When a guy struggles with women, oftentimes he’ll be advised to ‘work on his social skills’, implying that these are critical to success in the dating realm.

Similarly, the pick-up artist (PUA) industry was built on the premise that a man’s ‘game’—a term describing a set of social skills specifically focused on seduction—was key to picking up women. Its methodical step-by-step approach likely appealed to analytically minded individuals who struggled to intuitively grasp the subtleties of flirting.

Namely, men on the autism spectrum. This condition, primarily marked by impaired communication and social interaction, is commonly linked to dating issues.

Late psychologist Brian Gilmartin coined the term ‘love-shy’ to describe men whose severe anxiety around women led to celibacy. In a 2004 letter, Gilmartin estimated that some 40% of ‘severely love-shy men’ were on the spectrum:

In 1944, Austrian physician and professor Hans Asperger discovered a condition that has come to be known as Asperger's Syndrome. Six out of every seven victims of it are male; and it can be viewed as another name for 'high functioning autism'. Many of us now believe that as many as 40 percent of the cases of severely love-shy men would qualify for a diagnosis of ‘Asperger's Syndrome’.

Autistic men’s attempt at wooing the opposite-sex apparently holds significant entertainment value for neurotypicals, serving as the premise for shows such as Love on the Spectrum and Atypical. In another series, The Undateables, somewhere around half of the male cast was on the spectrum.

The infamous internet lolcow and autistic icon Chris Chan had his own ‘Love Quest’ saga, wherein trolls would pretend to be his girlfriend or even stage a date with him just to humiliate him further.

Autism is also a frequent topic of discussion within the incel sphere, so let’s start there: just how common is it among those who identify as involuntary celibates?

Prevalence among incels

A poll on incels.co with 666 responses found that 40% believed ‘autism or similar conditions’ were a factor that ‘significantly prevented them from finding a partner’.

A study by Moskalenko et al. surveying 274 self-identified incels found an autism diagnosis rate of 18%, rising to 74% when including self-reported autism. Another with a sample of 54 found a diagnosis rate of 32%, rising to 53% with self-reports.

Speckhard & Ellenberg found among 272 incels a diagnosis rate of 18%, with 44% ‘reporting autism symptoms’.

Whittaker et al. administered the AQ-10 (Autism Quotient) questionnaire to 561 self-identified incels, finding that 31% met the threshold for an autism evaluation referral.

A consistent pattern emerges in these results: autism is significantly overrepresented in this community, with around 20% being officially diagnosed, and this figure rising to 50% or higher if we take self-reports seriously. Of course given this overrepresentation even those who fall short of a clinical diagnosis will exhibit significantly higher than average autistic traits.

Another somewhat troubling pattern is the striking overrepresentation—perhaps even ubiquity—of autism among mass killers linked to inceldom.

The most infamous case, Elliot Rodger, was diagnosed with PDD-NOS1 in 2007, which—along with Asperger’s syndrome—now officially falls under the autism umbrella.

From the investigation report:

The suspect would hold his ears when he heard loud noise. He displayed some repetitive behaviors such as making noises, tapping his feet or leg, and perseverating on his responses (such as repeating the words “great” and “cool”). The suspect was believed to display characteristics of high functioning autism or Asperger’s syndrome. … He was very shy in public, had difficulty making friends and cared a lot about what others thought about him. The suspect had anxiety and didn’t like large crowds. In 2007, the suspect made his first purchase without parental assistance when he went to a sandwich shop with a friend and bought a sandwich.

Chris Harper-Mercer, school shooter who complained of being a virgin and having no girlfriend—and who praised Elliot Rodger in his manifesto—was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome.

The next high-profile incel-related terrorist attack was committed by Alek Minassian, who before embarking on a deadly van rampage posted this cringe to Facebook:

Private (Recruit) Minassian Infantry 00010, wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan please. C23249161. The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!

Minassian attended a special ed class for students with autism, and his mother spoke of living with a son with Asperger syndrome. He was described as socially awkward and avoiding eye contact, and would reportedly ‘fidget and twitch, tap his head, hug his arms around his body, meow like a cat, sometimes spit on himself and repeat the phrase, “I’m afraid of girls”’.

His autism came under the spotlight when his lawyers attempted to use it as a defence in court, arguing that it prevented him from understanding the moral implications of his actions.

Then we have Jake Davison, who was diagnosed with autism as a child, and like Minassian was a special ed student.

Unlike the others, he explicitly referenced autism in his complaints:

‘Try being an unemployed, autistic, poor, sexually frustrated male with tons of health issues, no social circle and being stuck in government housing with my mother for years on end, having missed out on so much in life’.

‘Not being able to do the hobbies and things I enjoy as I don't have a car, I am socially isolated and a black sheep who barely interacts with anyone other than a few people at work’.

I’m aware that drawing this connection can be controversial, with many fearing that it risks further stigmatization, but acknowledging these ‘inconvenient facts’ is necessary to achieve a fuller understanding.

It’s often said that autistic people are more likely to be the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence. This may be true, but these incidents should arguably be distinguished from more everyday acts of violence. A cold, calculated killing spree belongs in a different category than impulsive, heat-of-the-moment violence. The former stems from misanthropy and alienation rather than a general predisposition to violence.

Most of these individuals lack a history of violence, after all. Take Elliot Rodger, for instance:

Prior to May 23, 2014, the suspect’s family was unaware of him engaging in any known incidents of violence. In the past, when the suspect became angry, he would tense his entire body while clenching his teeth and pursing his lips. The suspect did not physically act out, get into fights, hurt animals, damage property or otherwise react violently due to his anger. The suspect had no criminal history prior to May 23, 2014.

Of course, autism is not the only factor in this multifaceted issue, but even basic (read: neurotypical) pattern recognition would suggest that it’s at least one ingredient in the cocktail.

There are of course reasons in addition to celibacy which could help to explain these patterns. It’s possible that autistic individuals are more drawn to ‘extreme’ ideologies, and cognitive rigidity could make them more prone to reaching extreme conclusions in general. One of the Moskalenko studies found that autism predicted greater radicalization. Additionally, the incel ideology may appear on its surface as a logical framework for understanding sexual dynamics, which, similar to PUA, could appeal to autistic patterns of thought, and there are mental illnesses and personality traits which are overrepresented among autistic people which might also contribute to these other overrepresentations.

Let’s now see what the research can tell us about the dating and sexual experiences—or perhaps lack thereof—of people on the spectrum.

Is autism the real black pill?

Cederland et al. (2008) studied 70 men with Asperger’s (mean age = 21.5).

Three (4%) were living in a relationship and 10 (14%) had ever had a relationship.

Hofvander et al. (2009) studied 122 high-functioning autists (67% male; median age = 29).

16% had ever lived in a long-term relationship.

Stoddart et al. (2013) gathered data on 480 individuals with autism (72.5% male; mean age = 29.1). 50.8% were higher-functioning, 23.8% ‘had autism’, 15.6% had PDD-NOS, and 14.8% had an intellectual disability.

415 (86.5%) were single, 43 (9%) were married, 11 (2.3%) were separated or divorced, and 10 (2%) were living common-law.

32.1% had been in a romantic or intimate relationship in the past.

10% had biological children.

Barneveld & Swaab (2014) compared the outcomes of 162 high-functioning autistic participants (83.4% male; mean age = 23.7) with subjects diagnosed with other conditions in childhood.

88% of autistic subjects were single, which was significantly more than those in the ADHD, disruptive behaviour, and affective disorders groups.

Helles et al. (2016) studied 50 adults (mean age = 30) diagnosed with Asperger’s as children.

48% had never been in a relationship, 22% were currently single but previously had a partner, 16% were partnered but non-cohabiting, and 14% were married or cohabiting.

There was a negative relationship between relationship status and autism symptom severity (r = –.42).

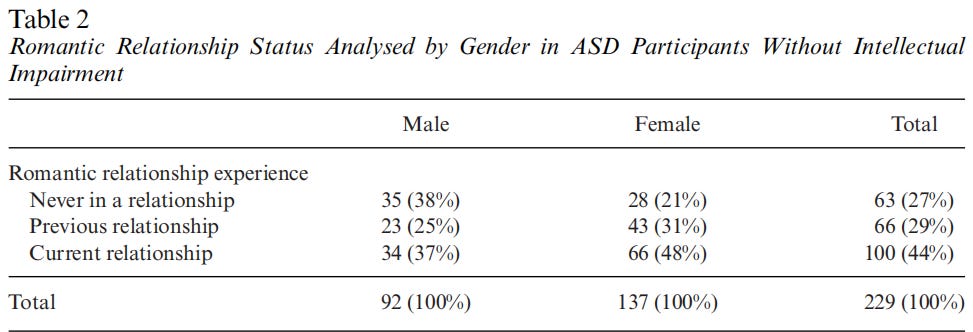

In a study by Strunz et al. (2017), 229 high-functioning autistic participants (40% male; mean age = 35) completed a number of questionnaires relating to relationships.

37% of the men and 48% of the women were currently in a relationship.

A significant gender difference was observed whereby more men (38%) had no relationship experience relative to women (21%).

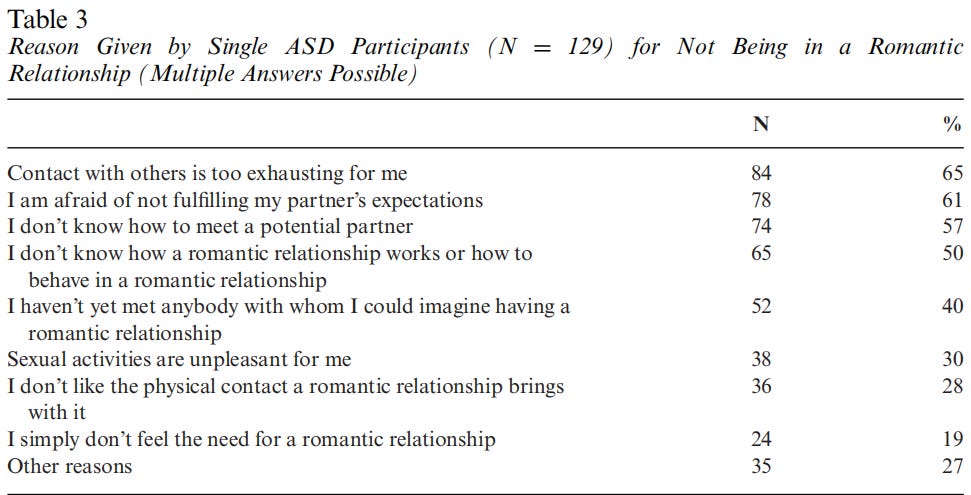

Only 17 (13%) of the participants not currently in a relationship expressed no desire to be in one, with single men expressing a significantly greater desire.

Common reasons given for not being in a relationship included: “Contact with others is too exhausting for me”, “I am afraid of not fulfilling my partner’s expectations”, “I don’t know how to meet a potential partner”, and “I don’t know how a romantic relationship works or how to behave in a romantic relationship”.

Schöttle et al. (2017) compared 96 subjects with high-functioning autism (58.3% male; mean age = 39.2) with 96 neurotypicals (59.4% male; mean age = 37.9).

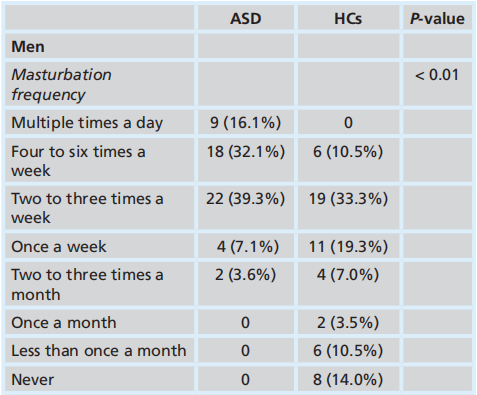

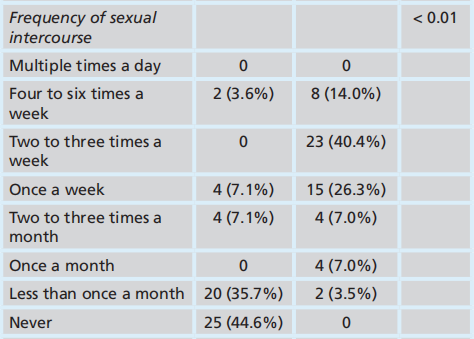

Autistic men masturbated significantly more frequently than NT men: 87.5% of autistic men masturbated at least a few times a week compared to 43.8% of NT men.

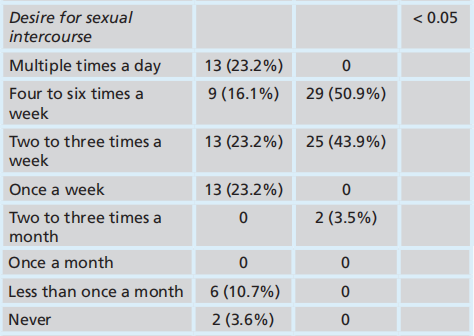

When it came to actual sexual activity, it was another story. While 54.4% of NT men had sex at least a few times a week, 3.6% of autistic men did, and while 35.7% of autistic men had sex less than once a month2 and 44.6% were virgins, only 3.5% of NT men had sex this infrequently and none remained virgins.

This discrepancy in sexual activity came in spite of the fact that autistic men reported high sexual desire. It was also more heterogeneous, with more reporting both higher and lower levels, though only 3.6% reported no sexual desire whatsoever.

For autistic women, 50% were virgins compared to none of the NT women, and 27.5% had sex less than once a month compared to none of the NT women. However, 42.5% of autistic women reported never desiring sex, and 15% desired sex less than once a month, so their sexual activity was much more in line with their desired amount.

Regarding relationships, 16.1% of autistic men and 46.2% of autistic women were in one, compared to 82.4% of NT men and 79.5% NT women. All differences except those between NT men and women were statistically significant.

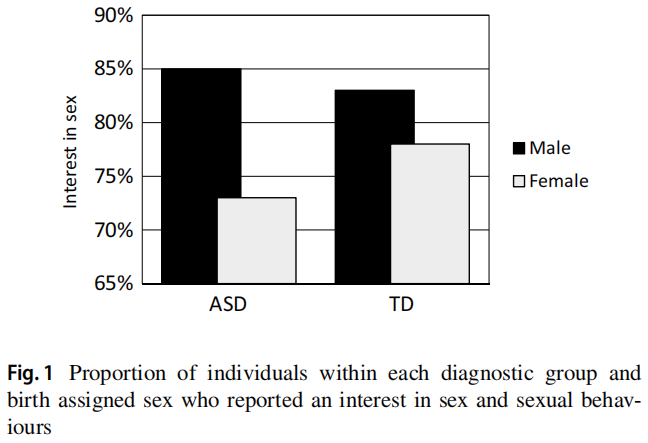

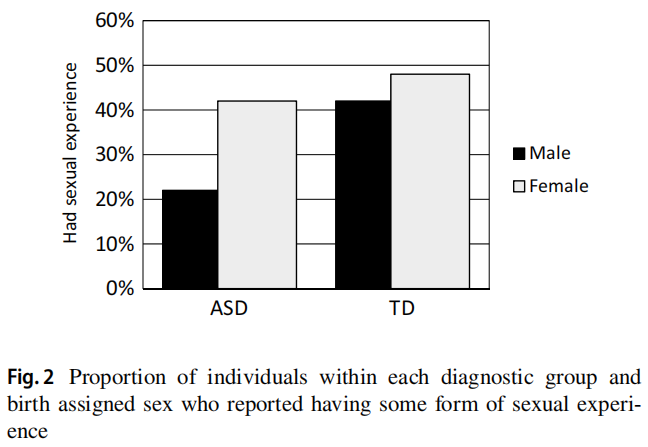

Pecora et al. (2019) studied 232 high-functioning autistic subjects (41.4% male; mean age = 25.1) and 227 NTs (29.1% male; mean age = 22.2).

Significantly more autistic men reported having sexual interest than autistic women, and if anything more than NT men as well.

Despite this, less autistic men reported having sexual experience than all the other groups, who didn't significantly differ from each other. This is also despite the autistic sample being older on average.

Autistic women faced a different issue however, as significantly more of them than their NT counterparts reported experiencing unwanted sexual advances or encounters, implying that their social naivety makes them more vulnerable to being taken advantage of.

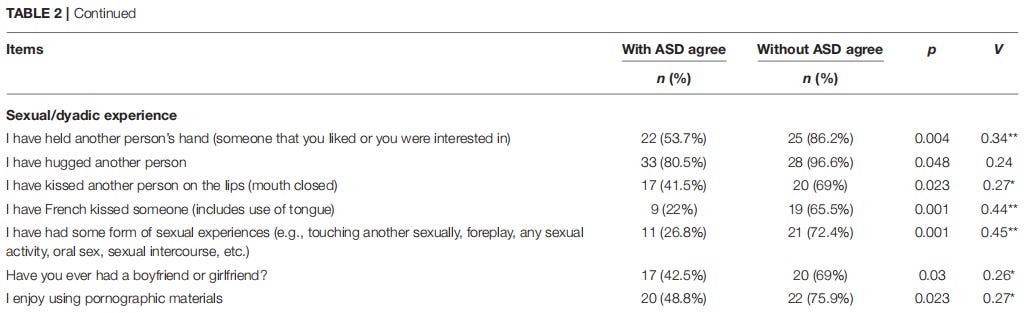

Joyal et al. (2021) studied 68 autistic (41 male, mean age = 19.4; 27 female, mean age = 19.7) and 104 NT subjects (29 male, mean age = 18.4; 75 female, mean age = 19.1).

26.8% of autistic compared to 72.4% of NT males reported having had some form of sexual experience.2

42.5% of autistic males had relationship experience compared to 69% of NT males.

While significant fewer autistic females (59.3%) than NT females (85.3%) had some form of sexual experience, there wasn’t a difference when it came to relationship experience.

Slightly fewer autistic than NT males believed that being in a long-term relationship in the future is important or said they would like to have a boyfriend or girlfriend in the near future, but the differences weren’t quite statistically significant. It is worth mentioning however that a significantly lower percentage of autistic males in this sample said they’d like to have sex with others than NT males.

Weir et al. (2021) analyzed a large sample of 1,183 autistic (36.9% male; mean age = 41) and 1,203 NT subjects (31.4% male; mean age = 41.9), with a wide age range of 16–90.

Among autistic subjects, 70.2% of males and 76% of females stated ever having been sexually active, compared to 88.8% of NT females and 89% of NT males.

5% of autistic males and 13% of autistic females reported being asexual compared to 1.5% of NTs.

In a model adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, education, country of residence, and asexuality, the odds ratios for sexual experience were 0.24 for autistic men and 0.48 for autistic women.

Autistic females had an earlier sexual onset (mean = 18.02) than autistic males (mean = 19.44).

Dewinter et al. (2017) examined a sample of 326 autistic men (mean age = 46) and 343 autistic women (mean age = 40).

50% of autistic men were in a relationship, compared to 74.3% of NT men.

47.2% of autistic women were in a relationship, compared to 70.7% of NT women.

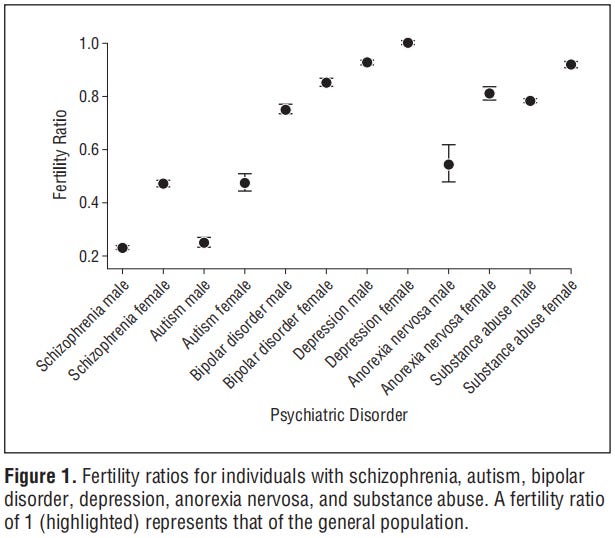

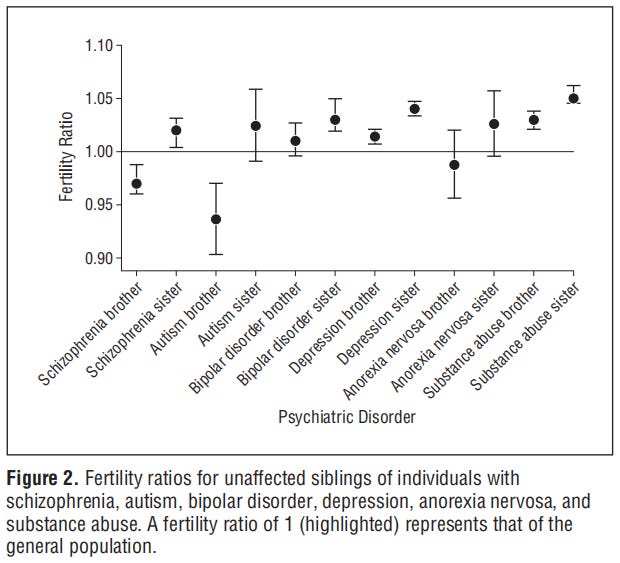

Power et al. (2013) analyzed Swedish population databases containing 2.3 million individuals, comparing the fertility rates of those with various mental disorders to the general population.3 Autistic men had a fertility ratio of 0.25, meaning they had one quarter the number of children as NT men, while autistic women had a ratio of 0.48. Mental disorders in general had a weaker effect on women’s fertility.4

Another intriguing finding was that while unaffected brothers of autistic individuals also had significantly lower fertility ratios, this wasn’t true for any other group barring the brothers of schizophrenics, leaving autism’s persistence over generations a mystery.

Hugh-Jones & Abdellaoui (2022) analyzed polygenic risk scores for various traits using UK biobank data to assess their effects on fertility. Men with higher polygenic risk scores for autism had lower fertility, whereas this wasn’t the case for women. Abdellaoui et al. (2024) further demonstrated a significant association with childlessness.

A study by Ponzi et al. (2016) tested whether autistic traits are linked to restricted sociosexuality and investigated stress and sex hormones as potential mediators. They hypothesized that individuals with high autistic traits may find interactions with strangers they’re attracted to stressful due to poor social skills, which could reduce their motivation or ability to pursue relationships.

In a sample of 107 heterosexual male college students, Autism Quotient scores negatively correlated with past sexual experience (r = -.38), number of lifetime sex partners at (r = -.39), short-term mating orientation (r = -.27), and a lower, nonsignificant long-term mating orientation (r = -.16). The researchers speculate that negative past experiences may discourage short-term mating but don’t necessarily lead to stronger long-term mating preferences.5

While AQ wasn’t linked to peak cortisol after a stress test, it correlated with total cortisol production after controlling for baseline levels, as well as delta cortisol (change from baseline) and AUC-I (area under the curve with respect to the increase) during a sexual arousal test, indicating greater cortisol reactivity and production. AQ also moderated testosterone changes post-task—men with higher autistic traits found the video more stressful, but somewhat paradoxically, they also found it more arousing.

Although the analysis using delta cortisol didn’t yield statistically significant results, cortisol AUC-I mediated the link between AQ and lower short-term mating orientation. Overall, the study found little evidence that physiological sexual arousability plays a significant role in the association between autistic traits and sociosexuality, but suggests that heightened social stress responses may.

Are autistic relationships worse?

In the event that an autistic individual enters a relationship, the challenges of course aren’t guaranteed to end there. Good relationships typically require good communication, but difficulties in emotional expression and comprehension, sensory sensitivities, aversion to touch, and rigid routines may complicate matters. Therefore, it’s worth considering not just whether autistic people can form relationships, but whether they can form and maintain good ones. Here are quick summaries of the relevant studies I came across.

Participants with more autistic traits had relationships which lasted longer.

The severity of autistic traits in married men with high-functioning autism was negatively correlated with their wife’s relationship satisfaction but was not associated with their own relationship satisfaction.

A negative association between AQ and relationship satisfaction was found, but only for men.

Self-reported responsiveness, trust, and intimacy mediated the association.

No partner effect of autistic traits was found, meaning that they didn’t influence the partner’s relationship satisfaction.

Autistic people higher in autistic traits—particularly in the social and communication domains—reported lower dyadic sexual wellbeing, including lower sexual satisfaction, assertiveness, arousability, and desire, as well as higher sexual anxiety and more sexual problems.

High-functioning autistic participants in relationships were significantly less satisfied with their relationships than those in the ADHD, disruptive behaviour, and affective disorders groups.

Participants with more autism symptomology related to social functioning reported lower relationship and sexual satisfaction.

Autistic participants reported a similar level of interest in relationships, but reported fewer opportunities to meet potential new partners, had shorter relationship duration, and greater concern about their future relationships.

Amount of engagement with peers was found to partially mediate these differences in relationship difficulty.

Beffel et al. (2021) found that autistic traits’ association with lower relationship satisfaction might be mediated by higher attachment insecurity.

Aloof personality was associated with lower relationship satisfaction via attachment anxiety and avoidance.

Pragmatic language was associated with lower relationship satisfaction via attachment avoidance.

Rigidity was associated with lower relationship satisfaction via attachment anxiety.

Yew et al. (2023) studied a sample of autistic people and NTs who had autistic partners currently or previously.

Autistic participants reported higher sexual and relationship satisfaction.

NTs reported that their autistic partners were less responsive.

Deguchi & Asakura (2018) interviewed wives of autistic men:

The findings describe a process beginning with wives perceiving their husbands as attractive before marriage and then progressing to feeling discomfort with their husbands and struggling with loneliness after marriage. Experiences with social exclusion/inclusion affected this progression. The wives’ repeated discomfort with their husbands and struggles with loneliness eventually led to a major crisis.

Smith et al. (2021) reported challenges in communication, difficulties reading and interpreting emotions, and idiosyncratic characteristics of the autistic partner, and Yng et al. (2022) found that friends reported difficulties in understanding humor, whereas for life partners it was the failure to keep conversations going and inappropriate terminations.

In the Strunz et al. study, it also found that participants whose partners were also on the spectrum (20% of those in relationships) reported higher relationship satisfaction, and none of the participants who’d separated had been together with an autistic partner, indicating that mutually autistic relationships might be more successful. Khaw & Vernon (2025) found no difference in autistic people’s relationship satisfaction by partner neurotype, however.

What drives these differences?

Dating struggles among autistic individuals are typically attributed to impaired ‘social skills’, a broad term that encompasses both verbal and nonverbal aspects of communication. Autism can influence how an individual perceives others’ communication, how they express their own, and the flow and harmony achieved between the two. Below, we will take a closer look at how certain features associated with autism may contribute to these challenges, beginning with nonverbal communication.

Hans Asperger, not one to sugarcoat, describes his observations on patients:

It will have become obvious that autistic children have a paucity of facial and gestural expression. In ordinary two-way interaction they are unable to act as a proper counterpart to their opposite number, and hence they have no use for facial expression as a contact-creating device. Sometimes they have a tense, worried look. While talking, however, their face is mostly slack and empty, in line with the lost, faraway glance. There is also a paucity of other expressive movements, that is, gestures. Nevertheless, the children themselves may move constantly, but their movements are mostly stereotypic and have no expressive value. … Sometimes the voice is soft and far away, sometimes it sounds refined and nasal, but sometimes it is too shrill and ear-splitting. In yet other cases, the voice drones on in a sing-song and does not even go down at the end of a sentence. Sometimes speech is over-modulated and sounds like exaggerated verse-speaking. However many possibilities there are, they all have one thing in common: the language feels unnatural, often like a caricature, which provokes ridicule in the naive listener. One other thing: autistic language is not directed to the addressee but is often spoken as if into empty space. This is exactly the same as with autistic eye gaze which, instead of homing in on the gaze of the partner, glides by him.

Highlighting these peculiarities, a series of studies have come out in recent years claiming to identify autism with impressive accuracy using machine learning techniques to detect differences in gaze, facial expressions, prosody, gait, social smiling, head movements, and interpersonal synchrony.

I don’t know about claims that assign specific percentages to how much of communication is nonverbal vs. verbal, but the importance of nonverbal communication is hard to deny. Human interactions are dynamic and rely strongly on facial expressions, eye gaze, body movements, hand gestures, and tone of voice to decode emotions and intentions. Across the animal kingdom, courtship displays are central to the mating process, and a similar parallel can arguably be observed in human ‘flirting’.

Much of what makes autistic individuals come across as weird or give others ‘the ick’ stems from unconventional nonverbal behaviour. Before even getting a chance to open their mouth, others may sense that something feels ‘off’, and first impressions can be tough to shake.

First impressions

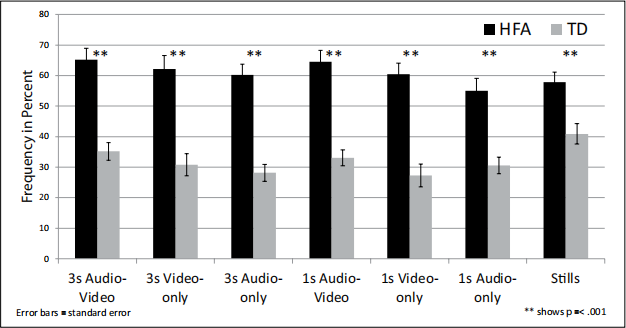

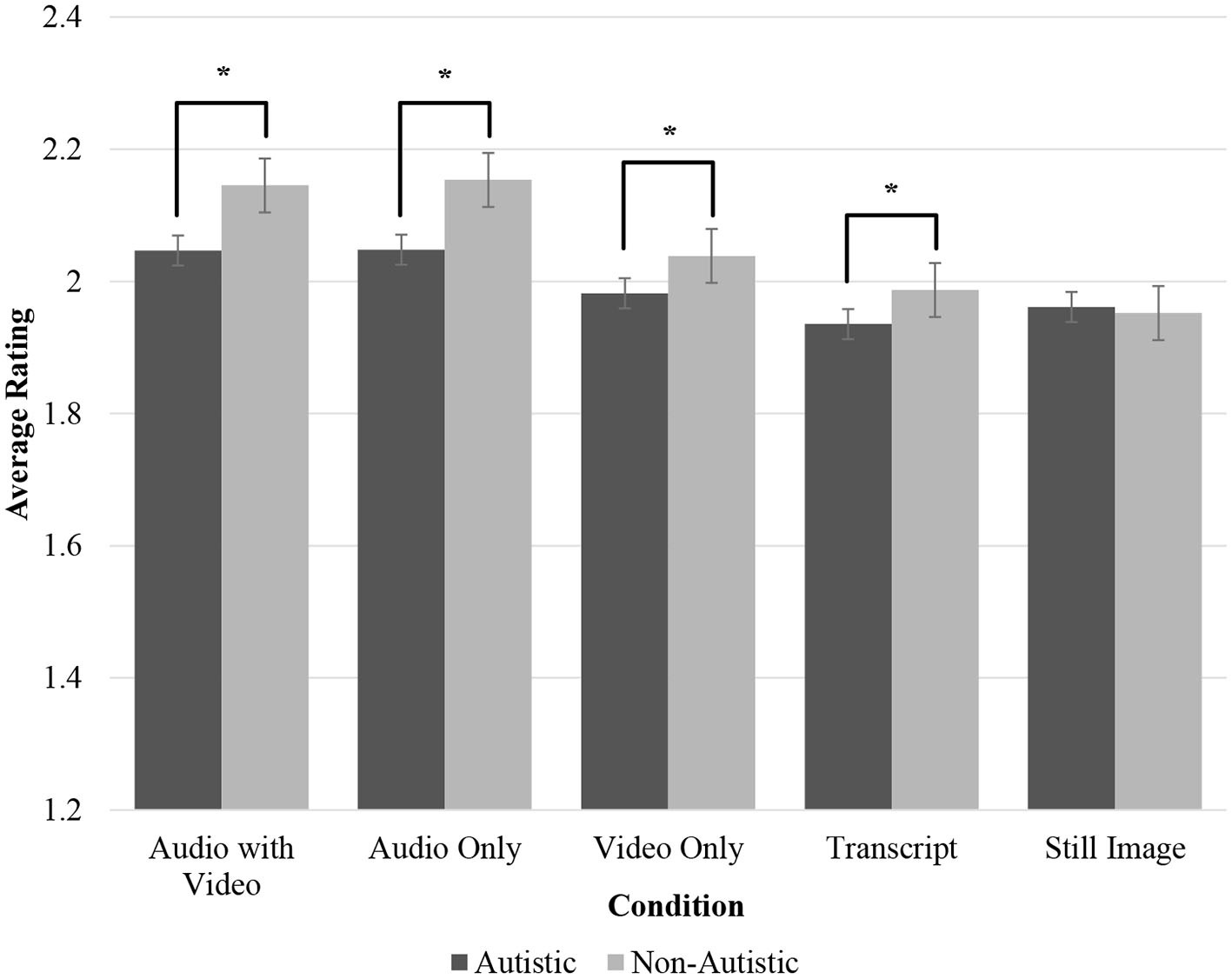

Illustrating this phenomenon, Grossman (2015) found that children with high-functioning autism were rated as significantly more frequently socially awkward than NT children across audio-visual stimuli, video-only stimuli, audio-only stimuli, and still images. Verbal and grammatical content were absent, meaning these impressions must have been based on nonverbal aspects of communication.

The finding that autistic children were rated as more awkward even in the still image condition surprised the researchers. A possible ‘black pill’ explanation exists for this, but they note how facial dysmorphology is more characteristic of the lower IQ subgroup with more severe symptomatology. A more plausible explanation lies in the fact that these stills were extracted from videos, and autistic children often moved towards the edges of the video frame by slouching, leaning, or rocking, whereas NT children tended to remain centred, and autistic children were more likely to move their limbs into the frame. Also, the fact that audio-only content was rated as more awkward would seem to contradict a morphological interpretation. I’ll add that a previous study by Grossman et al. (2013) looked at freeze-frames vs. video codes and only found group differences in perceived facial awkwardness in the latter.

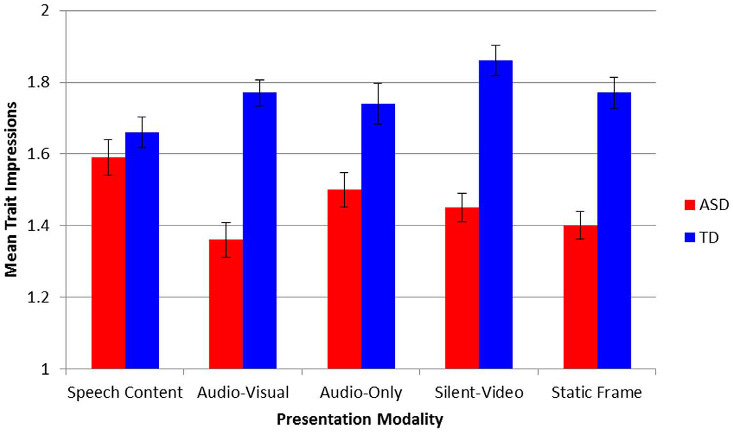

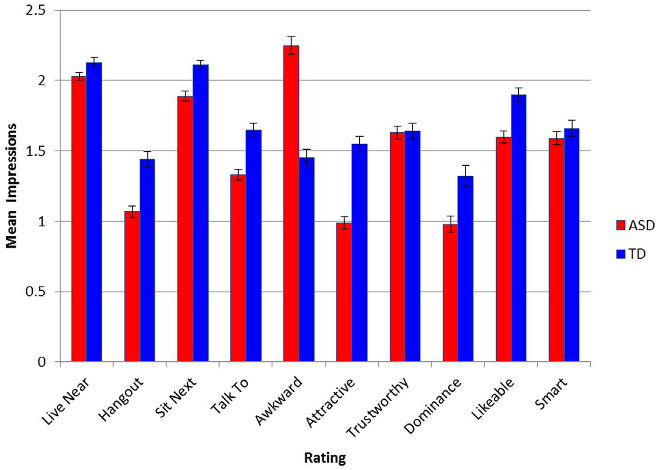

Sasson et al. (2017) replicated these findings for both children and adults using both brief and somewhat longer 10 second clips, and found no effect of repeated exposure.

They also observed that these negative impressions were associated with less interest in engaging with autistic people socially.

While impressions of autistic targets remained unchanged with additional information beyond a static image, NT targets saw improvements with additional visual information, suggesting that body language typically improves perceptions, but not for autistic individuals.

We also see no effect of autism on trustworthiness or intelligence ratings, suggesting that the negative impressions relate more to social desirability than character or competence. That said, some studies (Alkhaldi et al., 2019; Foster et al., 2024) do seem to show differences in these traits, but generally smaller than in other categories.

Alkhaldi et al. (2021) found that perceivers liked NT targets over autistic ones, and cited awkwardness and lack of empathy as reasons for disliking targets.

Stagg & Thompson-Robertson (2023) found that children rated their autistic peers lower than NT peers across silent videos, speech, or—in contrast to previous findings—transcriptions, and the content of the speech was judged as negatively as the delivery style.

Boucher et al. (2023) found that autistic children were rated more negatively than NT children, particularly in conditions involving audio. Raters higher in social competence and ‘explicit autism stigma’ gave more negative ratings to autistic children, while raters with more autistic traits and positive past experiences with autistic people rated them more positively. This study also found that the content of the speech mattered. The still image condition showed no difference in ratings by autism condition.

They posit that the difference between this and Sasson et al. may be due to how the images were generated. In this study, the frames taken for the images were the first ones in the video, where the child’s eyes were open and heads upright, so atypical social behaviour such as looking down or away during the conversation may have been avoided.

Morrison et al. (2019) extended these findings to real-world social interactions lasting five minutes. Autistic adults were rated as more awkward, less attractive, and less socially warm by both NT and autistic interaction partners, but only NT adults expressed greater social interest in NT partners. Autistic participants, if anything, preferred other autists and reported disclosing more personal information to them, which the authors interpret as providing support for the ‘Double Empathy Problem’.6 Similarly, Crompton et al. (2020) found that NT pairs reported higher rapport than mixed and autistic pairs, but autistic pairs also reported higher rapport than mixed pairs. This was also supported by ratings by autistic and NT observers: mixed pairs were rated lower on rapport, while autistic pairs were actually rated higher than NT pairs.

Norris et al. (2024) found that autistic job candidates were perceived as having a more monotonous tone of voice, being less composed and focused, displaying less natural eye contact and gestures than NT candidates, and received lower ratings for likelihood of social approach. NT candidates received higher ratings in confidence and communication skills when assessed by video compared to transcript, but this wasn’t the case for autistic candidates. This study also adds to the previous ones finding that transcripts of autistic candidates were in fact perceived as worse.

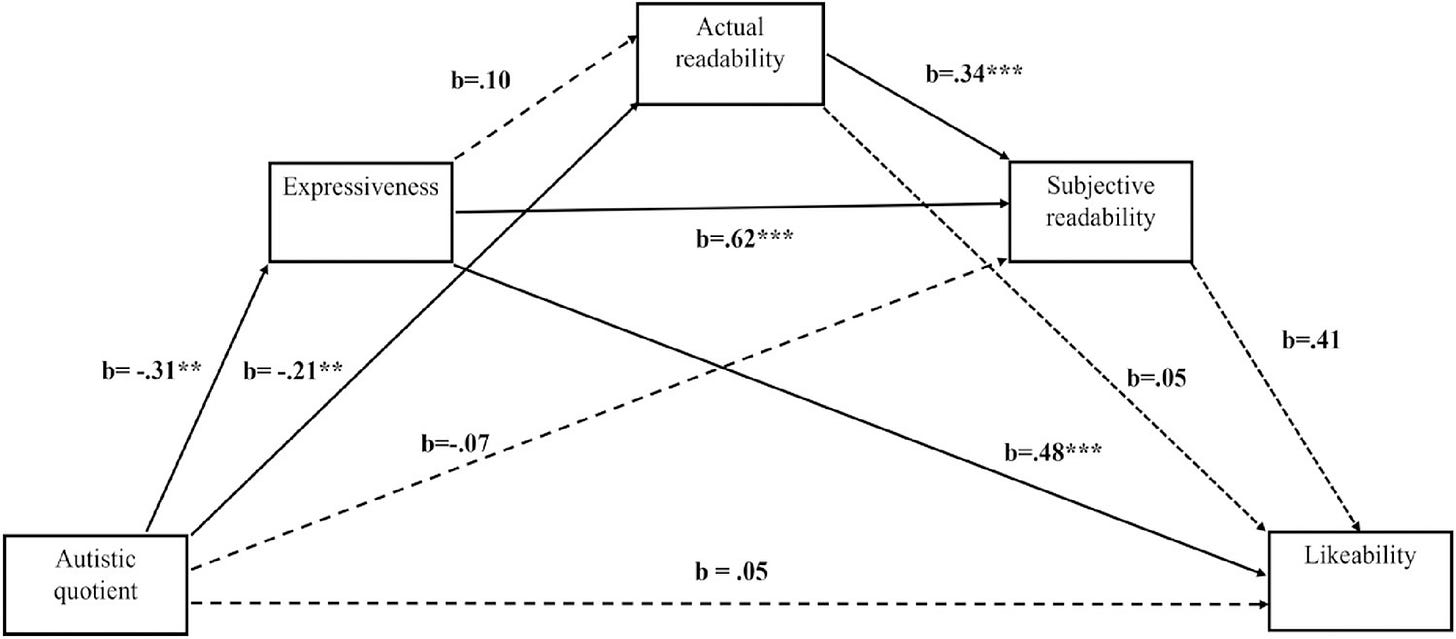

One candidate explanation for these worse impressions is the readability of autistic individuals. Alkhaldi et al. (2019) found that videos of autistic targets from a previous study were rated as less socially favourable than those of NT targets, and target readability correlated with these ratings at r = .58 and r = .64 for each group. Perceivers’ ratings were influenced by the situations targets experienced, suggesting that impressions aren’t formed based simply on appearance, but also on contextual social cues.

A possible reason for this finding is that interacting with people we feel we understand well is more rewarding, leading to greater attraction. This is supported by Anders et al. (2016), who found that attraction to targets correlated with self-reported confidence in identifying their emotional state. They also showed how activation in core areas of the brain’s reward system predicted shifts in attraction. Another possibility is reverse causality—negative perceptions may lower the motivation to empathize.

Another candidate is expressiveness. Alkhaldi et al. (2024) filmed 60 participants experiencing four scenarios and found that Autism Quotient scores negatively correlated with perceiver ratings of readability, social favourability, likeability, and expressiveness, as well as objectively measured readability. While AQ directly reduced objectively measured readability, which in turn correlated with social favourability and likeability, expressiveness fully mediated these effects.

Fultz et al. (2023) reviewed 10 studies on expressivity (both self- and observer-rated) and liking, finding effect sizes comparable to those reported for physical attractiveness. While they didn’t mention this explicitly, the effect observed in these studies holds after controlling for physical attractiveness.

In the next sections, we’ll explore in more detail what it is about how autistic people express themselves that sets them apart and shapes these impressions.

Facial expressivity

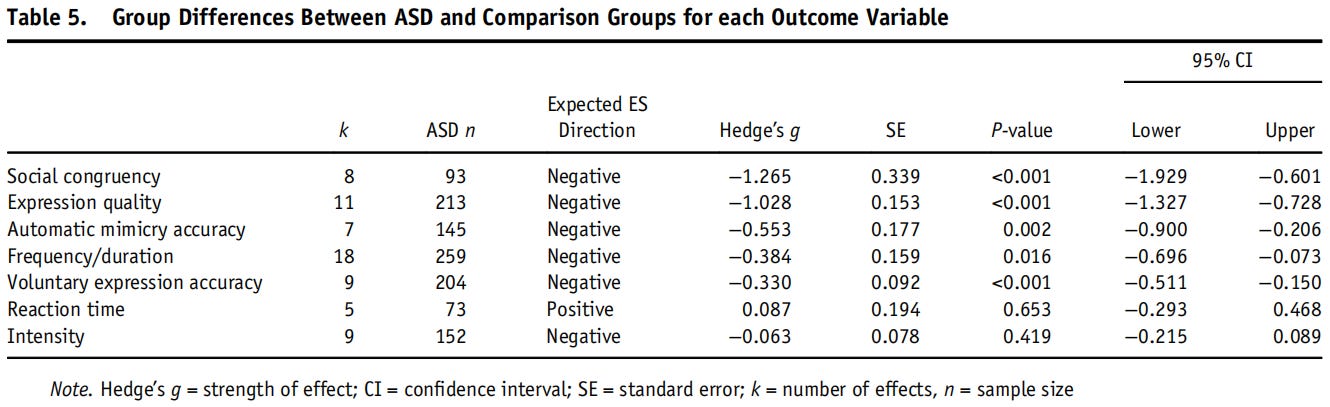

In a meta-analysis of facial expression production in autism, Trevisan et al. (2018) reported a moderate effect size of −0.48 for differences in facial expressions. More specifically, it was found that autistic subjects displayed facial expressions less frequently and for less time, are expressed less accurately, were less likely to share expressions with others or automatically mimic expressions, and their expressions were judged as lower in quality, however, they didn’t express emotions less ‘intensely’, nor did they take longer to react expressively to stimuli. It was also found that autistic individuals naturally produce expressions differently, but are less impaired when it comes to expressing them when explicitly prompted to.

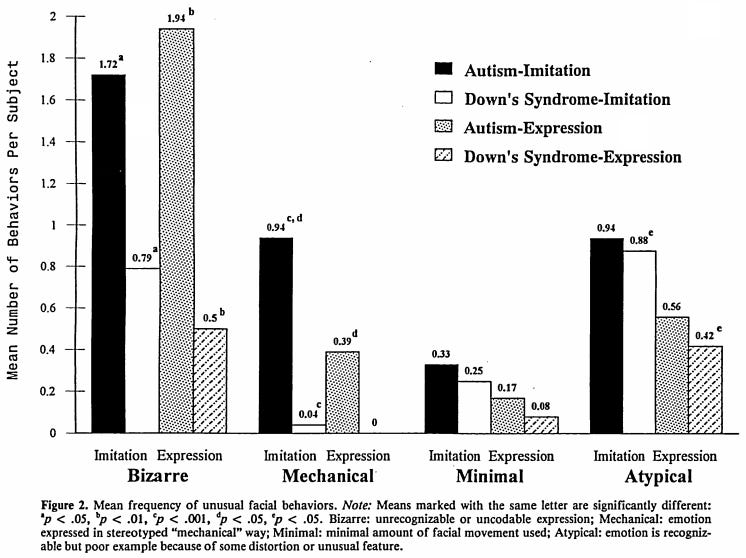

While autistic expressions may not be less animated, they are more ‘odd’. For example, Yirmiya et al. (1989) found that autistic children produced ‘unique’ and ‘unusual’ facial expressions, including blends of incompatible emotions which weren’t observed in normally developing or mentally retarded children. Likewise, Loveland et al. (1994) found that autistic subjects responded to tasks in more ‘bizarre’ or ‘mechanical’ ways than did Down’s syndrome subjects.

Grossard et al. (2020) used computer vision methods, which also determined that production of facial expressions in autistic children carried more ambiguity.

To get a better idea of how autistic individuals spontaneously express emotions in social situations, I have done a brief review of the literature. Below are the relevant key findings.

Snow et al. (1987) videotaped 15 minute interactions involving 10 autistic and 10 developmentally delayed children with their mothers, a psychiatrist, and a nursery teacher, and had a coder record their affective expressions using a behaviour checklist.

Autistic children displayed less positive affect than developmentally delayed children.

The positive affect displayed by autistic children was more likely to be related to solitary activities than social partners.

No difference was found in the frequency of negative affect displays.

Dawson et al. (1990) videotaped interactions involving 16 autistic and 16 normally developing children with their mothers in three situations: a free-play period, a more structured period during which communicative demand was made on the child, and a face-to-face interaction.

Autistic and NT children didn’t significantly differ in the frequency or duration of smiles displayed, and neither displayed frowns.

Autistic children were less likely to combine smiles with eye contact to convey communicative intent.

Autistic and normal children were not found to differ in the percentages of smiles they displayed to social versus nonsocial events.

Autistic children smiled less in response to their mother’s smiles.

Mothers of autistic children smiled less and were less responsive to their children’s smiles.

Kasari et al. (1990) examined the attentional and affective expressions of 18 autistic, 18 normally developing, and 18 mentally retarded children during nonverbal communication acts. Autistic children displayed less positive affect than normal and mentally retarded children during joint attention situations, sharing positive affect with the adult less than one-quarter of the time compared to about three-fifths of the time for the other groups.

Reddy et al. (2002) compared a group of 19 autistic and 16 Down’s syndrome children matched on nonverbal mental age.

For autistic children, laughter was rare in response to funny faces or socially inappropriate acts, but was common in strange or inexplicable situations.

In interaction situations, autistic children rarely attempted to join in with others’ laughter, rarely attempted to re-elicit it through acts of clowning or teasing, and showed lower frequencies of attention or smiles in response to others’ laughter, but showed higher frequencies of unshared laughter.

Wetherby et al. (2004) had two raters view videotapes of 18 autistic, 18 mentally retarded, and 18 normally developing toddlers and code the SORF (Systematic Observation of Red Flags).

83% of autistic toddlers showed some lack of warm, joyful expressions with gaze, compared to 33% of mentally retarded and 6% of normal toddlers.

94% of autistic toddlers showed some lack of sharing enjoyment or interest, compared to 56% of mentally retarded and 6% of normal toddlers.

100% of autistic toddlers showed some lack of coordination of gaze, facial expression, gesture, and sound, compared to 61% of mentally retarded and 17% of normal toddlers.

17% of autistic toddlers showed some flat affect or unresponsive to interactions, compared to 6% of mentally retarded and 0% of normal toddlers.

Nichols et al. (2014) studied 42 younger siblings of children with autism, 15 of who were found to demonstrate autism symptomatology at time 2, and 25 siblings of NT children. At 15 months, social smiling was examined. Social smiling was coded when the child laughed or smiled within 1/10 of a second before or after a look to the examiner's face.

Both autistic sibling groups displayed lower levels of social smiling than the siblings of NTs.

Only the autistic siblings with autistic symptomatology displayed less eye contact and non-social smiling than the siblings of NTs.

Filliter et al. (2015) studied 66 children, 44 of which were younger siblings of autistic children, and 22 of these having received a diagnosis at age 3 while the other 22 didn’t. They were videotaped during the administration of the 'Autism Observation Scale for Infants', during which the frequency and duration of smiles were coded.

At 12 months, infant siblings with autism had a lower rate of smiling than the other groups.

At 18 months, infant siblings with autism continued to display a lower rate of smiling than infant siblings without autism, but not comparison infants.

Dow et al. (2017) videotaped interactions of 130 autistic, 61 mentally retarded, and 56 normally developing toddlers and had research assistants review them and use the Systematic Observation of Red Flags (SORF) to rate the presence of autism related behaviour. The most relevant items show substantial differences between all groups:

Autistic toddlers displayed fewer warm, joyful expressions7 than mentally retarded (d = 0.5) or normal (d = 0.8) toddlers.

Autistic toddlers displayed reduced facial expressions8 than mentally retarded (d = 0.4) or normal (d = 0.9) toddlers.

Autistic toddlers displayed reduced coordination of nonverbal communication9 than mentally retarded (d = 0.9) or normal (d = 1.6) toddlers.

Dow et al. (2020) applied the SORF to a sample of 84 autistic, 82 mentally retarded, and 62 normally developing toddlers who were videotaped at home interacting with their parents, and found similar but somewhat smaller differences.

Macari et al. (2018) had 43 autistic, 16 mentally retarded, and 40 normally developing toddlers complete tasks designed to elicit emotion.

Autistic toddlers exhibited less intense fear than mentally retarded and normal toddlers, more anger than mentally retarded toddlers (but the difference between them and normal toddlers wasn’t significant), and no differences in joy intensity were detected.

Autistic symptom severity wasn’t associated with fear or anger intensity, but predicted lower joy intensity.

Lai et al. (2020) conducted interviews of 23 high-functioning autistic, 14 Williams syndrome, and 26 normally developing children, and coded their facial expressions using a facial movement system. Autistic children produced significantly less facial expressions than Williams syndrome and NT children, but especially smiles, in which they produced less than a third the amount.

Alvari et al. (2021) employed AI software designed to analyze facial micromovements in home videos of 18 autistic and 15 NT infants during their first ecological interactions between 6 and 12 months of age.

Reduced frequency and activation intensity of social smiles was computed for children with autism.

Machine learning models enabled facial behaviour to be mapped consistently, revealing early differences hard to detect by the untrained eye.

Day et al. (2022) recorded 17 autistic and 20 normally developing toddlers complete a series of tasks designed to elicit emotion and had two research assistants code their behaviour.

Autistic toddlers displayed less positive affect in face, voice, and body, through the difference wasn’t statistically significant for voice.

Autistic toddlers displayed greater frustration overall.

Groups were similar when it came to fear inducing tasks.

Jacques et al. (2022) recorded play sessions of 37 autistic and 39 normally developing children and had two raters assess the videos.

No differences in positive, negative, or neutral emotional expression were found.

Differences in unknown emotions were found however, which were unique to the autistic group.

Repetitive behaviours co-occurred with positive, neutral, and unknown emotions but not with negative emotions for autistic children.

Foster et al. (2024) recorded 21 autistic and 21 NT adults in an ‘ideal job interview’ and discussing a personal interest, measuring the percentage of time displaying positive, neutral, and negative affect using facial movement detection software. 335 NT undergrads rated them using the first impression scale.

NTs were rated as displaying more positive affect than autistic participants.

Autistic participants received less favourable first impressions.

Negative affect among autistic participants was moderately to strongly related to worse impressions in job interviews, a pattern which wasn’t found to the same degree among NTs.

Impressions showed more of an improvement in the interest condition for autistic than NT participants.

Northrup et al. (2024a) examined emotional expression in 17 autistic and 20 NT toddlers during emotion elicitation tasks aimed at eliciting joy, frustration, and unease. Video recorded tasks were coded in ten second intervals for emotional valence and intensity.

Autistic toddlers spent more time in neutral facial expressions, and less time displaying positive affect.

Autistic toddlers had slightly less intense positive emotional expression.

Autistic toddlers had slightly more intense negative emotional expression, but there weren’t significant differences in duration.

Zampella et al. (2024) used computer vision to quantify smiling in 60 autistic and 67 NT youth during conversations.

Autistic youth smiled less and their smiles were less prototypical than NT youth.

The association between smile activity and interaction quality approached statistical significance for autistic youth.

In a study by Tetreault et al. (2025), 18 autistic and 17 NT young adults participated in a social stress task. Across four observational episodes alternating between engagement and disengagement of social conversational partner, valence and intensity of facial affect were coded. Autistic participants displayed attenuated affective expressivity overall, driven mainly by a smaller proportion of positive and a greater proportion of neutral affect displays.

Overall, these findings align with Asperger’s observation that ‘It will have become obvious that autistic children have a paucity of facial and gestural expression’. Autistic children tend to display more neutral facial expressions, primarily due to reduced positive expressivity, while negative expressivity shows little difference—though it may be slightly more prevalent. This seems to be especially evident in social settings, where autistic individuals share less positive affect, possibly reflecting a lower reward value for social interaction.10 There is also evidence that when positive emotions are expressed spontaneously, such as smiling, they appear more subdued. These expressions are also, again, weirder on average.

Since these differences emerge early in development—much like reduced eye contact—they’re likely part of the package rather than simply being a consequence of receiving less positive social reinforcement. A bidirectional effect is also possible, however, with a reduced display of positive emotion negatively influencing others’ perceptions, leading to fewer reciprocal social exchanges that would otherwise encourage more positive expressivity.

While the majority of research on facial perception has focused on physical morphology, a good deal of research also shows that facial expressions of positive emotion foster more favourable impressions:

Reis et al. (1991) photographed 30 undergrads, once with a neutral expression and once while smiling, and had photos rated separately. Smiling increased rated attractiveness with a medium effect size and was also associated with perceived sincerity, sociability, and competence, independently of attractiveness.

Berry & Hansen (1996) videotaped six-minute conversations between unacquainted dyads and had both participants and independent observers evaluate the quality of interactions. Participants also filled out the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, revealing that positive affect was positively related to both participant and observer evaluations. In another study, undergrads kept diaries of their interactions for a week, once again finding that positive affect predicted better interaction quality.

Bono & Ilies (2006) found that in naturalistic workplace settings, leaders’ positive emotional expressions were associated with higher charisma ratings. These expressions also influenced followers’ moods, which in turn shaped perceptions of leader effectiveness. Notably, these effects were independent of physical attractiveness.

Golle et al. (2013) found that looking happier could compensate for unattractiveness, with faces manipulated to be less attractive but smiling even being preferred over more attractive but less happy faces. The reverse was also true—facial attractiveness influenced expression judgments, with happiness being detected more easily in attractive faces.

Hepp et al. (2019) found that positive affect display mediated the association between borderline personality disorder and negative evaluations at zero acquaintance. Similarly, both positive and negative affect display mediated the association with trustworthiness. Presumably, similar mediation effects would exist for autism.

There is evidence of a shared neural basis for facial affect and attractiveness processing. O’Doherty et al. (2003) had participants view neutral or mildly happy expressions and found that among comparably attractive faces, smiles enhanced activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex—the same brain region which is activated when viewing attractive faces and which is associated with reward processing.

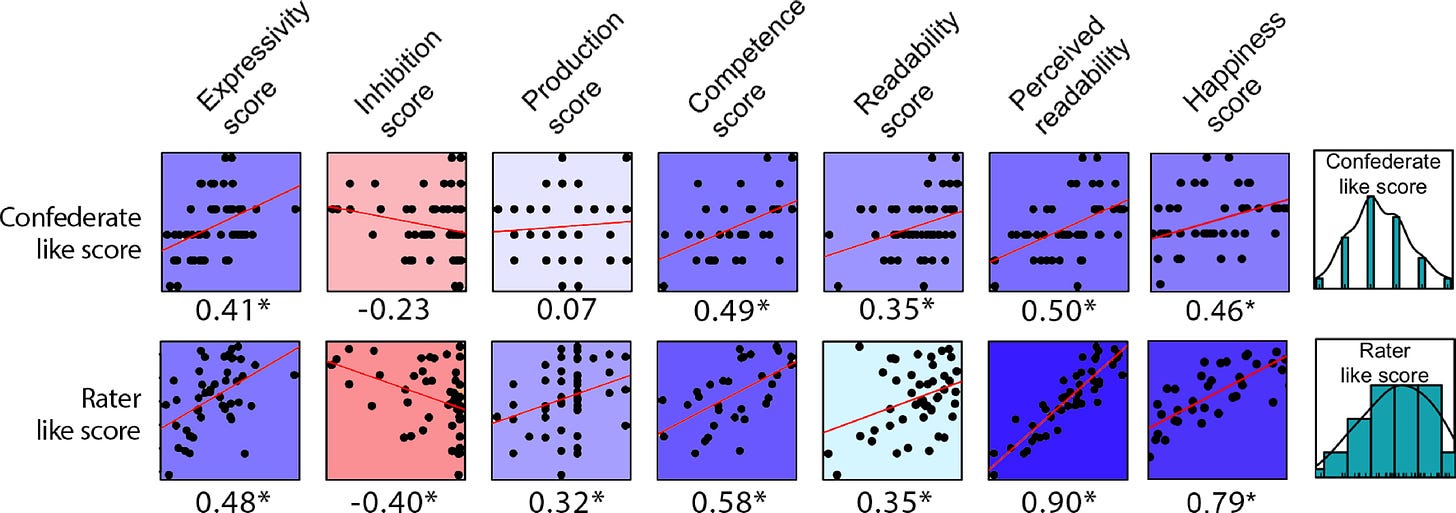

Kavanagh et al. (2024) examined the role of facial expressivity in social interactions. In the first study, participants engaged in semi-structured video calls with confederates posing as participants, as well as social tasks such as ‘disagreeing without being disliked’. These interactions were rated by 176 independent observers. A second study extended this by analyzing 1,315 unstructured video calls.

The authors argue that facial expressivity is a stable trait that varies in the population. In support of this, they showed that facial expressivity correlated quite strongly across different contexts, social partners, and over time.

This study is particularly compelling, as rather than relying on subjective ratings, facial movement was coded using automated detection software, and then a number of measures were used to produce scores for the following:

Expressivity: overall facial expressiveness.

Inhibition and production: the ability to inhibit or produce facial movements appropriately.

Readability: the alignment between participants’ self-reported motivations and raters' judgments.

Competence: the ability to communicate a message effectively through facial expressions.

Replicating the relationships documented so far, both interaction partners and outside observers preferred faces that were more expressive, happier, and more readable—both objectively and subjectively. Effects were also found for competence, and—at least for independent observers—production and inhibition scores. Expressivity was also related to agreeableness, and to negotiation success—but only for those who were more agreeable.

In a large dataset of unstructured conversation recordings, expressivity was again found to increase liking. In this dataset, extraversion had the strongest effect on expressivity, while agreeableness and neuroticism also showed effects. Extraversion and smiling also positively influenced liking.

Together, these results suggest that facial expressivity serves an important affiliative function, and its atypical manifestation in autism may help explain interpersonal difficulties.

Eye contact

Reduced eye contact is a hallmark of autism, emerging early in development.

Bottein & Hamilton (2024) reviewed studies on adolescents and adults with autism and found that while broad gaze patterns were similar between autistic and NT participants, gaze to the eyes was reduced in individuals with autism or those higher in autistic traits. Autistic participants appear to modulate their gaze similarly to NTs however, spending less time looking at the face while speaking than while listening.

Stuart et al. (2023) reviewed studies on eye gaze and activity in the ‘social brain’ during facial stimulus processing, concluding that the evidence leans in favour of the ‘eye avoidance hypothesis’ and suggesting that gaze aversion serves to reduce hyperarousal in the amygdala so as not to trigger a fight-or-flight response.

Gaze is a powerful social signal that, as mentioned, can trigger physiological arousal. It can also enhance perceptions of charisma, signal engagement, and build rapport and trust. Conversely, an averted gaze may signal disengagement or coldness, making it one more factor working against autistic individuals. Eye contact is commonly used to signal liking and attraction, and it may also help generate it:

Mason et al. (2005) found that female faces were rated as more likeable and attractive when their gaze shifts signaled engagement rather than disengagement. This effect was also context-sensitive, influencing only men's perceptions of attractiveness.

Conway et al. (2008) found that participants preferred direct gaze when judging the attractiveness of happy faces compared to disgusted faces, an effect that was pronounced for opposite-sex faces. Replicating the prior study, this opposite-sex bias was absent for judgements of likeability.

Ewing et al. (2010) found that men were more likely to choose a woman’s face with direct gaze over the same face with an averted gaze. This preference was stronger for more attractive faces, but still persisted for less attractive faces.

Kaisler & Leder (2016) examined gaze effects in natural scenes featuring two faces. When a face made direct eye contact with the perceiver, it was rated as more attractive and trustworthy. When direct gaze was omitted, faces that were being looked at by another person were still perceived as more trustworthy.

Hoffman et al. (2024) conducted a speed-dating experiment, revealing that sharing and receiving (but not giving) eye contact tripled the likelihood of a positive mate choice during a 5-minute date. Notably, this effect was unrelated to perceived attractiveness, which had a weak but significant correlation with mutual face contact (r = 0.16, p = 0.02), but not mutual eye-contact (r = 0.1, p > 0.05).

Prosody

Another area in which expressive abnormalities have been documented is vocal prosody—variations in pitch, tempo, rhythm, and intonation that convey emotion and meaning in speech.

A meta-analysis by Asghari et al. (2021) found that autistic individuals displayed significantly higher pitch (SMD = −0.4, 95% CI [−0.70, −0.10]), wider pitch ranges (SMD = −0.78, 95% CI [−1.34, −0.21]), longer voice durations (SMD = −0.43, 95% CI [−0.72, −0.15]), and greater pitch variability (SMD = −0.46, 95% CI [−0.84, −0.08]). No significant differences were found in pitch standard deviation, voice intensity, or speech rate.

Wehlre et al. (2022) analyzed around 20 minutes of semi-spontaneous speech from 28 dyads consisting of 14 autistic and 14 NT adults matched for age, sex, and verbal IQ. They argued that the most common method used to measure intonation styles is insufficient for determining whether speech is more ‘singsongy’ or ‘robotic’, and opted to use their own method incorporating the dimensions of 'spaciousness' (measuring the excursion of pitch contours) and 'wiggliness' (measuring the time-varying dynamics of pitch contours). Their findings showed that autistic speech was both more spacious and wiggly, supporting prior studies suggesting autistic individuals tend to have a more ‘singsongy’ intonation style.

These findings seem to challenge the stereotype that autistic people tend to speak in a monotone.

As with facial expression, however, autistic prosody is judged as more unusual and less natural by perceivers.

Grossman & Tager-Flusberg (2012) found that while autistic individuals were able to produce accurate facial and vocal emotional expressions, as well as lexical stress, their prosody was still perceived as qualitatively more awkward. Likewise, Hubbard et al. (2017) found that although listeners were actually more accurate at identifying emotional context from autistic speech, it was nonetheless rated as sounding less natural. In contrast, Gargan & Andrianopoulos (2021) found that autistic individuals were less accurate on prosody tasks, but replicated the finding of autistic individuals being judged as sounding unnatural.

Nadig & Shaw (2012) further observed that while autistic speakers were rated as having atypical prosody, they weren’t rated as having increased pitch variation—despite this being objectively the case. This might not have been properly registered because of the unconventional quality of the pitch variation.

Other studies have indicated that autistic people have difficulties with prosodic stress—the way certain syllables or words are emphasized in a sentence, as well as phrasing—the way words and phrases are arranged (Shriberg et al., 2001; Paul et al., 2005; Patel et al., 2023).

A meta-analysis by Loveall et al., (2020) found that high-functioning autistic individuals have weaknesses in imitating and discriminating prosodic form and using prosody to express and understand emotional affect.

Finally, Asgari et al. (2021) showed a wider range of loudness for autistic subjects, in line with the idea that some autistic people speak ‘too quietly’ and some ‘too loudly’.

Movement

Yet another commonly observed area of abnormality in autistic individuals involves both fine and gross motor movements, affecting everything from handwriting to the movement of the body through space.

A meta-analysis by Coll et al. (2020) analyzing sensorimotor differences between autistic and NT individuals found an overall effect size of Hedges’ g = 1.22 (SE = 0.08; CI = 1.08–1.37; p < 0.001), indicating that autism is associated with large deficits across motor skills, motor coordination, motor control, postural stability, and visuomotor integration.

Wang et al. (2022) found that in addition to autism being associated with a large deficit in gross motor skills (Hedges’ g = −1.04), there was also a modest correlation between these deficits and social skills deficits (r = 0.27).

A meta-analysis by Lum et al. (2021) on gait anomalies in autism found that autistic individuals exhibited a wider step width, slower walking speed, longer gait cycle, longer stance time, and longer step time. Additionally, autism was associated with greater intra-individual variability in stride length, stride time and walking speed.

Gong et al. (2020) found that autistic children walked with more flat-footed contact pattern, more left–right asymmetry, and larger step-to-step variability than NTs. These gait abnormalities were associated with social impairments measured by the AQ and the Social Responsive Scale.

Cook et al. (2013) recorded the horizontal sinusoidal arm movements of autistic and NT participants and found that autism was associated with atypical kinematics, characterized by greater acceleration, velocity, and jerkiness. These atypical movement patterns correlated with autism symptom severity, as well as a bias towards perceiving biological motion as ‘unnatural’.

Edey et al. (2016) found in addition to autistic participants moving with increased jerk, NTs were better able to identify the mental state portrayed in the animations produced by NT individuals.

Aransih & Edison (2019) had 30 NT participants rate the naturalness of 2D side-to-side arm movements recorded from NT and autistic individuals. Autistic movements were perceived as being significantly less natural, and these perceptions were influenced by jerk, acceleration, and velocity.

Lewis et al. (2024) found that the level of autistic traits in neurotypical individuals also predicted kinematic idiosyncrasies, being associated with the order, volume, and magnitude of their emotional movement patterns (their performances of reactions to prompts such as ‘After returning from a weekend getaway, you find that your roommate has trashed your apartment and completely ignored your agreements, which makes you very angry’).

These quirks further contribute to the ‘weirdness factor’ which leads to less favourable impressions of autistic individuals. After all, person’s gait is often the first nonverbal cue others are exposed to when meeting them. Motoric abnormalities can disrupt the fluidity of social exchanges, which rely on subtle, synchronized coordination.

Interpersonal synchrony

This dynamic social coordination, dubbed ‘interpersonal synchrony’, involves the unconscious mirroring of gestures, expressions, posture, and speech patterns between interlocutors. It plays a crucial role in shaping the quality of social exchanges, and begins early in development as children synchronize movements and vocalizations with their caregivers. NTs typically achieve this synchronization naturally, but autism—causing issues in processing social cues and visual-motor coordination—can throw a spanner in the works, creating another barrier to ‘clicking’ with people. Some researchers suggest that impaired mirror neuron function may contribute to these difficulties in autism, but the evidence remains inconclusive.

A number of examples of this deficit have been documented: for instance, autistic children are less prone to spontaneously rocking in sync with their caregivers (Marsh et al., 2013). In a meta-analysis of interpersonal motor synchrony in autism, Carnevali et al. (2024) found reduced synchronization in dyads consisting of autistic and NT participants, reporting an effect size of Hedge’s g = 0.85 (p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.35, 1.35], 95% PI[-0.89, 2.60]).

Fitzpatrick et al. (2017) found that spontaneous social motor synchronization was associated with responding to joint attention, cooperation, and theory of mind, whereas intentional social motor synchronization was associated with initiating joint attention and theory of mind. Additionally, social motor synchronization correlated with autism severity. Fitzpatrick et al. (2018) similarly reported that spontaneous synchrony was associated with theory of mind, while intentional synchrony was linked to attention and social responsiveness; however, facial emotion recognition was unrelated to either theory of mind or social synchrony. Granner-Shuman et al. (2021) found that lower communication skills were associated with lower intentional synchrony rates, with atypical patterns of motor planning and execution partially mediated this relationship.

These difficulties extend to other domains, such as emotional expressivity. McIntosh et al. (2006) had participants view happy and angry expressions and found that autistic participants didn’t automatically mimic facial expressions like NTs did, though both groups were able to voluntarily mimic expressions. Oberman et al. (2009) found that autistic participants’ spontaneous—but not voluntary—mimicry was delayed by 160 ms.

Yoshimura et al. (2015) reported that autistic individuals who exhibited fewer mimicry responses to dynamic facial expressions scored higher on the social dysfunction index, and Liu et al. (2023) found that mimicry performance correlated negatively with autism symptom severity and positively with theory of mind. Additionally, autistic children exhibited lower intensity in both voluntary and automatic mimicry than NT children, with theory of mind mediating the relationship between autistic symptoms and facial mimicry intensity.

Zampella et al. (2020b) had autistic and NT youth converse with their mothers and unfamiliar adults. Automated facial analysis showed that both youth and adult interlocutors exhibited less positive affect when interacting with autistic youth. Autistic youth also engaged in less affect coordination, which significantly predicted mother-rated scores on social atypicality, adaptive social skills, and empathy.

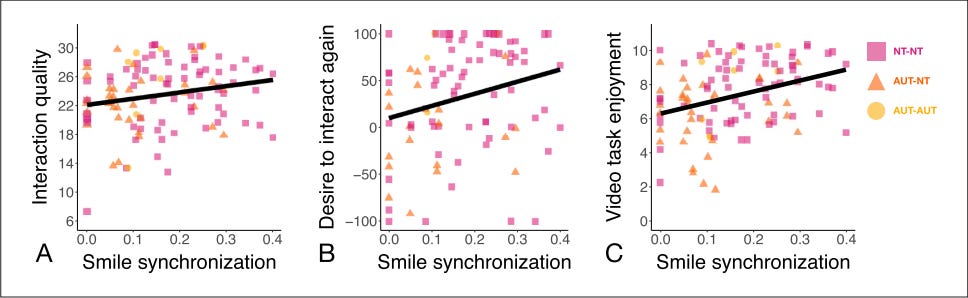

McNaughton et al. (2024) examined smiling synchronization in dyads of autistic and NT youth during a free conversation and a video-watching task. Mixed dyads displayed significantly reduced smiling synchronization compared to NT dyads, while autistic dyads didn’t significantly differ from either group. Video task enjoyment showed the same pattern. Mixed dyads reported a significantly lower desire to interact again than both other groups, but interaction quality showed no significant differences. Notably, smiling synchronization predicted the desire to interact again above and beyond the frequency of smiles.

This is consistent with the findings of Arias-Sarah et al. (2024), who conducted a speed-dating experiment using video calls where they artificially manipulated the smiles of participants in real time. They found that participants perceived their partner to be more attracted to them when the partner’s smiling was increased, and that partners were most attracted to each other when smiling was increased at the same time, rating the interactions as being of higher quality.

Deficits have also been observed in conversational synchrony. Ochi et al. (2019) found that autistic participants had significantly longer turn-taking gaps, a greater proportion of pause time, less variability, and less synchronous changes in intensity compared to NTs. Turn-taking and pausing were correlated with deficits in reciprocity.

Lahiri et al. (2022) showed that synchrony in vocal acoustics, prosody, and language use could also reliably distinguish children with and without an autism diagnosis.

This lack of synchronization is noticeable to untrained observers. Zampella et al. (2020a) showed that autistic children were perceived as significantly less socially synchronous in both verbal behaviour—indicating less balanced give-and-take and more atypical conversational pauses—and movement synchrony. Ratings in both domains were negatively correlated with autism symptom severity.

Similarly, Plank et al. (2023) presented NT participants with silent clips of dyadic conversations showing only the outlines of interlocutors. While greater leading behaviors positively influenced impressions of NT interlocutors, this wasn’t the case for autistic interlocutors, suggesting that motion energy synchrony contributes to less favorable impressions of autistic individuals.

Interpersonal synchrony has been linked to positive social outcomes and prosocial behaviours, including liking, rapport, affiliation, empathy, cooperation, and feelings of closeness (Hu et al., 2022). Several speed-dating studies have also investigated its effect on romantic attraction.

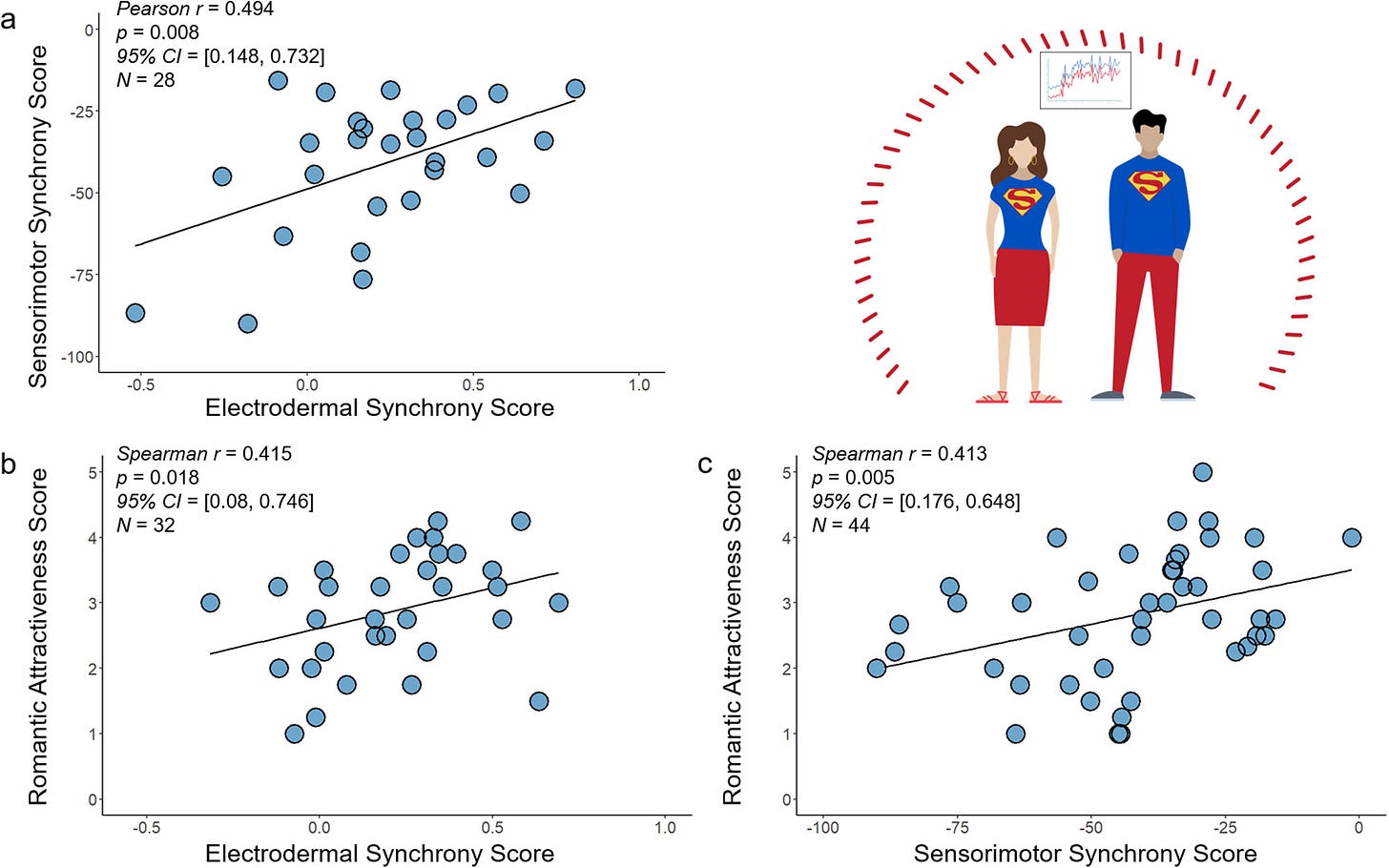

Zeevi et al. (2022) conducted a speed-dating experiment and found that electrodermal synchrony during a date was associated with mutual romantic interest (r = .51). Motor attunement (flexibility of motion leadership across the date) was also correlated with both. By combining electrodermal synchrony and motor attunement into a ‘bio-behavioural coupling’ variable and computing a linear regression model using all other data points except the predicted date, they successfully predicted the outcome of each date 71% of the time. Importantly, both electrodermal synchrony and motor attunement significantly predicted mutual romantic interest even after controlling for physical appearance11 (r = .61, p < 0.001). They also detected a gender interaction effect whereby women were more attracted to synchronous men than vice versa, and while women found synchronous men more sexually attractive, this effect was not observed in men.

Cohen et al. (2024) first conducted an experiment in which 144 participants viewed videos of a man and woman interacting with either high or low synchrony. As expected, actors in the high-synchrony condition were rated as more attractive, and the perceived attraction between them was higher.

In a speed-dating experiment including 48 students, they first tested whether initial interest in a partner predicted electrodermal synchrony during the date, but found no significant association. They then tested to what extent individual electrodermal synchrony scores (social synchrony during speed-dates) and individual sensorimotor synchrony scores (nonsocial synchrony in a finger-tapping task) were related. A significant correlation of r = .49 was found, indicating that social synchrony is rooted in general sensorimotor skills. Individual electrodermal synchrony scores correlated with romantic attractiveness scores at r = .42, and electrodermal synchrony across the entire date correlated at r = .34. Finally, sensorimotor synchrony correlated with romantic attractiveness at r = .41.

They note how studies have found that physiological synchrony is linked to improved regulation of various homeostatic systems, including temperature, immune function, heart rate, and affect. Through social regulation, humans can optimize these systems by learning to prefer synchronizing partners. This may help explain why interacting with synchronous partners—who are better able to detect and adjust to external cues—leads to smoother and more rewarding interactions.

Reverse causality is always a possibility, as feeling attraction could increase the motivation to synchronize with a partner. Zeevi et al. showed that physical attractiveness is unlikely to mediate much of the effect however, and Cohen et al. found no evidence that initial interest predicted synchrony during dates.

Intrapersonal synchrony

For autistic individuals, body language may also be out of sync with their own communication due to difficulties in processing and integrating information, and this is likely closely intertwined with interpersonal asynchrony.

Bloch et al. (2022) found that autistic participants’ nonverbal signals were temporally misaligned by an average of 55 milliseconds, and enlarged gaze-gesture delays were associated with greater intrapersonal variability in timing. Another study (Bloch et al., 2024) mapped the measured nonverbal behaviour of interlocutors with and without autism onto virtual characters, finding that just as autistic individuals’ signals are delayed, autistic nonverbal behaviour results in delayed decoding times among observers.

de Marchena & Eigsti (2010) examined spontaneous speech-gesture coordination in 15 autistic and 15 NT adolescents during a narrative task, and had observers rate the stories for communicative quality. Stories by autistic storytellers were perceived as less clear and engaging, and autism symptoms correlated negatively with story ratings. While utterance and gesture rates were comparable between groups, autistic individuals’ gestures were less synchronized with their speech, negatively impacting communicative quality. Moreover, whereas gesture frequency correlated with story ratings for NT storytellers, this wasn’t the case for autistic storytellers.

Nodding

Capps et al. (1998) reported that children with autism were able to use head nods and shakes to respond to yes–no questions, but were less likely to nod while listening. Similarly, García-Pérez et al. (2007) found that autistic participants shook and nodded their heads significantly less than NTs while the interviewer was talking, and Ochi et al. (2022) found that nodding was less frequent among autistic participants, particularly around speakers’ turn transitions. Additionally, the synchronization between nod frequency and vocal intensity was higher among NTs.

Osugi & Kawahara (2018), using clips of computer-generated figures, found that compared to the neutral or shaking figures, the nodding figures were perceived as more likeable, approachable, and attractive—though the effect was weaker for the latter.

We’ve devoted quite a lot of time to nonverbal behaviour, but of course the social challenges of autism don’t start and end there. As mentioned earlier, ‘social skills’ encompass a wide range of abilities. Now, we’ll explore other relevant aspects of autism, beginning with pragmatic language skills—the ability to use language effectively in social interactions.

Pragmatic language skills

Capps et al. (1998) found that children with autism were less likely to respond to questions and comments, contributed fewer relevant remarks, and produced fewer personal narratives.

Paul et al. (2009) compared the conversational difficulties of speakers with Asperger’s syndrome, high-functioning autism/PDD-NOS, and who were normally developing using the Pragmatic Rating Scale. Differences were found on all three major scales of Pragmatic Behaviors, Speech/Prosodic Behaviors, and Paralinguistic Behaviors. The following items were significantly different between AS and NT groups:

Irrelevant/inappropriate detail

Out of sync content/unannounced topic shifts

Unresponsive to partner cues

Little reciprocal exchange

Unusual intonation

Inappropriate use of gaze

Inappropriately formal

Topic preoccupation/perseveration

Morett et al. (2016) had 18 autistic and 23 NT adolescents watch two 4-minute clips of a cartoon and then recount them. Autistic adolescents didn’t increase their coherency and engagement in the presence of a visible listener, and greater coherency and engagement were associated with fewer social/communicative impairments. It was also found that autistic adolescents produced sparser speech and fewer gestures conveying supplementary information, and both of these effects were pronounced in the presence of a visible listener.

Larkin et al. (2017) found that autistic children and adolescents produced fewer typical communicative cues, and more cues perceived as intermittent or rote/stereotyped, even when gaze was controlled for. Among the autistic group, competence in dialogue wasn’t correlated with general language ability but was correlated with a measure of pragmatic ability.

Geelhand et al. (2021) found that both autistic and NT raters gave lower ratings to autistic speakers on all 8 scale items: relevance, referential cohesion, coherence, pedantic style, rehearsed, fluency, perseverance, and speaker typicality, with the lowest scores being found in fluency, coherence, and pedantic style.

Dolata et al. (2022) assessed autism symptoms 101 autistic, 45 ADHD, and 28 NT children in interviews and had their parents fill out the Children’s Communication Checklist, 2nd Edition (CCC-2). On all scores, autistic children scored lower than ADHD and NT children, and ADHD children tended to be somewhere in the middle, though closer to NTs. This includes the following subscales: Speech, Syntax, Semantics, Coherence, Initiation, Scripted Language, Context, and Nonverbal Communication. Moreover, effect sizes were larger for pragmatic (the last four subscales) than structural scores. Autism severity was negatively associated with the pragmatic composite, but the structural composite wasn’t significantly associated in a multiple regression model.

McGuinness et al. (2024) had 36 autistic and 36 NT children listen to conversational vignettes which manipulated the relevance and timing of responses produced by the speaker and then rate the social desirability of the speaker. They also measured the content and latency of these children’s responses. Both groups indicated that they were less likely to befriend or enjoy interacting with speakers who provided off-topic or delayed responses, but autistic children themselves provide more off-topic and fewer topic-continuing conversational responses than NT children.

Basically, as we already knew, autistic people aren’t great at talking or conversing.

Theory of mind

Another hallmark of autism is deficits in ‘theory of mind’—the ability to infer the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of other minds. From what I can tell, this is more or less synonymous with the concept of ‘cognitive empathy’. Perhaps cognitive empathy could be seen as more of an active process, while ToM represents a static ability which the application of cognitive empathy relies on.

Bottema-Beutel et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis examining the relationship between social functioning and various cognitive and developmental constructs in autistic and NT groups. While negative associations were found for all three cognitive constructs—ToM, executive function, and central coherence (reflecting a tendency to focus on details over the bigger picture)—these associations were weaker than expected. Slightly stronger associations were observed for joint attention (coordinating attention with others) and imitation, suggesting these skills may play a more significant role in social functioning.

Given the modest connection between ToM and social functioning, the authors argue that ToM may have been overemphasized as the core deficit underlying autism’s social challenges. Similarly, Schnitzler & Fuchs (2024) make the controversial argument that autism is better understood as a disorder of affective empathy. They support this claim by noting that ToM and cognitive empathy develop gradually from age two and aren’t fully formed until around four years old, whereas affective deficits—some of which were covered here, such as reduced social smiling and mimicry—are observable as early as 12 months. Additionally, social interactions rely more on implicit affective processes than explicit cognitive reasoning.

Nonetheless, ToM deficits remain and likely have interpersonal implications. A meta-analysis found a significant association between ToM and peer popularity (r = .23) and rejection (r = −.13) among children. Hudson et al. (2024) paired together 334 young adults into dyads for a cooperative LEGO building task which was videotaped and coded for behavioural indicators of ToM. ToM accuracy and motivation were assessed through lab tasks and a self-report measures, and participants rated their partners’ likeability, their enjoyment of the interaction, and changes in positive affect. The results showed that participants with a stronger ToM made better first impressions, with cognitive sensitivity—awareness and responsiveness to others’ mental states—mediating this effect.

Difficulties in intuiting others’ mental states could impact courtship, leading to missed or falsely perceived signals of attraction. Mintah & Parlow (2018) found that autistic traits predicted inappropriate courtship behaviours through ToM deficits, which also had an indirect effect through a flirtation perception bias.

Temperament

Temperament refers to individual differences in emotional reactivity and regulation, or how intensely people experience emotions and their ability to manage them. Autistic individuals tend to exhibit heightened emotional reactivity and challenges in emotional regulation from early childhood.

Northrup et al. (2024b) analyzed home videotapes of autistic and NT toddlers interacting with their parents, finding that autistic toddlers exhibited more high-intensity negative emotion, and negative emotions were more likely to persist after initiation. The effect of parent’s attempt at co-regulation appeared to be weaker for parents of autistic toddlers.

Northrup et al. (2024c) surveyed 1,864 parents of young children with autism, developmental concerns, or neither, finding that autistic children had more severe emotional dysregulation (+1.12 SD for reactivity; +0.60 SD for dysphoria). Autistic traits, sleep problems, speaking ability, and parent depression were the strongest correlates of emotional dysregulation in the autism sample.

A systematic review by Chetcuti et al. (2021) finds that autistic children and adolescents tend to differ from NT and other clinical non-autistic groups in their temperament in the following ways:

Higher in negative affectivity.

Lower in surgency (energy, sociability, approach behaviours).

Lower in effortful control (difficulty regulating impulses and emotions).

These differences are detectable as early as 6 months in high-risk infants who later develop autism.

Among autistic adults, Vuijk et al. (2018) found they tend to be:

More introverted, rigid, and passive-dependent.

Low in novelty seeking and reward dependence.

High in harm avoidance and persistence.

Low in self-directedness, low cooperativeness, and high in self-transcendence.

Restoy et al. (2024) conducted a meta-analysis on emotional regulation and dysregulation in autistic children and adolescents, finding greater challenges in the autistic group, and more maladaptive ER strategies and fewer adaptive strategies. More severe autism and poorer social skills were associated with greater ED and poorer ER skills. Another study found that alexithymia—difficulty identifying and describing emotions—partially mediated the effect of autistic traits on social skills, and fully mediated their effect on emotional regulation difficulties.

A study by Lee et al. (2017) found that observed emotion dysregulation mediated the association between ADHD and peer ratings of likeability and staff ratings of perceived peer likeability, indicating that this is another factor which could negatively affect interpersonal success.

Findings related to negative affect and emotional dysregulation should probably be expected due to autism and depression sharing common genetic risk factors. Moreover, autism, like depression, has been linked to serotonin and dopamine dysregulation. Depression is probably not sexy, either. A speed-dating study by Pe et al. (2016) found that after four minutes of interaction, participants rated partners with higher levels of depressive symptoms as less romantically attractive. While participants didn’t experience increased negative affect when interacting with more depressive partners, they experienced reduced positive affect, which led to a higher likelihood of rejection.

Sensory sensitivity

Atypical sensory processing is another well known feature of autism. Not enjoying touching will obviously not make physical intimacy any easier. Being a picky eater who can't stand noise or bright lights won't make dates any easier.