For many online, self-reported sex data is problematic, as it doesn’t jibe with their preconceived notions of the sexual marketplace. It fails to reveal as many incels or 304s as they had imagined or hoped to see, and refuses to confirm the Chadopoly that’s become conventional wisdom. Instead, it cuts through the memes, painting a more mundane picture wherein a solid majority of young men and women report zero or one partner over the past year, with promiscuity confined to a small minority of both genders.

They want to see this:

But the reality looks more like this:

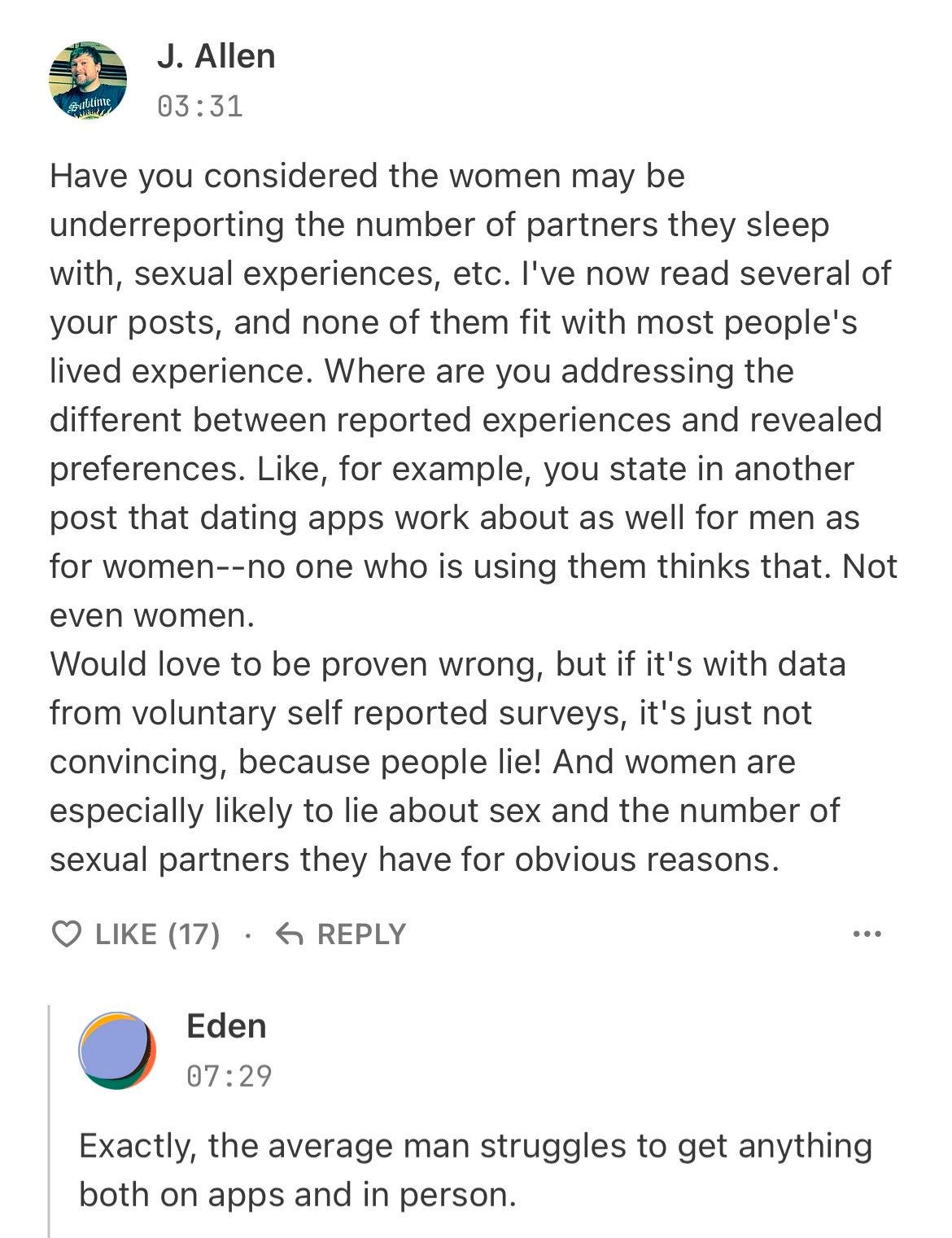

Unsurprisingly, this leads many to reject the data. How? The most common move is to just say it’s all lies. The men are too ashamed to admit they’re incels; the women are too ashamed to admit they’re 304s. In the comment below, we see an appeal to lived experience as the superior epistemology.

In no article by the way will you find it stated or even implied that dating apps work just as well for men. The trivial fact that dating apps don’t work well for many men was explicitly acknowledged in the main article on the topic, but apparently that wasn’t enough. What I’ve pointed out is that actual outcomes such as dates and sexual encounters don’t show the gender imbalance (on the population level) that everyone believes is somehow an inevitable corollary, and I’ve tried to address the confusion they experience when trying to reconcile these facts, but it simply does not require men and women to make an equally high percentage of right swipes or an equally high chance of matching with those they they swipe right on.

I’ve also pointed out that once you adjust for the gender ratio—which is necessary when there are around three times as many men using dating apps, inflating the average number of matches for women relative to men—the median number of matches men get per day is the same as that for women, rather than the average woman far outmatching the average man as would be expected if they were routinely matching with Chads. This is also highly counterintuitive to people, as they wrongly assume potential matches are effectively equivalent to actual matches. Again, nothing about this implies that dating apps work ‘just about as well for men’—this is either a disingenuous or lazy misreading of what was actually being said. This is hardly surprising though; people are naturally disinterested in a fuller understanding of what’s going on and prefer to vent their frustration and righteous anger about things which frustrate and anger them. Anyway, I didn’t want to rehash everything there, nor do I want to here. You can see the actual arguments and evidence here.

Sadly, I’m not hopeful that this individual or anyone else who agreed with this sentiment are the rare exceptions genuinely eager to have their mind changed. But since previous analyses have often leaned heavily on self-reported sex data, and since rejecting the validity of such data out of hand is the default cop-out, a justification for taking the numbers seriously is probably in order

Is this a real issue?

First, some simple a priori reasoning. The fact that male and female sexual partner distributions mirror each other as closely as they do across various datasets lends face validity to the reports. For this to be the case despite a theoretically high level of gender asymmetry would require misreporting of just the right amount across the whole distribution, which stretches plausibility.

Moreover, the standard assumption isn’t just that women underreport, but that men exaggerate. The implication of this is that men’s reported average becomes a hard ceiling on overall sexual activity. If young men report an average of 1.5 partners in the past year, little room is left for widespread promiscuity among young women. To maintain this belief, you must also believe that men are underreporting—contradicting the initial premise.

GSS data on opposite-sex sex partners since 18 among men aged 25–39 shows no evidence for rising promiscuity,1 with the mean having returned to about 12 partners (where it was in 1989). Of course, the mean is heavily skewed by the right tail, and the median is about half that. For 20–24 year old men, the mean is 6 partners (5 if you set the cap to 50), and this is not rising either.

As noted in the previous article, reporting bias is only relevant to trend analysis insofar as there are trends in the bias itself. For instance, if women's partner counts aren’t rising, to attribute it to bias you have to assume women are facing growing pressure to underreport—presumably because society has become increasingly puritanical, which seems like a difficult case to make. Otherwise, if for example women reported only half of their partners, we’d still expect to see a rise in promiscuity if there were one, just attenuated. In the above example, you’d have to assume that men are now less inclined to exaggerate, but I don’t see a good reason to think that either.

That said, what’s true is as with most self-reported data, sex partner data isn’t perfect. A simple way to demonstrate this is to look at the partner counts reported by men and women, where men report a significantly higher number—especially when asked about longer time periods.2

It’s often said that in a closed population, the number of opposite-sex partners reported by men and women must be equal. While this is more or less true, we could nitpick and point out that the gender ratio isn’t perfectly balanced overall or within age groups, which affects the averages. The overall female average is dragged down by a surplus of older women, who tend to report fewer partners. Moreover, the population isn’t completely closed—migration flows further skew the balance. Nonetheless, adjusting for these factors is unlikely to put a huge dent in the discrepancy.

Explaining the discrepancy

First off, credit to Date Psychology, who has already done a solid article on this question, which covered some of the studies discussed below.

Social desirability bias

Social desirability bias refers to the tendency for individuals to answer questions in ways they believe conform to social norms. This phenomenon underpins the ‘men lie up, women lie down’ idea, as it’s based on the assumption that people respond this way because sexual promiscuity signals status in men but is stigmatised in women.

Meston et al. (1998) assessed the influence of two distinct types of socially desirable reporting: self-deceptive enhancement and impression management. The former reflects a tendency to offer honest but unconsciously inflated self-descriptions; the latter reflects a more deliberate effort to present oneself in a socially favourable light.

After correcting for multiple comparisons, self-deceptive enhancement correlated with just 2 of the 21 sexuality items: sexual competence and positive body image. Both became nonsignificant after controlling for the Big Five and conservatism. Impression management had more relevance, correlating positively with age of first sexual foreplay and virginity status, and negatively with variety of sexual experience, unrestricted sexual behavior,3 variety of sexual fantasy, liberal sexual attitudes, unrestricted sexual attitudes and fantasies, and subjective sexual drive. Controlling for the Big Five and conservatism rendered only some of these correlations nonsignificant.

For men, self-deceptive enhancement correlated only with sexual satisfaction, while impression management correlated negatively with unrestricted sexual attitudes & fantasies. It’s worth mentioning that one of the items was virginity status, as it’s often claimed that many men in surveys lie about this.

These correlations were small overall, indicating that the vast majority of variance in self-reports isn’t driven by social desirability bias. It’s also interesting how the effects tended to point in the same direction across genders.

Gibson et al. (1999) administered a 20-item short form of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale to 508 participants entering heroin detoxification treatment programs. Social desirability scores were divided into quartiles. Those scoring higher on social desirability reported less injection behaviour in the past month, while sexual behaviour showed no significant associations. Correlations between behaviours and social desirability differed little by gender, with differences of .1 or less.

Turchik & Garske (2009) employed the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and the Sexual Self-Disclosure Scale with a sample of 613 undergrads. The MCSD showed no significant correlation with any of the five sexual risk-taking scales, while the SSDS correlated negatively with impulsive sexual behaviour, risky sex acts, and intent to engage in risky sexual behaviours, with coefficients between –.11 and –.13. Men and women reported risky and taboo sexual acts at virtually the same rate; however, when limiting the sample to individuals reporting ten or more partners, this is when significant gender discrepancies emerged.

Rao et al. (2017) analysed data from 559 participants who reported having a recent sexual partner during their 6-month visit in a longitudinal study of heroin and crack users. Having more than one sex partner in the past six months was negatively associated with scores on a 10-item social desirability bias scale for women, though this effect was modest and barely passed the p < 0.05 threshold.

Weber et al. (2025) recruited about 3,000 UK participants from an online crowdsourcing platform. They utilised the item sum technique—an indirect questioning method which involves participants in one group receiving a sensitive question embedded between two non-sensitive questions, such as the last two digits of a friend’s phone number, and reporting only the total sum of their answers. Researchers then compute mean estimates for the sensitive question by subtracting the average sum of the non-sensitive questions from the average total. These estimates are compared with the mean of direct responses to detect systematic reporting bias.

When examining the ‘sexual motivation’ variables—sexual fantasies, desire, and self-stimulation—both genders reported higher levels in the IS group, but the only significant group effect was for male fantasies, and the gender differences remained virtually the same across groups.

There was also no difference in the number of sex partners between the DQ and IS groups, with men and women in both reporting an average of about six partners. The absence of a significant gender difference in reported partner counts may reflect the increased anonymity afforded by the online survey. They were also reminded of their anonymity and the importance of answering honestly.

Men reported a higher frequency of sexual intercourse in the DQ group. This difference lost significance after correcting for multiple comparisons, but there was a significant a Group × Gender interaction due to the effect being slightly reversed in the IS group.

Social desirability scales were also administered to the DQ group. No significant correlations emerged for the sexual motivation indicators. Correlations with sexual intercourse frequency and number of partners were also small and generally nonsignificant. There does seem to be a significant correlation between self-deceptive enhancement and sexual partners among men (r = .15) that with a sample size of 538 would still be significant after correction for multiple comparisons.4

Similarly, Date Psychology cites a couple of studies showing men’s higher reported partner counts were mediated by their tendency to associate status more closely with promiscuity, and also reports his findings that perceiving promiscuity as status-enhancing correlates with higher self-reported partner counts.5

The bogus pipeline

Another method devised to reduce socially desirable responding is the bogus pipeline experiment, whereby participants are hooked up to what they are led to believe is a lie detector and asked sensitive questions. Responses obtained under this condition can then be compared to others to infer whether people are in fact fibbing. Of course even ‘real’ lie detectors are of highly questionable reliability—but all that matters is that people think they work. Even today, more people trust their accuracy than doubt it.

Date Psychology wrote about the bogus pipeline, citing a study where men were 6.5 times more likely to admit to illegal sexual assault under the bogus pipeline condition. Additionally, a meta-analysis revealed generally medium effect sizes across various research areas, suggesting this method is quite effective at eliciting more honest responses.

Tourangeau et al. (1997) used this method and found significant differences in a several substance use questions and exercising frequency. Among the five sexual behaviour questions, only frequent oral sex showed a significant difference, with participants in the bogus pipeline condition reporting it more than those in face-to-face interviews.

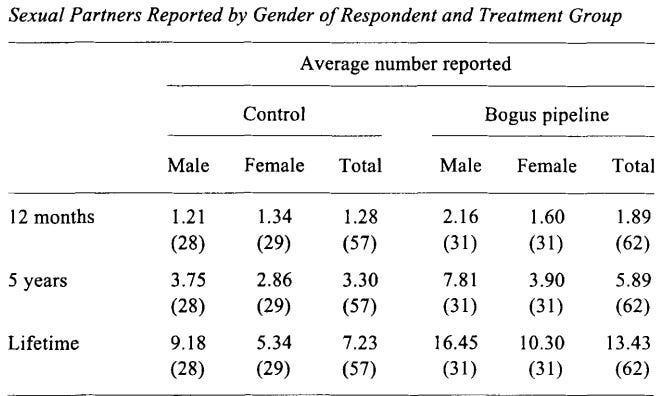

Both men and women reported more partners in the past year, past five years, and lifetime under the bogus pipeline condition, but these increases weren’t statistically significant. It was quite a few more too—86% more lifetime partners in the bogus pipeline condition—but the sample sizes weren’t sufficient for significance.

The big study frequently cited by naysayers is Alexander & Fisher (2003). They assigned 201 undergrads to one of three conditions: an anonymous paper survey, a bogus pipeline, or an exposure threat condition, where participants believed their answers would be revealed to the experimenter.

There was an effect of testing condition on erotophilic attitudes, with those in the bogus pipeline condition scoring higher than those in the exposure threat condition; however, there was no interaction effect between gender and testing condition. No significant differences emerged for attitudes towards sexuality or for sexual experience (whether people have engaged in a variety of sexual acts).

The gender difference in the composite score for autonomous sexual behaviours was greatest in the exposure threat condition. There were some marginally significant effects for age of first consensual intercourse—men reported a higher age than women in the anonymous condition, and there was a significant effect of testing condition for women—but no straightforward pattern emerged.

Now we come to the point of controversy: mean number of sexual partners. It turns out that although there was a clear progression from exposure threat to pipeline conditions, the authors report that ‘The two-way ANOVA on self-reports of the number of sexual partners yielded no significant effects, F < 1, but the data did strongly favor the predicted pattern’. Women’s reported partner count was 30% higher in the bogus pipeline condition compared to the anonymous one—not exactly earth-shattering regardless.

A similar study by Fisher (2013) found no main effect of condition for either men or women, but did observe a significant interaction whereby women in the bogus pipeline condition actually reported significantly more partners than men.6 At the same time, women’s average lifetime partner count only rose by 0.65, or 25%.

No effect of testing condition emerged for age at first intercourse or number of one-time partners, however.

In another study, Fisher & Brunell (2014) found that men scored higher than women on extradyadic behaviour in the anonymous condition, but no significant gender differences appeared in the exposure threat or bogus pipeline conditions, nor differences across these conditions.

Counting strategies and missing prostitutes

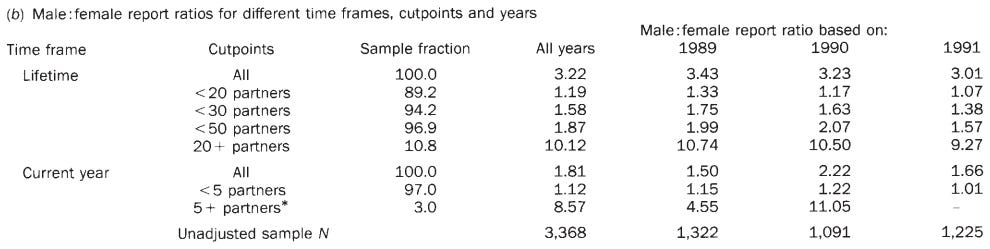

Morris (1993) observed that average partner counts were skewed by a small subset of men reporting extreme numbers. After excluding the 10% of respondents reporting 20 or more lifetime partners, the male-to-female ratio dropped from 3.2:1 to 1.2:1.

Wiederman (1997) analysed the same GSS dataset and identified a tendency for respondents to favour round numbers such as 30 and 50. It was also found that removing respondents who reported engaging in prostitution reduced the gender discrepancy somewhat.

In a separate study of 324 college students, correcting for the campus gender ratio somewhat reduced the gender discrepancy, while adjusting for self-reported recall accuracy fully eliminated it. Twice as many men as women reported a low level of accuracy.

Brown & Sinclair (1999) found that 29.4% of male responses were rough estimates, compared to just 4.4% of female responses. Meanwhile, 48.9% of women reported using an enumeration strategy—specifically counting each person they’d slept with—compared to 29.4% of men. Among those who used the same estimation strategy, no statistically significant gender difference was found.

Brewer et al. (2000) argued that prostitutes were undersampled in national surveys. After factoring in their estimates for the prevalence of prostitutes and their partner numbers, the discrepancy in reported partner counts between heterosexual men and women over the past year and five years was eliminated.

Mitchell et al. (2019) analysed data from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. Men reported a mean of 14.14 lifetime partners; women reported 7.12. The gender gap of 7.02 reduced to 5.47 after capping lifetime partner counts at the 99th percentile. Adjusting for counting versus estimation reduced it further to 3.24, and a subsequent adjustment for sexual attitudes narrowed it to 2.63. Together, these factors may account for roughly two-thirds of the disparity.

Sampling explanations such as inclusion of non-U.K.-resident partners and underrepresentation of prostitutes had only modest effects. Contrary to common belief, men were actually more likely than women to exclude oral-sex-only partners from their totals, so this didn’t help explain the gap. The authors also note that the attitude measures were relatively limited proxies for adherence to gender norms and may have underestimated the magnitude of this factor.

Conclusion

Claims that self-reported sex data is imperfect aren’t completely unfounded, but that doesn’t justify throwing the baby out with the bathwater. When it comes to average lifetime partners, men’s average is inflated significantly by a subset of men claiming to get around like the Beach Boys. When disregarding outliers or focusing on narrower time frames, the discrepancy is significantly attenuated.

Past-year sex partner data, like that seen in the second graph in the intro, is probably quite accurate. I couldn’t find the right place to insert this, but Jaccard et al. (2004) surveyed 285 single young heterosexuals weekly, asking how many sex partners they’d encountered that week, followed by initials and a few identifying questions to track continuity. These weekly records were then compared to participants’ longer-term recollections.

They found a reasonable degree of accuracy—though it began to fall off after the first partner. No correlation emerged between gender and report accuracy in either abstainers, monogamists, or those claiming multiple partners. Among the latter, large discrepancies were rare: depending on the time frame, 82–95% were within one partner. At 12 months, those reporting multiple partners were off by about one partner on average, and self-reports and actual encounters correlated at .7.

We explored the impact of social desirability bias on self-reported sex data, by examining correlations with dedicated scales and through bogus pipeline experiments. The results were somewhat mixed: in both cases, effects were either absent or small. Overall, it’s hard to say whether the bias, if present, is more due to men exaggerating their sexual experience or women downplaying theirs—there’s at least some minor evidence pointing in both directions. Stronger and more consistent effects tend to show up in other domains like drug use.

It’s worth noting however that social desirability bias scales are not without their critics. Some argue they index personality traits that genuinely influence behaviour, and a meta-analysis found a near-zero correlation between SD scores and prosocial behaviour in economic games, which they argue casts doubt on whether these scales meaningfully capture either bias or ‘substantive traits’. But they seem to be measuring something, at least.

Other factors could also play a role, including men being more comfortable with guesstimating and the undersampling of prostitutes in surveys—though maybe not to the extent that some have suggested.

The fact that the gap seems to be closing over time7 suggests that social desirability probably has played a role, and that the influence of the ‘sexual double standard’ has been waning.

Regardless, as outlined earlier, this is largely a red herring. You can’t invoke reporting bias to explain away a trend or lack thereof without making a case for a parallel trend in reporting bias, and the gap between men and women’s average partner counts isn’t large enough to support the idea that women are drastically underreporting and all secretly riding the rooster carousel. I still don’t fully understand why people are so desperate to believe this.

Also, even if we throw out self-reports, I’ll reiterate that Chadopoly believers have to reckon with the fact that STD rates for heterosexual men and women are generally very similar and have been moving in tandem. Sometimes Chadopoly believers will do a google search and discover that more women are diagnosed with Chlamydia, thinking this is a knock-out blow, but this is explained here. Unfortunately, STDs aren’t an ideal proxy for promiscuity more broadly, as factors such as changes in access to testing, testing methods, condom use can confound the signal.

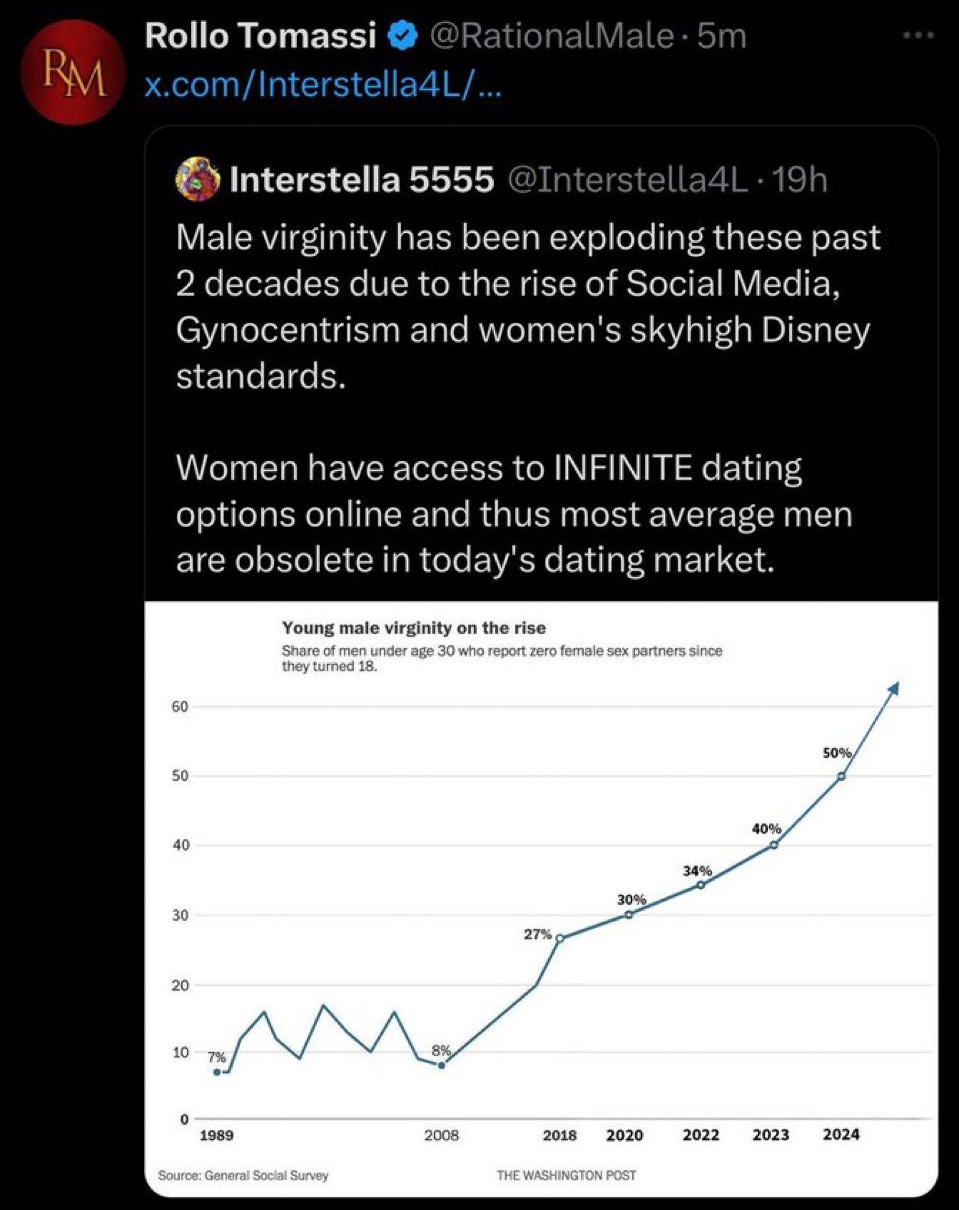

At the end of the day, people will believe what they want. Many have already made up their minds and are clearly engaging in motivated reasoning. I’ve seen Chadspiracists resort to claiming that survey administrators are fudging the numbers to suppress the truth. The ‘godfather of the red pill’ himself will casually repost blatantly fake graphs without hesitation if they serve the grift. The façade of concern such individuals will suddenly show for statistical rigour is a grave insult to our intelligence.

The spike in 2004 is due to a couple of terachads reporting 989 or more partners. Excluding partner counts above 100 shows a similar story.

Note the shrinking gap in reported lifetime opposite-sex partners. This could be due to a fading ‘sexual double standard’, as well as switching to computerised surveys for sensitive questions.

Number of sex partners in the past year and lifetime one-night stands.

Though I’d suggest that this could be mediated by a more extraverted personality, as it’s associated with both variables.

I do wonder though if reverse causality might also be at play; people may rationalise by aligning their views of high-status behaviour with their own sexual practices.

The possibilities for this are that women are having sex with older men, with men who are too rare to be detected in this sample, sample bias, or it’s a false positive.

Another example is reported intercourse frequency, which in a meta-analysis of studies from the 60s to early 90s showed a gender difference of d = .31, while a more recent one showed a difference of g = .04.

Here's my understanding of the "slut overrepresentation" misconception: the squeaky wheel.

Promiscuous women are squeaky wheels. Let's say that promiscuous women are 1% of the population. In my survey, I found that less than 16% of women are on Tinder. However, if all of the promiscuous women are on Tinder, then promiscuous women will *appear* to be 6.25% of all Tinder users.

Next, imagine you're a man swiping right on Tinder. You swipe on 16 different profiles. The first 15 are women without any signs of promiscuity -- no cleavage, no sexual language. However, profile #16 is extremely promiscuous. Because #16 is a squeaky wheel, she stands out more in the man's memory than the 15 other profiles. This biases the man's memory to think that 50% of women are promiscuous.

The other explanation I would put forward is that men tend to ignore ugly women. When men say, "women are promiscuous," they are almost exclusively thinking of and talking about attractive women. Ugly women (femcels) might not be having sex, but as far as men are concerned, these women don't exist.

Attractiveness is difficult to measure in the data, but I would hazard to guess that attractive women have higher body counts than the average woman.

“I still don’t understand why people are so desperate to believe this”

Tbh I think this is a much more interesting phenomenon than the data itself. I can think of tons of contributing factors but idk how you could collect data on it:

1) Women’s promiscuity as a topic in media has been increasing for a while and a lot of guys infer this must be a reflection of reality. Women love songs about having sex all the time, and they’re not having sex with me or anyone I know, so they must be all having sex off screen with the same guy. When in reality, women just enjoy it vicariously through these songs/shows in the same way a guy would enjoy a rapper talking about making a million dollars or killing his opps.

2) Dating apps encourage this thinking because it makes them money. They rly shock even attractive men into a scarcity mindset. Men are constantly seeing women on dating apps but being rejected, so they infer that SOMEONE has to be getting accepted somewhere. Why else would the women be on there? Which leads to the next point

3) Bad mental model of women’s behavior. They just assume women act like they would if they had the same power on dating apps, but don’t understand it’s a completely different game for them. If they were women, they would be having sex constantly until they settled down later in life, so they assume this must be desirable for women too. This also leads to valuing quantity of sex over quality, which most women would find ridiculous.

4) They need Chad to exist because it gives them hope that SOMEONE is being fulfilled by the dating app game. Even if they aren’t, it gives them hope that they’re not wasting all their mental energy being resentful over not getting something that won’t even make them happy. If even the men who get sex from dating apps are unhappy and still face constant rejection, they would need something else to blame for why they feel like shit all the time.