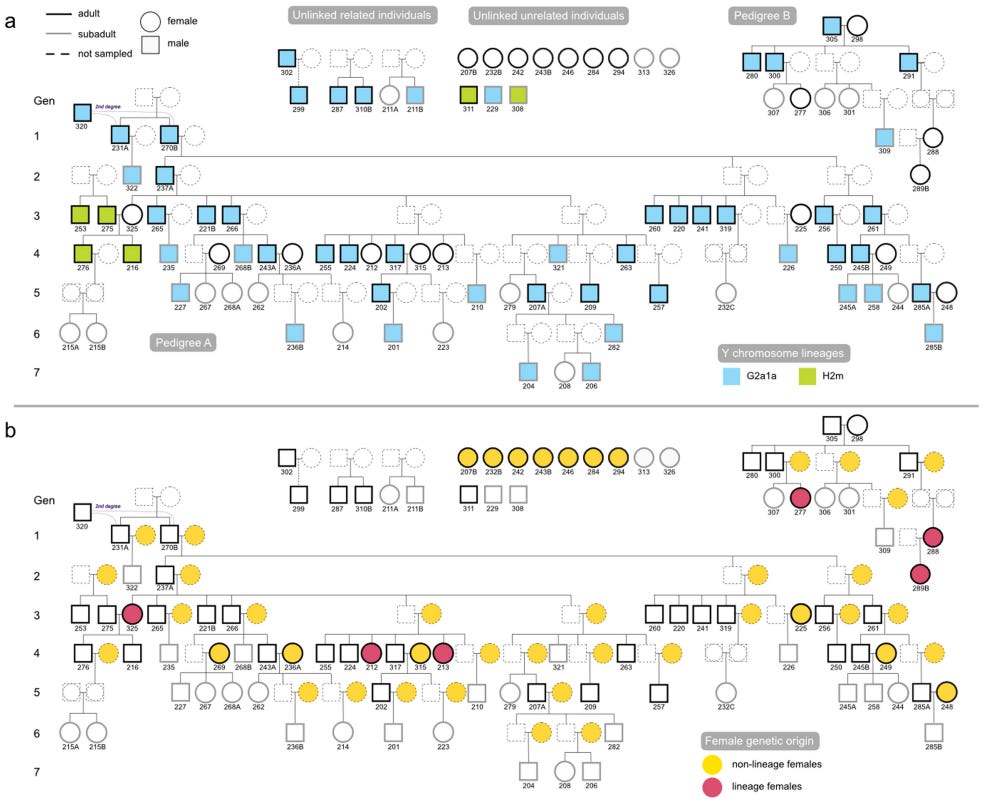

Kinship analyses using ancient DNA from Neolithic and Bronze Age European burial sites consistently reveal patrilineal and patrilocal social structures: men typically share a common paternal ancestor, while women are more likely to come from outside the community (Mittnik et al., 2019; Sánchez-Quinto et al., 2019; Schroeder et al., 2019; Furtwängler et al., 2020; Seguin-Orlando et al., 2021; Chyleński et al., 2023).

They also seem to indicate that monogamy was the prevailing system in these communities. Villalba-Mouco et al. (2022) analyzed 68 individuals buried at La Almoloya, a site in the Bronze Age Iberian state of El Argar. Pedigrees spanning up to five generations were traced exclusively through the paternal line, and there was an absence of maternal relatives among adult women, a lack of adult daughters buried alongside parents, and a deficit of second-degree female relatives. These findings suggest a patrilineal and patrilocal social structure with reciprocal female exogamy. While some individuals were half-siblings, the absence of multiple or triple burials suggests that serial monogamy was more likely than polygyny.

Fowler et al. (2022) analyzed ancient genomes of 35 individuals in British tombs dating to ~5,700 years ago, with 27 forming an extended pedigree. All 15 intergenerational transmissions were paternal, and while lineage men had children with non-lineage women, no adult daughters remained in the burial. This suggests a patrilocal structure and female exogamy. One male progenitor had children with four women, which could indicate either polygyny or serial monogamy. I also counted four women who had children with two men, one man who had children with one woman, and six relationships appeared completely monogamous.

Blöcher et al. (2023) analyzed 32 genomes from a burial mound of a 3,800 year old Central Eurasian pastoral community. The absence of related female children over five years old and the higher genetic diversity among adult females than males suggested patrilineality and patrilocality. One man had eight children with two women (seven were with one), indicating either polygyny or serial monogamy, while the other four relationships were monogamous.

Rivollat et al. (2023) analyzed ancient genomes from a French Neolithic burial site dating to 4,850–4,500 BC. Across seven generations, descent was traced almost exclusively through the male line, with 51 of 57 males sharing a single Y-chromosome haplogroup. Only six of the 20 adult women buried were descendants of the main pedigree, and most adult mothers present had no ancestors buried at the site, indicating exogamy.

Perhaps most notably, they found a distinct absence of half-siblings in the sample. Unless polygamous offspring were buried elsewhere, this strongly suggests that this was a monogamous community.

Polygyny’s prevalence in recorded history

Anthropologists have traditionally classified societies as ‘monogamous’ only if they explicitly prohibit polygamy, whereas merely permitting the practice has led to societies being labelled ‘polygynous’. Broad statements like ‘85% of cultures are polygamous’ have been repeated ever since the creation of the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample—a dataset consisting of 186 nonindustrial societies that had been studied.

In a number of cultures monogamy is the predominant mating system; however, most cultures (about 85%) are polygamic. For humans, the optimal evolutionary strategy is monogamy when necessary, polygamy when possible.

Or:

Modern societies—those that have grown out of the Christian Middle Ages—are remarkably monogamous. They seem, in fact, so consistently monogamous that what was once the rule looks like an exotic exception. The vast majority of human societies has been polygynous (e.g., Murdock 1967; Low 1988; White 1988).

Or:

To start by trying to explain polygyny is to start from the wrong end. As far as human cultures are concerned, it is monogamy that is rare, polygyny is common.

Or:

In fact, for almost all of written human history, the vast majority of humans lived in polygamous societies.

Or:

Polygynous mating eventually evolved into polygynous marriage, which has long been the dominating marriage institution, and still characterizes most contemporaneous traditional societies.

However, such statements provide limited informative value without knowing the frequency at which polygyny is actually practiced in these societies. To address this, we turn to more recent history, where the prevalence of polygyny can be assessed more directly, without relying on dubious extrapolations. If polygyny were indeed the default social structure, requiring strict restrictions to prevent its spread, we should presumably expect to see clear evidence of this where such restrictions are absent.

Forager societies

While nonindustrial societies have by no means remained frozen in time, they at least offer a closer approximation of how our distant ancestors might have lived. In the total sample of 186 forager and non-forager societies in the SCCS, among those without missing data, in only 34% were at least 20% of married men polygynous. In another study which included additional data sources for a total of 212 forager societies, 14.1% of married men and 21.4% of married women were involved in polygynous marriages.

Among the ǃKung, a subgroup of the San people, who represent the oldest known genetically distinct population, only 5% of marriages in the Dobe area were polygamous in 1964, including six cases of polygyny—with only one of them having three wives—and one case of polyandry. This was despite 16% of women over 15 being divorcees or widows and women providing more than half of the household’s food, meaning they weren’t a significant economic burden. Many men expressed a desire for a second wife but feared their first wives’ reactions.

Hewlett (1996) provides data on four Pygmy tribes, with polygyny rates of 3% among Efes, 14% among Mbutis, 19.5% among Bakas, and 17.5% among Akas. The lower rate among Efes may be due to Efe women frequently marry Lese farmer men, reducing the number of marriageable Efe women.

Sharp (1940) analyzed census data from 1933–1935 for four Aboriginal tribes, two of which hadn’t yet come under European influence. Among married bushmen, 19% were in polygynous unions, with nine men having two wives, two having three, and none having more than three. There were hints that the practice of polygyny had waned over time, as eight monogamously married men were formerly polygynous, and genealogical records suggested that polygyny was more common in the past and involved a larger number of wives—though there were no recorded instances of a man having more than six.

There were 146 marriageable women to 91 marriageable men, a ratio of 1.6 women per man. Men typically married around age 25 after completing their initiation, leaving 90% of post-pubertal males under 25 unmarried. The remaining 10% were mission students who were pressured to marry to legitimize births or sexual relations. Among adults over 25, 15% of men and 25% of women were unmarried, though only 7% of men and 2% of women had never been married. Females, by contrast, often married upon reaching puberty, though this was less common among those at the mission—25% of young mission women were married compared to 50% of bush women. In addition, male mortality was higher. It’s argued that these factors are what made polygyny feasible.

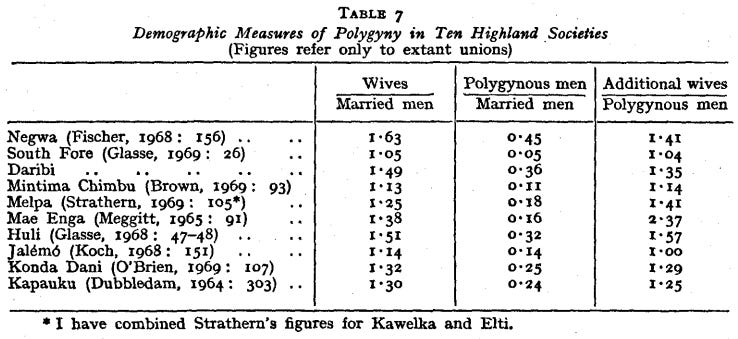

Wagner (1972) presents data on ten Highland Papuan societies, showing polygyny rates between 5–45%, with an average of 22.6%. Apparently, the low rate of 5% in South Fore is attributable to a neurodegenerative disease called ‘kuru’, which was spread through ritualistic cannibalism and caused the ratio of women to men to decline due to women and children being in charge of preparing the bodies and eating the brains.

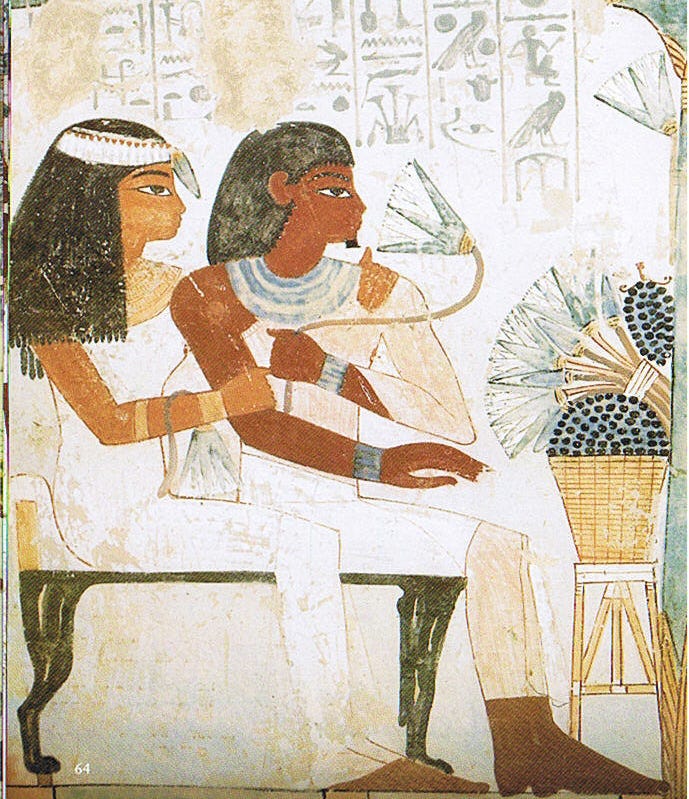

The ancient world

It’s ironic that the image of farmers threshing grain on the ‘1 in 17’ article is from the tomb of Menna. This same tomb, belonging to an 18th Dynasty (1539–1292 BC) official, depicts him accompanied not by seventeen wives, but by one. This pattern holds true for most elite men’s tombs, despite the lack of explicit prohibitions on polygamy. Even in the minority of tombs that appear to leave the door open to polygamy, they may instead tend to represent remarriages following the death of a wife.

Instructional texts that provided moral guidance, such as the Maxims of Ptahhotep written by the Vizier Ptahhotep around 2375–2350 BC, encouraged men to simp for their wife (singular):

If thou wouldest be wise, provide for thine house, and love thy wife that is in thine arms. Fill her stomach, clothe her back; oil is the remedy of her limbs. Gladden her heart during thy lifetime, for she is an estate profitable unto its lord. Be not harsh, for gentleness mastereth her more than strength. Give to her that for which she sigheth and that toward which her eye looketh; so shalt thou keep her in thine house.

The historian Herodotus wrote in the 5th century BC in Histories: ‘Those who inhabit the marshes have the same customs as the rest of Egyptians, even that each man has one wife just like Greeks’. Pharaohs were an exception: it was common for them to have multiple wives and concubines, primarily to ensure the production of an heir and to form political alliances.

The Code of Hammurabi—a Babylonian legal text from 1755–1750 BC—makes it clear that monogamy was the default marriage arrangement, though polygyny was permitted in specific circumstances. However, a decree mandating slave-concubines and their children be freed upon their master’s death indicates that men were allowed sexual slaves alongside their wives.

In An Assyrian Doomsday Book (1901), C. H. W. Johns analyzed a 7th century BC census from the district surrounding the Assyrian city of Harran. He drew the following conclusions regarding marriage structures:

Clearly man and wife form the nucleus of the family. When a man married, he left his father and mother 'to cleave* to his wife. Each family so constituted seems to have inhabited 'one house . But when a man had grown up sons, and more than one 'wife' or 'woman' is mentioned, we may suppose that married sons remained in their father's house. I think that less likely than the alternative that a man took to himself more than one wife. When we find more than one wife but only one son, the suggestion to my mind is that the first wife having proved childless, the local public opinion justified the taking a second wife for sake of an heir. As the daughters are separately entered, the term 'woman' can hardly be meant to include all the females of the family. Some may have been 'concubines': but there is no suggestion that the term 'sister' is applied to them. … We may assume then that monogamy was the rule, though plurality of wives is very common. A man might have his mother living with him, and was then probably unmarried, or a widower. In 68 families no less than 94 females occur: entitled 'wives'.

It’s generally agreed upon that polygamy was prohibited in ancient Rome, likely well before Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. Betzig (1992), however, notes that while Roman men were legally restricted to one wife, many elite men maintained concubines and purchased slaves to breed with. On this basis, it’s argued that ‘marriage in Rome was monogamous; mating was polygynous’. However, there seems to be a bit of a motte-and-bailey going on where ‘Rome’ and ‘the Roman aristocracy’ are conflated. First, ‘Roman mating’ might have been polygynous:

But Roman mating might have been polygynous: a majority of women might have mated with a minority of men.

Then suddenly there’s a switch to polygyny in the ‘Roman aristocracy’:

The second reason to suspect polygyny in the Roman aristocracy is the comparative record.

This would by definition represent a very small percentage of the Roman population. For the majority of mating to be polygynous due to elite men’s access to sex slaves would require an arrangement more crazy than the 1:17 ratio. While slaves made up a significant portion of the population, they likely didn’t constitute a majority, and as was acknowledged in the paper, male slaves likely outnumbered female slaves. Much was said about the licentiousness of various Caesars, but disappointingly, there didn’t seem to be a serious attempt to substantiate the sensational claim that the majority of mating in Rome was polygynous.

Something else worth considering is that slaves in Ancient Greece and Rome were typically externally sourced, which would have enabled elites to practice de facto polygyny without introducing inequality among their own citizenry.

The Muslim world

Many people assume that because the Koran permits men to take up to four wives, it must be a common practice in the Muslim world. Is this true? German traveller Salomon Schweigger, writing at the end of the 16th century during his time in the Ottoman Empire, noted:

Turks rule countries and their wives rule them. Turkish women go around and enjoy themselves much more than any others. Polygamy is absent. They must have tried it but then given it up because it leads to much trouble and expense.

Another account comes from English traveller Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who visited the Ottoman Empire from 1717 to 1718 and wrote:

‘Tis true, their law permits them four wives; but there is no instance of a man of quality that makes use of this liberty, or of a woman of rank that would suffer it. When a husband happens to be inconstant, (as those things will happen) he keeps his mistress in a house apart, and visits her as privately as he can, just as it is with you. Amongst all the great men here, I only know the testerdar, (i.e. a treasurer) that keeps a number of she slaves, for his own use, (that is, on his own side of the house; for a slave once given to serve a lady, is entirely at her disposal) and he is spoke of as a libertine, or what we should call a rake, and his wife won’t see him, though she continues to live in his house.

It seems that, at least by this time, polygyny was not perceived as a high status practice.

Kurt (2013) examined the estates of 361 married men who died in and around the Ottoman city of Bursa between 1839 and 1864. Of these, 353 (97.8%) were married to one woman, 7 (1.9%) were married to two, and 1 (0.3%) was married to four. This man, the Minister of Timber in Gemlik, owned estates corresponding to 21% of the total property held by the Muslim population.

Behar (1991) analyzed 1885 and 1906 Istanbul censuses. In 1885, 2.5% of married men were polygynously married, while in 1906 it had dropped 2.2%. The intensity of this polygyny was also low, with the average number of wives per polygynous husband being 2.08. Of the 108 polygynous men in the sample, 9 had three wives, and none had four. It’s also noted that judicial records from the 16th and 17th centuries made virtually no mention of polygyny, while monogamous divorces were frequently recorded. Among men who died in 17th century Bursa and whose estates were recorded by the Kadi, fewer than 5% were polygynously married. Among the Yoruk nomads of Southeastern Anatolia, the proportion was found to be about 3%.

It seems, then, that our European travellers were reliable sources. Polygamy nonetheless faced increasing disapproval, with women being granted the right to forbid their husbands from taking a second wife in 1917, before it was outright banned in 1926.

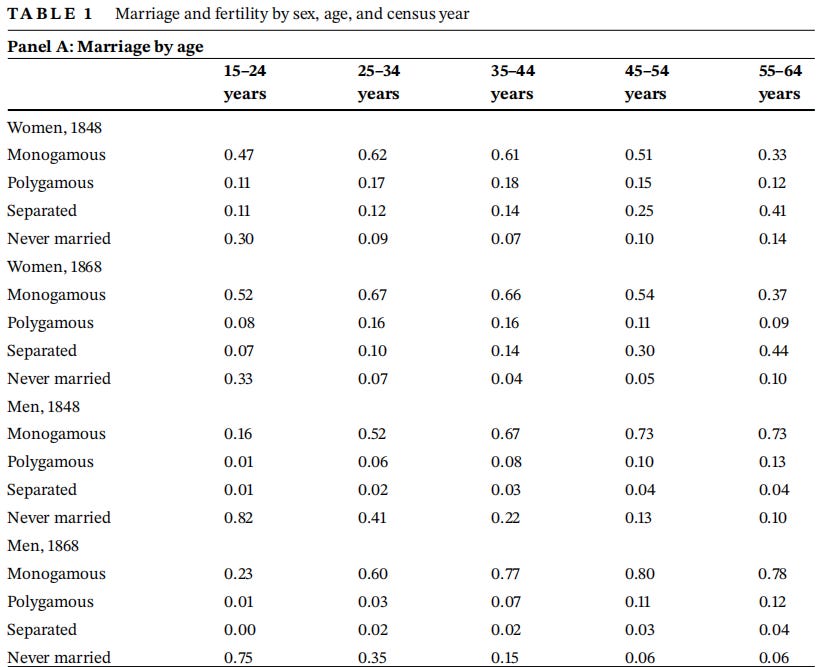

Kumon & Saleh (2023) analyzed Egyptian census data from 1848 and 1868 (h/t bored observer). The percentage of males married polygynously ranged from 1–13%, rising significantly with age. The percentage of females married polygynously was below 20% for all age groups in both censuses. Among men and women aged 45 and older, never-married rates were comparable, so while there were a lot more unmarried younger men, almost all eventually married.

Nicholson (2006) analyzed a census taken in northern and central Albania in 1918 by the occupying Austro-Hungarian army. Of extant marriages, 4.9% were recorded as polygamous, rising to 6.2% for Muslims. The rates ranged from 0.5% in the largest town to over 10% in inner mountain areas of the north, and were more common in villages than towns. Polygyny was not confined to the upper social strata; it was most prevalent in the poorest areas, and no members of the wealthiest families practiced it.

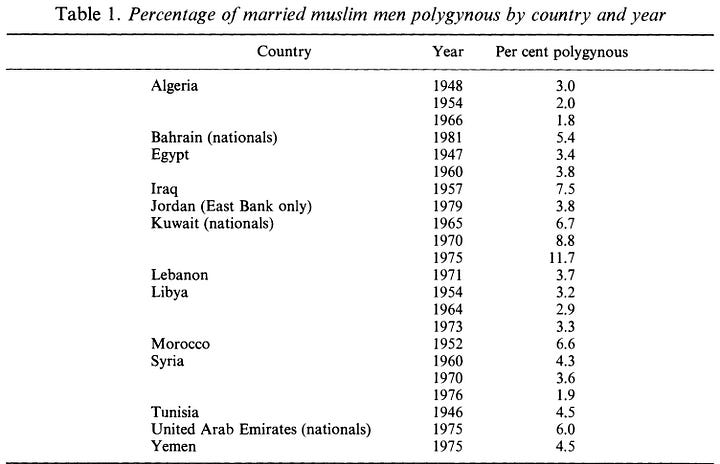

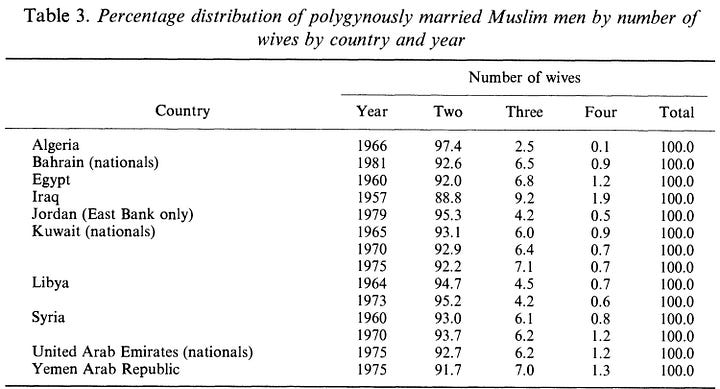

Chamie (1986) found that among married Muslim men in Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, the percentage married to multiple women between 1948 and 1981 ranged from 1.8–11.7%, with an average of around 5%. The vast majority of these men were married to only one additional wife.

The following statistics come from The Handbook of Marriage in the Arab World.

In Bahrain, 5.9% of marriages among nationals involved multiple wives in 2010, with 88.8% involving two wives. In 2015, the percentage was 5.2%, with 93.7% involving two wives.

In Qatar, 6.1% of marriages among nationals involved multiple wives in 2010, with 92.2% involving two wives. In 2015, the percentage was 8.6%, with 92.2% involving two wives.

In Kuwait, 9.9% of marriages among nationals involved multiple wives in 2010, with 88.6% involving two wives. In 2015, the percentage was 7.6%, with 89% involving two wives.

In Iraq, a law was amended in the late 1970s requiring the consent of the first wife for second marriages (which was abolished in 1993). In the 1987 census, 4% of men were married to more than one woman, mostly in rural areas.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, a 1998 survey found that 3% of married men in the West Bank were married to multiple women, while 4.4% were in the Gaza Strip. In 2016, 5.3% of marriage contracts involved men who were already married. Nearly half of women married to polygynous men had never been married before, while the other half were either widowed or divorced.

A 2009 report on Syrian families found that 6.6% of women in the countryside were married to polygynous men, compared to 4.1% in urban areas. This percentage was higher among the uneducated.

In Jordan, 8.4% of marriages between 2012 and 2016 involved multiple wives.

A 2004 Master’s thesis found that 5.9% of Libyan respondents in the city of Zawiya were polygamous.

In Yemen, 6% of married women had husbands who were married to other women. The average age gap between men and their first wives was 6.6 years, while the gap between men and their second wives was around 14 years.

A 2019 Pew Research Center report analyzed the number of people residing in various types of households in surveys from 2010–18. Fewer than 1% of Muslims in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, Algeria, and Indonesia were living in polygamous households. In Yemen and Iraq, the rate was 2%, and in Afghanistan, it was 5%.

According to the 2019 Saudi Arabia World Health Survey, 2.8% of married men aged 15+ reported having two or more wives. Among married women aged 15–49, 3.7% reported having one co-wife, and 0.3% reported having two. The polygamy rate was significantly higher among those who were older, less educated, wealthier, and more rural.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Delius & Glaser (2004) cites an account by Ludwig Alberti, who observed Xhosa communities in South Africa between 1803 and 1806. He noted that while polygyny was present among chiefs: ‘Those with least resources, must be satisfied with one woman, others have two’. A decade later, John Brownlee observed that ‘scarcely any man of common rank weds more than one wife’.

In 1850, Missionary David Livingstone collected data among the Bakaa, a Tswana chiefdom. Of 278 married men, 157 were monogamous, 94 had two wives, 25 had three, and two had four, for a polygamy rate of 43%.

Missionary David-Frédéric Ellenberger, in the second half of the nineteenth century in the Sotho kingdom, noted: ‘Among the commonality ... the percentage of polygamists was never very large, and the number of wives these allowed themselves rarely exceeded two or three’. His translator later remarked in 1912: ‘The Basuto are all polygamists in theory, but the percentage of persons with more than one wife is small and decreasing. Today it stands at about 12 percent’.

Missionary Hermann Theodor Wangemann found that while polygamy existed amongst the Pedi and the Kopa in the 1860s, ‘only the rich, the powerful and the chiefs make extensive use of it’.

By the 1950s, nearly a fifth of Xhosa women were unable to marry due to a female-biased gender ratio, partially caused by the earlier age of death for men, as well as the increasing rarity polygamy.

It’s often assumed that for any additional wife a man has, an incel is necessarily produced. However, a missionary observed how chiefs in Lesotho often took a further wife ‘with no other object than to present her to such and such of his subjects who may be too poor to buy one himself, but on condition that the latter’s children will belong to him’. Other sources suggest that some women taken as ‘junior wives’ had previously accompanied men who went on to become clients.

Missionary Martin Baumbach describes a chief with as many as 50 wives:

The women carry on with other men around here. The king knows this all along but he remains silent. Now [the real father] does not dare to come out and say that, that is my child, that would be the end of him. The king takes such a child as his child, especially when it is a girl for later he will get cattle for her.

Another account from David-Frédéric Ellenberger described how a junior wife of a chief could be ‘lent to visitors, and form intimacies of her own, as often as not with her husband's growing sons. Her children are considered to be legitimate offspring of her husband’.

This suggests that marriage was often less about sexual control, and more about control over offspring.

The Kgatla even went as far as allowing young men to channel their sexual energy by cuckolding their male relatives:

In particular, the boy's rangwane (father's younger brother) was expected to grant him this privilege... This practice so far from being regarded as adultery, was held to be highly justifiable, especially when the husband was old and impotent. The main underlying idea was that the boy should raise up seed in the junior house of his relative. My informants, however, also stressed the fact that it gave these boys the opportunity for acquiring experience which if denied them, now that they were old enough to marry, might have led to frequent attempts at seduction and other illicit means of obtaining sexual satisfaction.

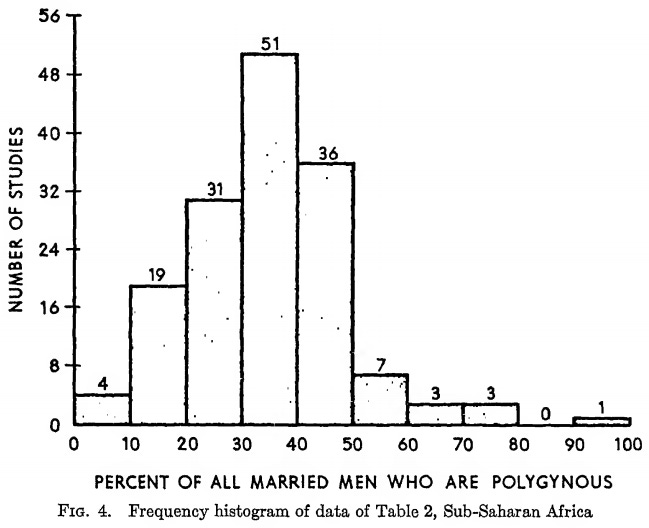

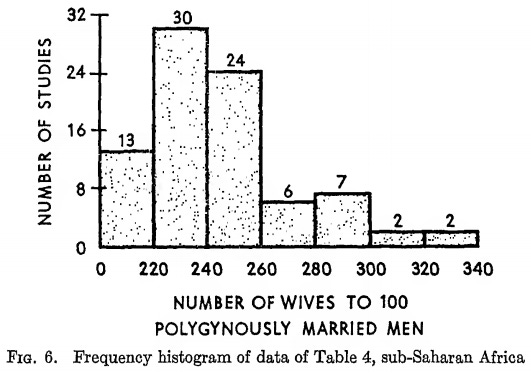

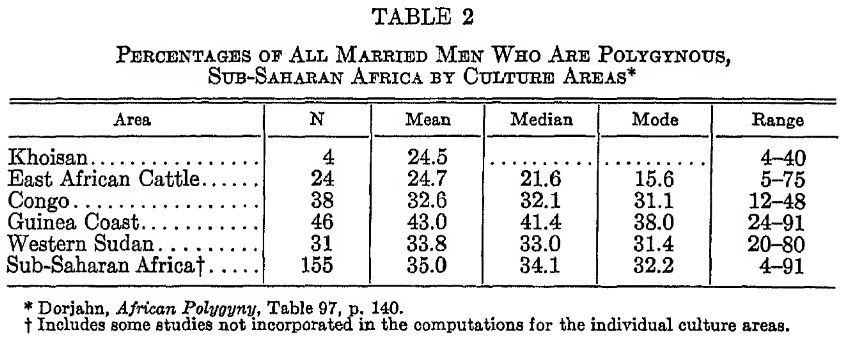

Data on various African ‘culture areas’ was collected during the first half of the 20th century. It was found that about a third of married men were married polygynously, with higher rates in West Africa compared to East Africa.

Of 136 Sub-Saharan African culture areas, about 10% met the threshold where most married men were polygynous. Per 100 polygynously married men, the average number of wives was 246.5, indicating that it wasn’t too common for them to have above two—though certainly more common than in Arab countries. Per 100 married men in general, it was 153.7, meaning three women for every two men.

Female-biased sex ratios could only partially account for this degree of polygyny. However, ‘It is not a fact, as laymen sometimes assume, that many men go through life unmarried so that a few can be polygynous’. A more relevant consideration than the overall adult sex ratio may be the sex ratio among those of marriageable age. It’s argued that since there is often a significant age gap at first marriage, this generates a larger pool of marriageable women, allowing more room for polygyny. This dynamic would be particularly pronounced in societies experiencing rapid population growth. Still, it seems without constant population growth that without the women remarrying this would still mean that polygyny would be depriving marriageable men of partners.

The 2019 Pew report revealed that 11% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa lived in polygamous arrangements, with the highest rates in West and Central Africa, where they reach as high as 36%. In South Africa though, less than 1% lived in polygamous households.

Dalton & Wilson (2014) argue that the polygyny is more common in West Africa due to a greater number of males being taken during the transatlantic slave trade, whereas more females were taken from East Africa, leading to imbalanced sex ratios. They found that the transatlantic slave trade was positively correlated with historical levels of polygyny across African ethnic groups.

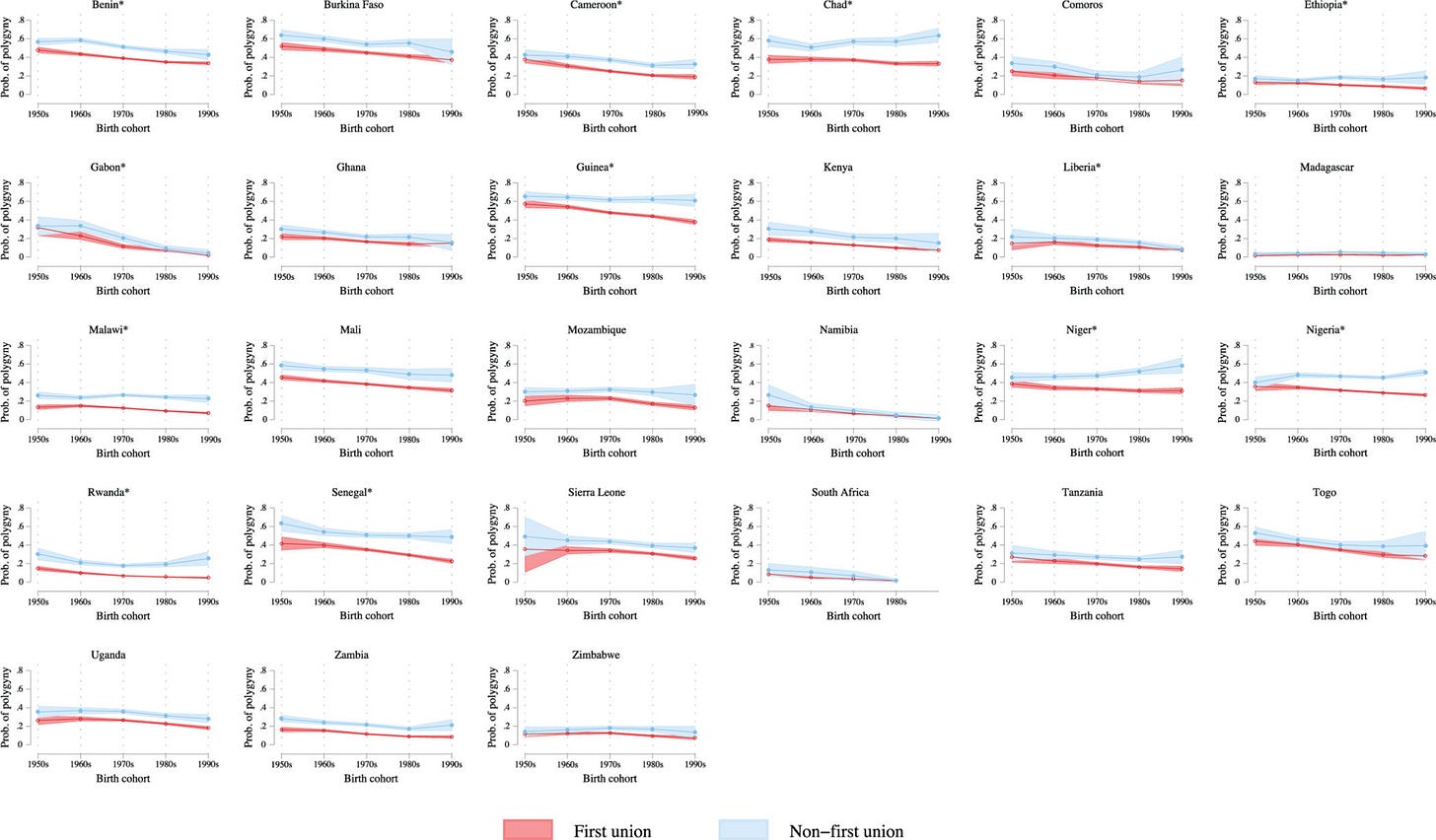

Chae & Agadjanian (2022) documented the decline in polygyny across sub-Saharan Africa using Demographic and Health Survey data from 27 countries. Women were grouped into 10-year birth cohorts, spanning from the 1940s to the 2000s.

Among currently married women, the polygyny rate declined significantly between the first and last surveys (early 1990s to the late 2010s) in all countries except Chad (goes without saying), Madagascar, and Niger. The range of decline varied from none to 68%, with a median decline of 29%, or 2% per year.

Women from younger birth cohorts were less likely to be in polygynous unions after controlling for sociodemographic, marital, and childbearing factors in all countries except Madagascar and Niger.

Women in first unions who were more educated were significantly less likely to be in polygynous unions, though there was little to no difference among women who had remarried. There was a greater selection of less educated women into polygynous unions over time.

Higher socioeconomic development as measured by HDI was associated with greater declines in polygyny.

In almost all countries, polygyny rates were higher in rural areas, and this selection also increased over time.

Extras

Polygyny rates among the general population in early modern China wouldn’t have exceeded 1–2%, with the rate being low even among elite males:

Polygyny, the marriage of one man to more than one wife, in China was largely an elite behavior. The most salient example is the Qing nobility, over one-third of whom so married. Even among the elite genealogical populations only 10 percent of male marriages were polygynous. By contrast, analysis of over 4,000 marriages among peasants in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Liaoning found polygyny rates of perhaps 1 per 1,000, while polygyny rates among early twentieth-century peasants in Taiwan were only slightly higher. Since peasants accounted for the vast majority of the population of China, it is unlikely that more than 1 or 2 percent of male marriages were polygynous.

Moreover, analysis of polygynous fertility among the Qing nobility suggests that these marriages often resembled serial monogamy, as most polygynous men slept with only one wife at a time. This suggests that polygyny may have partly served as a substitute for divorce.

In India, according to the National Family Health Survey of 2019–21, polygyny rates were 1.3% among Hindus, 1.9% among Muslims, and 1.6% among others. These rates have been falling over time, but were low to begin with.

In the 19th century US, between 8.5–12% of Mormons were married polygynously—though this varied considerably by community—and most polygynously married men had but two wives.

How common is cuckoldry?

Some might argue that even where social monogamy is the norm, actual mating may be less monogamous. We’ve already mentioned how some monogamously married elite men kept female slaves to breed. Another mechanism for non-monogamous mating within ostensibly monogamous unions is of course cuckoldry. This is well-documented in birds, where many socially monogamous species nonetheless exhibit high rates of extrapair paternity (EPP), typically around 20%.

Fearmongering around this topic is rampant online. Alarmingly high figures are frequently cited, with as many as one in three men reportedly unwittingly raising offspring sired by another man. Such figures are based on paternity test results, however. It doesn’t take a genius to realize that men who go out of their way to confirm paternity—usually due to suspicions of infidelity or doubts about physical resemblance—constitute a highly biased sample.

So, what do studies using more representative samples find?

Anderson (2006) reviewed 67 studies and found a median EPP rate of 1.7% among men with high paternity confidence, compared to 29.8% in low-confidence samples (e.g., paternity testing clients). When the methodology is unknown, it was 16.7%, and combining this with the high confidence sample gives a median of 3.3%. Of course, this varied by location and group; for instance, US blacks had higher rates than US whites, and the Yanomamo of Brazil/Venezuela had a relatively high rate of 9%.

Strassmann et al. (2012) analyzed genetic data of 1,706 father-son pairs in a traditional African population and found EPP rates of 1.3% among adherents of an indigenous religion 2.9% among others. All practiced cultural norms discouraging extrapair sex, but the indigenous group also had a menstruation-signaling system which may have promoted paternity certainty.

Wolf et al. (2012) studied 971 German children and their parents, using HLA haplotypes, revealing a nonpaternity rate of 0.9%.

A number of studies have also estimated historical EPP rates by identifying Y-chromosome mismatches between individuals whose genealogical records indicate they share a common paternal ancestor. These are the results.

Larmuseau et al. (2013): 0.9–2% per generation over the past 400 years among Belgians.

Boattini et al. (2015): 1.2% per generation over the past 400 years among Northern Italians.

Greeff & Erasmus (2015): 0.9% per generation over the past 300 years among Afrikaners.

Solé-Morata et al. (2015): 1.5–2.6% per generation over the past 500 years among Catalans.

Larmuseau et al. (2017): 1% per generation over the past 400 years among the Dutch.

Larmuseau et al. (2019): 0.4–5.9% per generation over the past 500 years in the Low Countries.

One major outlier bears mentioning: Scelza et al. (2020) found an unprecedentedly high EPP rate of 48% among Himba pastoralists in northern Namibia, with 70% of couples with children having at least one child sired by another man. This probably shouldn’t be considered ‘cuckoldry’ per se, as I believe the way this figure was derived is simply by counting children from past relationships as the products of cuckoldry—an earlier study by the same author found a rate of 17%, all within arranged marriages. Also, it’s a socially sanctioned practice within their society; cultural norms expect men to invest equally in biological and non-biological children. Reflecting this, Himba men were accurate in their non-paternity suspicions 70% of the time compared to the usual rate of 30%.

Do women want polygyny?

There are two main families of polygyny models: those focused on female choice and those focused on coercion. The first suggests that women may choose already-married men when there is significant variation in men’s ability to monopolize or defend resources. In such cases, married men—and potentially co-wives, especially if they’re sisters—may offer greater material security, theoretically leading to higher reproductive success. The second suggests that polygyny is generally not adaptive for women, and that given freedom of choice, they would typically avoid it.

One challenge for those who attribute polygyny to female choice is explaining why polygyny is most prevalent in the societies which are most patriarchal, while it becomes rarer as women are granted greater autonomy.

The banning of polygamy in countries such as Turkey, Tunisia, and Albania has been attributed in part to the influence of women's rights movements, which gained momentum during the late Ottoman Empire. This female opposition to polygamy continues in the Muslim world today. A survey in India found that 92% of Muslim women supported a polygamy ban, which recently went through. Similarly, a poll in Iran found that 96% of women opposed men taking a second wife. A controversial bill that would have allowed men to take a second wife without the first wife’s consent was met with widespread protests from women’s rights activists, and ultimately failed to pass. Additionally, a survey by Thomas et al. (2022) of 393 UK residents found that only 5% of women were open to a polygynous relationship, compared to 39% of men.

Sure, they might be thinking from the perspective of the first wife, but if the previous data says anything about women’s revealed preferences, few wish to become the second either in the vast majority of cases.

Larsen (2023) cites an anecdote about 70% of female students reportedly stating they’d prefer to be the second wives of a billionaire rather than the exclusive wives of an average man.

Both agreed that our evolved psychology biases people to polygyny, but Henrich thought that by legalizing such pair-bonds, we risked a rapid transformation of Western societies. In repeated surveys of his undergrads, he had found that 70% of females would prefer being the second wife of a billionaire rather than the exclusive wife of an average man (BCSC 1588, 2011). Since women are so drawn to marrying up, polygyny may not remain a niche mating strategy, but spread to the majority population.

The way I see it, it’s telling that such an extreme and unrealistic hypothetical is needed to get most women to say they’d prefer polygyny. There are plenty of unpleasant things people might claim they’d do in exchange for access to a billionaire’s wealth. I wouldn’t be surprised if many heterosexual men would say they’d become a boy toy for a gay billionaire over being with an average woman, too.

Marlowe (2003) found that in the 186 SCCS societies, arranged marriages were correlated with polygyny prevalence (r = .5), but only when female marriages were arranged, providing support the coercion model. Additionally, assault frequency strongly correlated with the percentage of polygynously married women (r = .67).

Did Genghis Khan’s wives and concubines flock to him because he was a high value alpha male? Let’s take a look at the list:

Börte: Genghis Khan’s first wife, betrothed to him in an arranged marriage to solidify alliances between their respective clans.

Yesugen: Taken as a wife after the defeat of her tribe, the Tatars.

Yesui: Kidnapped at the recommendation of her younger sister, possibly as part of a political strategy.

Khulan: Offered as a wife by the Merkit leader after his surrender, as part of an alliance.

Möge Khatun: Given as a wife by a chief of the Bakrin tribe, likely to strengthen relations.

Juerbiesu: Taken as a wife during the conquest of the Naiman.

Ibaqa Beki: Given as a wife by a Kerait leader to strengthen political alliances.

Chaka: Given in submission to Mongol rule during the campaign against Western Xia.

Qiguo: Married in exchange for his relief of the Mongol siege upon Zhongdu during the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty.

Most of them appear to have either been forcibly captured or given in diplomatic exchanges to strengthen alliances or consolidate power. Consorts of most kings and emperors throughout history, such as the sultans of the Ottoman Empire, were also typically a mix of arranged marriages and enslaved women. An example from Ottoman Empire founder Osman I: ‘Fülane Hatun. Girl from humble social background with whom Osman became infatuated when he was very young. When she rejected his marriage proposal, believing it to be a joke, Osman kidnapped her and made her his concubine’.

McMahon (2013) describes how a Chinese emperor would send people to induct women into his harem, prompting many families to hastily marry off their daughters in advance:

It was common for emperors to embellish their image as polygamists. They knew that others were watching, especially their officials and the imperial wives, mothers, and grandmothers. In another example of self-embellishment, in 273 Jin Emperor Wu launched an empire-wide selection of women for his harem. Since women entering the palace tended never to see their families again, families were known to react to such searches by hurriedly marrying off their daughters to avoid selection. To stem this tendency, the emperor prohibited marriage throughout the empire while the recruitment took place, then followed with two exemplary acts of polygamous propriety. First, he proclaimed that he would never enthrone a concubine as empress and, second, that he would submit all choices to his empress, who reportedly weeded out the exceptionally beautiful ones.

Polygyny has been linked to warfare for plunder and the capture of female slaves. This raises a chicken-or-egg dilemma: Does polygyny lead to violence, or does violence lead to polygyny? An article quoted earlier also recounts a story of a Viking chieftain who had 40 concubines, while his favoured 400 warriors were each granted multiple slave girls, arguing that this left the vast majority of Viking men without mates:

The Islamic explorer Ibn Fadlan described a Viking chieftain who had 40 slave girls that “were destined for his bed,” while his 400 warriors were given two slave girls each, in addition to their other wives.

But if Viking chiefs had 40-plus concubines and wives, and his favored warriors had an additional four or five women each as well, then where did that leave the vast majority of Viking men who wanted a mate? It left them on a Viking longship headed towards an Irish village where they could capture a woman and sell her husband off into slavery.

This argument assumes that these ‘slave girls’ were drawn from the local population. As it mentions however, they would capture them during raids, so it’s far from obvious that widespread polygyny pre-dated these raids.

High male mortality rate in warfare is predictably associated with both an imbalanced sex ratio and polygyny. Historically, the destruction of large numbers of men in war left many widows and orphans in need of provision and protection. Friends or relatives of widowed women would take them under their wing. The practice of polygyny would also aid in rejuvenating the population. Heinrich Himmler and Martin Bormann reportedly envisioned polygyny as a solution to the surplus of women in post-war Germany. An interesting case study is Syria, where following the outbreak of the civil war, polygamy rates shot up dramatically, going from a rate of 5% of marriages registered as polygamous in the capital in 2010 to 30% in 2015.

A study by Gaddy et al. (2024) presents a compelling case against the narrative that polygyny causes war by depriving men of partners. According to this narrative, greater polygyny increases the pool of unmarried men, leading to greater risk-taking and status-seeking behaviour in efforts to secure a wife. When comparing the proportion of married men over 20 in polygynous marriages with the proportion of never-married men in their 20s, only 6 out of 74 subnational enumerations showed polygyny predicting more never-married men at the subnational level, while in 34 enumerations polygyny predicted fewer men having never married. An analysis of 1880s Mormon communities in Utah likewise revealed that the polygynous counties had fewer never-married men in their 20s than the national average.

Clearly, polygyny itself doesn’t enable more men to marry, so what’s going on? Controlling for local sex ratios explained only a quarter of the negative association between polygyny and never-married men. The authors suggest that stronger marriage and pronatalist norms in polygynous communities provides a better explanation for these findings.

Polygamy also tends to be inversely correlated with women’s education—not only at the national level, but also within countries and across time, as seen in the study on the decline of African polygyny. The practice has become increasingly relegated to more rural and traditional segments of society. Women’s emancipation likely plays a large role in this decline: As both the number of men with strong job prospects and the number of women dependent on financial provision decrease, polygyny becomes a less tolerable option. Another contributing factor is likely that additional wives didn’t just serve to satisfy sexual lust, but were also valued as economic assets, with women contributing to agricultural production in societies predicting a higher rate of polygyny. With the transition to more service-based economies, there is less demand for this.

Research on whether polygyny enhances women’s reproductive success is mixed, but much of it suggests that it may actually reduce it. For instance, Chisholm & Burback (1991) found that women in an Australian Aboriginal community who spent their reproductive years in monogamous unions had higher reproductive success than those in polygynous ones—running counter to a core prediction of the female choice model.

There is potential evidence for the female choice model in the association between polygyny and pathogen stress (e.g., Marlowe, 2003), as it has been hypothesized that women shift their preferences towards ‘good genes’ in high-pathogen environments. However, studies have largely failed to detect meaningful relationships between markers of immune system function—such as genomic heterozygosity—and attractiveness, which calls into question the assumption that female choice for more physically attractive partners mediates this. Obviously there aren't zero cases where women exercised agency in joining a polygynous union, but they’d typically have needed a very good reason for doing so.

Conclusion

Genetic studies have revealed that men's genetic diversity tends to be lower than women's, a fact many have interpreted as evidence of widespread polygyny in human history. We explored alternative mechanisms that could explain this lower diversity: sex-biased migration patterns associated with patrilocal residence systems, genocide of groups where genetically related men were clustered due to patrilineal kinship, the spread of high-status male lineages over time through the intergenerational transmission of reproductive success, and purifying selection. Lineal fission—the division of a group into subgroups based on shared paternal ancestry—may have helped to accelerate the process. Importantly, several of these mechanisms provide what I’d consider more reasonable explanations for the Neolithic bottleneck. Not only because a reproductive ratio of 1:17 doesn’t pass the sniff test, but because they align with the timing of the bottleneck, which began after the agricultural revolution and ended with the rise of more complex states.

There are also several facts that don’t align with the mass harems explanation. For one, the bottleneck ended with the rise of more complex states, despite a corresponding increase in social and material inequality. Among non-industrial societies, agriculturalists don’t practice more polygyny or exhibit higher reproductive skew. Studies of ancient DNA from archaeological sites show evidence for patrilineaty and patrilocality, but few signs of polygyny, with half-siblings being relatively scarce. Cuckoldry has not been a widespread phenomenon, even before the advent of modern contraception.

While polygyny has been present in many societies, its scope is generally limited. Despite being generally permitted in the Middle East and North Africa, polygyny is rarely practiced. Although higher rates of polygyny are seen in Central and West Africa, as well as among many non-industrial societies, they fall far short of the levels required to explain the Neolithic bottleneck or even the overall lower Y-DNA diversity compared to mtDNA observed outside that period. This cross-sectional data only tells half the story, too. Polygynous unions tend to be less stable than monogamous ones, meaning the actual time spent in polygynous versus monogamous unions is lower than the raw figures suggest. Also, a significant portion of women who marry already married men have previously been divorced or widowed. In Chamie (1986) for example, among Egyptian brides, only 3.7% of those marrying for the first time married a currently married groom, compared to 32.6% of widowed and 22.5% of divorced brides. For Jordan, the figures were 5.3%, 35.4%, and 28.1%, respectively.

All that aside, the assumption that polygyny is primarily driven by women’s preferences is questionable given its association with arranged marriage and the issue of jealousy, and war has probably been a significant driver.

I debated whether to include a section on hominin sexual dimorphism, but the fragmentary nature of the fossil record and the fact that low dimorphism doesn’t necessarily imply monogamy make this a tenuous business. The most you can say is that strong sexual dimorphism indicates intrasexual competition among males. Nonetheless, among primates, humans are on the low end of the sexual dimorphism scale, with males averaging about 1.15 the size of females, compared to gorillas wherein the males are about twice as large. There also appears to have been a general decline in body size dimorphism since Australopithecus a few million years ago.

Human mating systems are uniquely flexible due to considerable cultural and genetic diversity, posing a challenge for straightforward categorization. However, despite some mild polygynous tendencies, the system that appears most persistent across space and time is serial monogamy: long-term pair bonding with significant parental investment and occasional partner switching and infidelity. The theoretical basis for this I can’t do justice to here, but a key factor likely lies in humans’ unusually long developmental period, primarily due to big and complex brains—most of whose development must happen outside the womb, creating a strong incentive for biparental care.

For many men, of course, there’s a testosterone-fueled desire to pursue sexual relationships with multiple women, and when they were in the privileged position of having their every desire fulfilled, they did so. Examples such as King Solomon—who is said to have amassed a harem of 700 wives and 300 concubines—are often brought up in discussions of polygyny. However, it would clearly be silly to base our conception of how most people have lived throughout history on the extravagant lives of the top 0.0001% while overlooking the existence of the nameless non-elite masses who likely lived monogamously. The impact of these elite men hoarding large numbers of women would have had at best a minimal impact on society at large, especially since many women were taken captive.

People who buy into the historical mass polygyny narrative also tend to think this is playing out today—just in a more ‘covert’ manner. The Chadspiracy, as I sometimes call it. If mass polygynous mating were ever going to emerge, it would likely be in a society where sexual mores have crumbled and women were free to mate however they pleased. Yet, even in such a society, we see a remarkable degree of egalitarianism in sexual outcomes between the sexes, with heterosexual promiscuity remaining confined to a small minority of men and women. Many assume that because it’s easier for women to engage in casual sex, they are, but the simple reason it’s so much easier in the first place is that they generally have little desire for it—a fact everyone seemed to recognize until recently.

It might not be the most exciting or subversive conclusion, and some may wish to believe otherwise—whether they be incels or genderfluid polyamorists—but rather than needing to be imposed from the top down, monogamy appears to be for the most part self-enforcing, and has likely been the norm long before Christianity or civilization came onto the scene.

It bears repeating that the Neolithic bottleneck does not demonstrate that 95% of men were sexless, nor does it mean that 95% were killed off. Rather, it likely reflects the elimination or gradual whittling down of weaker or less fortunate male lineages, which prevented many from making it to the other side. Of course, it may never be possible to definitively prove what happened, and it’s likely that more than one explanation is involved. At the end of the day it’s up to you to decide what seems most plausible in light of the available evidence, as limited as it may be. Whatever the case, history has by no means been an egalitarian paradise; it has largely been an unforgiving game of survival of the fittest, widespread polygyny or otherwise.

It appears to have since been removed from YouTube.

I would add to this discussion the hypothesis that primogeniture as a historical practice maximized the mating potential of the first-born son. If the wealth were divided amongst all the sons (say there were 2 sons), each son would have half the mating potential. Assume a threshold of mating potential, like if a man inherits less than $10k he doesn't breed. Pooling all the resources for the first born son is an extremely effective way of ensuring that the line continues. Traditions which practiced primogeniture would genetically outcompete (in Y-DNA at least) traditions which did not.

Primogeniture fortified certain Y-DNA lines with this particular culture practice. Assuming an unbroken line of paternity, primogeniture would end up producing a mating arrangement where a few dudes (Charlemagne, Genghis Khan, Mohammed, Abraham, "Zeus", "Odin," etc) would appear to be the only men to have bred at all. This doesn't require polygamy -- merely that the first-born son has his breeding potential maximized through inheritance.

This is one of those topics where I think this article would serve as a great script for a video essay. I'm just getting into the topic now so still learning and correcting my preconceived chadopoloy notions.

The “rapidly growing population” case is interesting. Assuming for arguments sake roughly equal numbers of male & female children surviving to adulthood but that females marry approximately 5 years younger, a growing population would indeed result in a surplus of marriageable women whereas a stable population would not