It's long been said that confidence is the key to men's success with women. Incels often complain that normies will spout hollow platitudes like ‘you just need more confidence (bro)’. This has, of course, been memed to hell and back, and is seen as a classic case of Chadsplaining: of course Chad is confident—he’s admired by all simply for existing and has girls throwing themselves at him without having to lift a finger!

Before the term incel came to prominence, late psychologist Brian Gilmartin had coined the term love-shy to describe men whose social inhibition prevented them from approaching and courting women. A popular online forum was later created around this concept.

He conducted a study involving 100 love-shy men aged 35 to 50, and 400 male university students aged 19 to 24, half who were classified love-shy. Participants completed the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, revealing that love-shy men unsurprisingly scored significantly lower in extraversion and higher in neuroticism. No difference in psychoticism was found. Older love-shy men deviated more, likely due to the attrition of less severe cases with age.

Their interpersonal difficulties weren’t confined to the romantic sphere: 73% of older and 53% of younger love-shy men reported having spent the majority of their lives without close friends, compared to none in the comparison group. In childhood, 57% of men in the comparison group had at least three close friends, compared to just 11% of the younger and none of the older love-shy men. Love-shy men had also experienced more bullying. In most cases, ‘love-shyness’ is likely just a manifestation of general shyness.

Self-identified incels have also been shown to suffer from similar social difficulties, including, as I’ve previously covered, high rates of autism. One study compared 75 incels with 54 non-incels, finding that incels reported disproportionately high social anxiety, difficulty approaching women, low self-esteem, and pessimism about partnered sexual experiences.

In this article, we will explore how confidence-related traits such as extraversion intersect with various mating outcomes to see whether confidence really is all it’s cracked up to be—or whether, as incels claim, it’s a ‘meme’.

Sexual experience

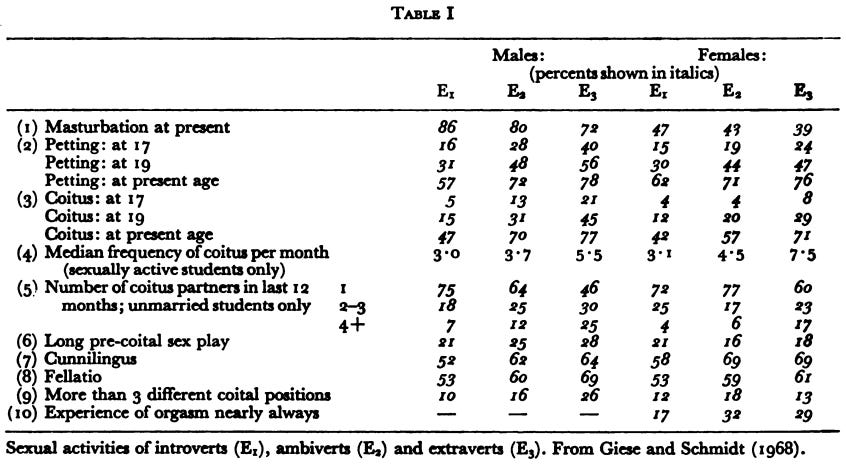

The link between extraversion and sexual behaviour was documented in the 60s by German researchers who studied about 6,000 students. Among men in the bottom 20% of extraversion, 47% had engaged in sex, compared to 77% in the top 20%. By age 17, 5% of introverts and 21% of extraverts had had in sex; by age 19, the figures rose to 15% and 45%, respectively.

Among the sexually active, the median monthly frequency of intercourse was 3 for introverts and 5.5 for extraverts. Among the unmarried, 18% of introverts and 30% of extraverts reported having 2–3 sex partners in the past year, while 7% of introverts and 25% of extraverts reported 4 or more. Extraverts were also more likely to have experienced more than three different sexual positions, and masturbated less frequently.

Barnes et al. (1984) found in a sample of 307 male university students found that extraversion was positively associated with acquiring sexual knowledge at younger ages, engaging in sex for hedonistic or novelty-driven reasons, and having experienced various different sexual acts (r = .31). Neuroticism showed no such correlation.

Schenk & Pfrang (1986) found in a sample of 498 German army recruits that extraversion was negatively associated with age at first sex (r = –.36), and positively associated with with lifetime sex partners (r = .36) and frequency of sexual intercourse in the past 6 months (r = .35). Once again, neuroticism failed to significantly predict these sexual outcomes.

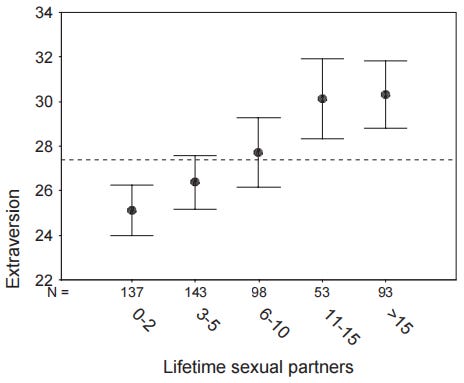

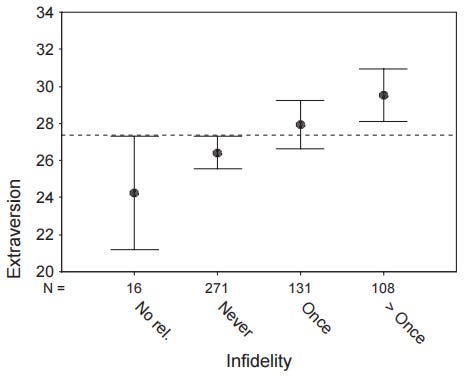

Nettle (2005) found that among British adults, extraversion predicted lifetime sexual partners, accounting for 9% of the variance (η² = .09). In the lowest quartile of extraversion, 16% of participants had 10 or more sex partners, compared to 44% in the highest. Extraversion was also associated with infidelity, but only in men—64% of men in the top quartile had engaged in extra-pair copulation, compared to 31% in the bottom. Female extraverts, on the other hand, were more likely to switch relationship partners.

Van Leeuwen & Mace (2016) analysed data from 2,877 adolescents and found that among the Big Five personality traits, extraversion was far and away the strongest predictor of having had sex by age 17.5, with an odds ratio of 2.19. Conscientiousness and emotional stability (i.e., reversed neuroticism) showed minor negative effects. Likewise, Andrae et al. (2025) analysed longitudinal data from over 5,000 German adolescents and found that as well as strongly increasing the odds of having had sex at baseline (OR = 3.31), extraversion was the strongest predictor of sexual onset, with each standard deviation increase in extraversion raising the likelihood of experiencing first intercourse at any point during the study by 42%. This effect was weaker among those whose first intercourse occurred within a relationship. Extraversion also tended to decline in the years following first intercourse. It’s possible that once it has ‘done its job’, so to speak, the drive for novelty-seeking might diminish.

Among men who remain sexually inactive well into adulthood—sometimes colloquially referred to as wizards—there appears to be a lack ‘confidence’ at the genetic level. Abdellaoui et al. (2024) examined both phenotypic and genetic correlates of lifetime sexual inactivity in approximately 400,000 UK residents aged 39 to 73. Among phenotypic traits, nervousness was positively associated with virginity in men (but showed no effect in women). Risk-taking and substance use were negatively associated. Regarding polygenic scores, extraversion, risk-taking, substance use, and frequency of friend or family visits all showed negative associations, while autism spectrum traits showed a positive one. Interestingly however, neuroticism and anxiety also showed negative associations.

Less confident men are also more likely to hire a prostitute for their first sexual encounter. Figueira et al. (2001) found that 58% of men with social anxiety reported a prostitute as their first sexual partner, compared to just 14% of men with panic disorder. They were also less likely to have a current sex partner (0% vs. 32%). Similarly, Bodinger et al. (2002) found that men with social anxiety not only reported a later age at first sex, but also a higher number of paid sexual partners, and were more likely to have had only paid partners.

Meta-analysis on number of sex partners

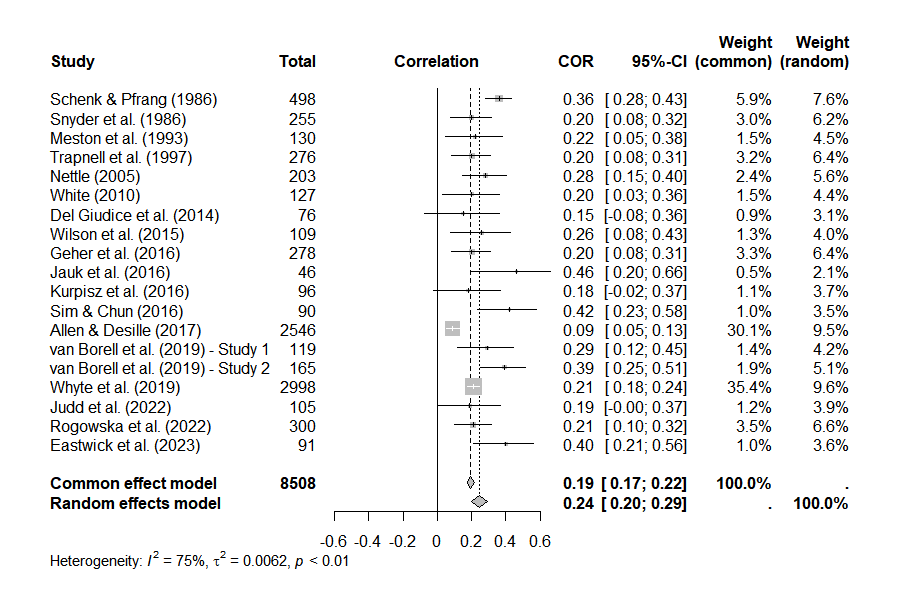

I conducted a meta-analysis of studies that included correlations or downloadable data on extraversion and sexual partner count, using male data only. Generally the outcome measure is lifetime sex partners, although in other cases it’s SOI-B (sociosexual behaviour).1

The random-effects estimate was r = .24, accounting for roughly 6% of the variance. The effect may be stronger for men; Allen & Desille (2017)2, Whyte et al. (2019), and Rogowska et al. (2022)3 all found significant sex interactions.

Relationships

Himadi et al. (1980) compared 12 ‘high-dater’ and 12 ‘low-dater’ men and found:

High-daters scored significantly higher in extraversion, lower in neuroticism, and lower on the social avoidance and distress scale.

Peer ratings indicated that high-daters were more socially active, though there was no significant difference in physical attractiveness.

After ten-minute interactions, low-daters gave themselves higher ratings for social anxiety following opposite-sex interactions, and were given higher ratings for social anxiety and lower ratings for social skill following same-sex interactions.

They were also rated by opposite-sex peers as more socially anxious and less interactive, and by same-sex peers as more socially anxious.

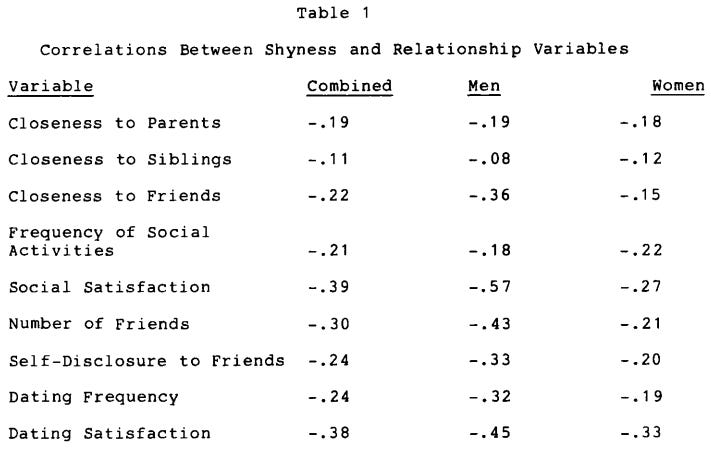

Jones & Briggs (1984) reported data from several studies. In one, alongside less social activity and social satisfaction, shyness predicted both lower dating frequency and dating satisfaction.

Leck (2006) studied 175 undergrads and found that both lifetime number of dates and satisfaction with dating frequency correlated negatively with shyness and introversion. For men, observer-rated social skills were positively associated with lifetime dates. Shyness and introversion didn’t significantly correlate with physical attractiveness as judged from video or photograph, although observer-rated social skills were positively associated with men's video-rated attractiveness.

Neyer & Asendorpf (2001) and Neyer & Lenhart (2007) analysed longitudinal data of German young adults. At baseline, singles were lower in extraversion (d = .31), higher in shyness (d = .31), higher in neuroticism (d = .34), lower in self-esteem (d = .41), and lower in conscientiousness (d = .2) compared to those in relationships. Interestingly, higher neuroticism not only predicted being single, but among those in relationships, an earlier relationship start. This may reflect a stronger need for closeness and attachment, coupled with difficulty securing and maintaining it due to anxious and volatile tendencies. Personality development was moderated by transition to partnership: individuals who entered a partnership became less neurotic and shy, and more extraverted, conscientious, and self-confident. In contrast, those who remained single showed little change, suggesting that personality differences between singles and partnered individuals may grow over time.

Stavrova & Ehlebracht (2015) analysed the German Socio-Economic Panel—a large longitudinal dataset, selecting individuals who were single at each survey wave. Among all the variables in the regression model, extraversion had the greatest effect on the likelihood of finding a partner in the following year. This was independent of social involvement, which also had a positive effect.

Wagner et al. (2015) analysed another German longitudinal survey of young adults. Compared to those with previous partnership experience, individuals without such experience were significantly more neurotic (d = .23), less extraverted (d = .48), had lower life satisfaction (d = .33), lower self-esteem (d = .33), and were more depressed (d = .2). Experiencing a first romantic partnership had a medium-sized effect on self-esteem (d = .47), along with smaller effects on neuroticism (d = .33), extraversion (d = .2).

Erevik et al. (2020) collected data through two online surveys of Norwegian students a year apart. Among the 2,404 participants who were single at T1, Extraversion predicted entering a relationship over the next year, with an odds ratio of 1.58 for men and 1.20 for women. There was a sex interaction whereby neuroticism positively predicted relationship formation for women but had a nonsignificant negative effect for men. Openness on the other hand predicted relationship formation only for men.

Apostolou & Tsangari (2022) studied 1,418 Greek-speaking participants and found that lower extraversion was associated with a higher likelihood of being involuntarily single: each unit increase in extraversion increased the odds of being in a relationship rather than involuntarily single by 40.3%, and to be ‘between relationships’ rather than involuntarily single category by 38.5%. When participants were grouped into low, moderate, and high extraversion, those low in extraversion were 2.22 times more likely—and those moderately extraverted 1.66 times more likely—than highly extraverted individuals to be involuntarily single rather than in a relationship. Introverts also tended to experience longer spells of singleness: each unit increase in extraversion was associated with a 2.19-year reduction in the length of singlehood. Notably, extraversion had no effect on the odds of preferring to be single, suggesting that introversion was linked to unwanted singleness.

Bühler et al. (2022) analysed three nationally representative samples, finding:

Higher extraversion and openness predicted beginning a relationship, moving in with the partner, and (alongside agreeableness) marrying.

Higher extraversion and openness and lower neuroticism and conscientiousness were associated with separation, but no effects were observed for divorce or widowhood.

Marriage predicted significant decreases in extraversion, while separation predicted an increase in agreeableness. No significant socialization effects were observed for beginning a relationship, moving in with a partner, divorce, or widowhood.

Hoan & MacDonald (2024) surveyed two samples recruited online (combined N = 1,811). Single individuals were lower in extraversion (d = .34/.27) and and higher in neuroticism (d = –.16/–.13). Differences were present in all the facets of extraversion measured (sociability, assertiveness, and energy level), but for neuroticism it was present in the depression facet, but not the anxiety or emotional volatility facets. This aligns with consistent findings that people in relationships tend to be happier—a pattern likely due in part to relationships genuinely fostering happiness, though the association may be bidirectional.

Stern et al. (2024) analysed a survey of 77,000 older adults across 27 European countries, comparing the personality traits of forever alone lifelong singles with those who had ever been partnered. Participants who had never been partnered, cohabited, or married were significantly lower in extraversion. While there was no overall difference in neuroticism, significant differences emerged for men, younger individuals, and in countries with higher proportions of singles or men.

Within-relationship effects

Studies tend to show small positive actor effects4 of emotional stability on relationship satisfaction, as well as very small effects of extraversion. Partner effects5 have also been observed, though they are typically weaker still and aren’t consistently seen for extraversion (Dyrenforth et al., 2010; Furler et al., 2013; van Scheppingen et al., 2019). Similarity effects are rarely detected, and assortative mating on extraversion and neuroticism is also weak.

In a meta-analysis of personality and divorce risk, Spikic & Mortelmans (2021) found a very small positive effect of extraversion (g = .1), which wasn’t robust to publication bias. Neuroticism had a small more robust effect (g = .24).

Jirjahn & Ottenbacher (2023), analysing partnered individuals in a large German dataset, found that extraversion was associated with higher sexual satisfaction, increased sexual frequency, and a greater likelihood of infidelity. Neuroticism was associated with lower sexual satisfaction, decreased sexual frequency, less satisfaction with current sexual frequency, and also a greater likelihood of infidelity.

Reproduction

Jokela et al. (2009) analysed a longitudinal Finnish dataset of men and women who were followed for 9 years (N = 1,839). They found that high emotionality decreased the probability of having children, whereas high sociability increased it. High activity increased the probability for men specifically. Parenthood, in turn, predicted increases in emotionality—particularly among individuals who were already high in emotionality and those with two or more children. Among men, having children increased sociability for those high in sociability at baseline but decreased it for those low in sociability.

When sociability and emotionality were entered simultaneously in the model, only sociability predicted having a first or second child, while only emotionality predicted having a third. For men, both sociability and activity independently predicted having a first and second child. Finally, the likelihood of cohabiting with a partner increased by approximately 4% per standard deviation increase in sociability and activity and decreased by about 3% per standard deviation increase in emotionality.

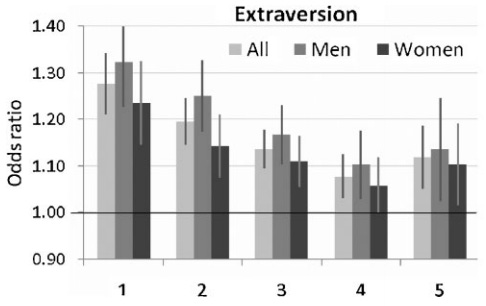

Jokela et al. (2011) analysed data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study and the Midlife Development in the United States (combined N = 15,729), with personality and reproductive history reported at an average participant age of 53.

Extraversion was the strongest predictor of first marriage: OR = 1.53 for men and OR = 1.22 for women. Neuroticism had a small negative effect for men (OR = 0.9), but not for women.

Extraversion predicted a younger age at first marriage: β = –.43 for men and –.28 for women. Neuroticism had no effect.

Extraversion increased the odds of having a first child: OR = 1.34 for men and 1.23 for women. Neuroticism had no effect.

Extraversion predicted younger age at first childbirth: β = –.32 for men and –.19 for women. Neuroticism had a negative effect for women (β = –.1).

Extraversion predicted number of children for men (β = .15) and women (β = .1). Neuroticism had a negative effect that was only significant among women, except for a small –.05 effect in one of the models for men.

The effect of extraversion was smaller among those who already had at least one child, but remained significant for men, and after adjusting for ever being married and age at first marriage.

Extraversion predicted childbearing more strongly in unmarried (OR = 1.13) than in married (OR = 1.03) individuals—perhaps reflecting higher sociability or promiscuity leading to more unplanned children. Neuroticism predicted lower odds of childbearing only in unmarried men (OR = 0.87).

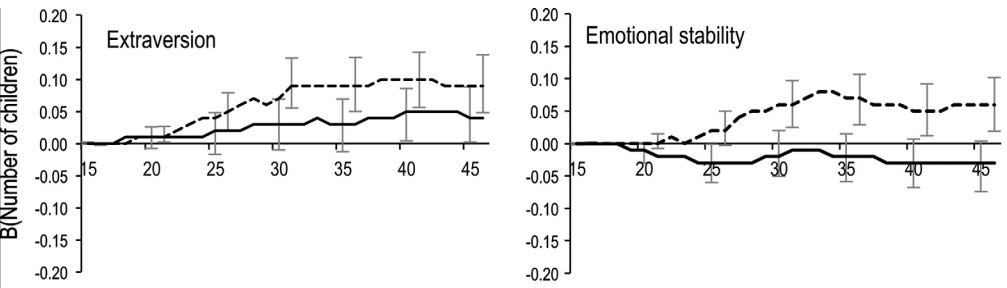

Berg et al. (2013) analysed data from the 1958 British birth cohort study (N = 8,336).

Planned pregnancies were more likely among men (but not women) higher in extraversion and emotional stability.

Non-planned pregnancies were more likely among men and women higher in extraversion, and among women lower in emotional stability.

Extraversion predicted a higher number of children, especially among men. A one SD increase in extraversion predicted an increase of 0.09 children for men. Emotional stability also predicted more children among men, but not women.

In men, the positive effects of extraversion and emotional stability on number of children peaked slightly after age 30, remaining stable thereafter.

Van Scheppingen et al. (2016) analysed a longitudinal Australian dataset, focusing on individuals aged 17 to 45 who were childless in 2005 (N = 2,469; mean age = 26.7). Controlling for age and relationship status, extraversion significantly predicted parenthood in both men (OR = 1.29) and women (OR = 1.18). Neuroticism was not a significant predictor.

Kasaeian et al. (2019) conducted an online survey (N = 1,843) and found that extraversion positively predicted number of children in a multiple regression analysis (β = .052, p = .008).

Whyte et al. (2019) analysed data from an online survey advertised on an Australian dating website (N male = 2,998; N female = 1,480). Extraversion correlated with number of offspring for men only.

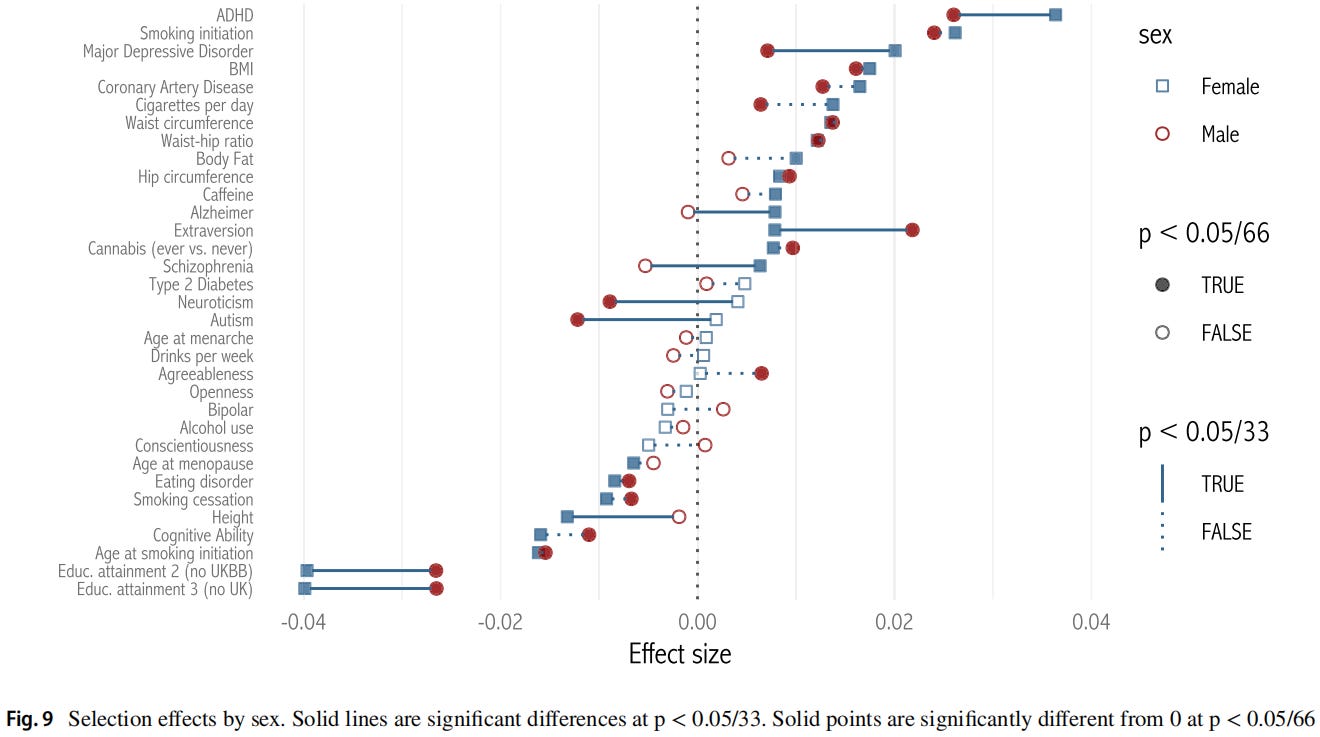

Hugh-Jones & Abdeoulli (2022) examined UK Biobank data from 409,629 White British individuals to assess how polygenic scores for various traits predicted fertility. Extraversion was positively associated with fertility, and had a larger effect for men, while neuroticism negatively predicted fertility only in men.

Peters (2023) analysed data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (2005–2017; N = 5,758). Extraversion was positively associated with the likelihood of having a first child, but negatively with the likelihood of having a second child, with significant effects observed only among men.

Skirbekk & Blekesaune (2014) analysed a Norwegian survey of men and women born between 1927 and 1968 (N = 7,017). Extraversion increased fertility among men, while neuroticism reduced it—but only in the younger cohorts. Despite the abstract stating that extraversion increased fertility in both sexes, these traits didn’t appear to significantly affect women’s fertility.

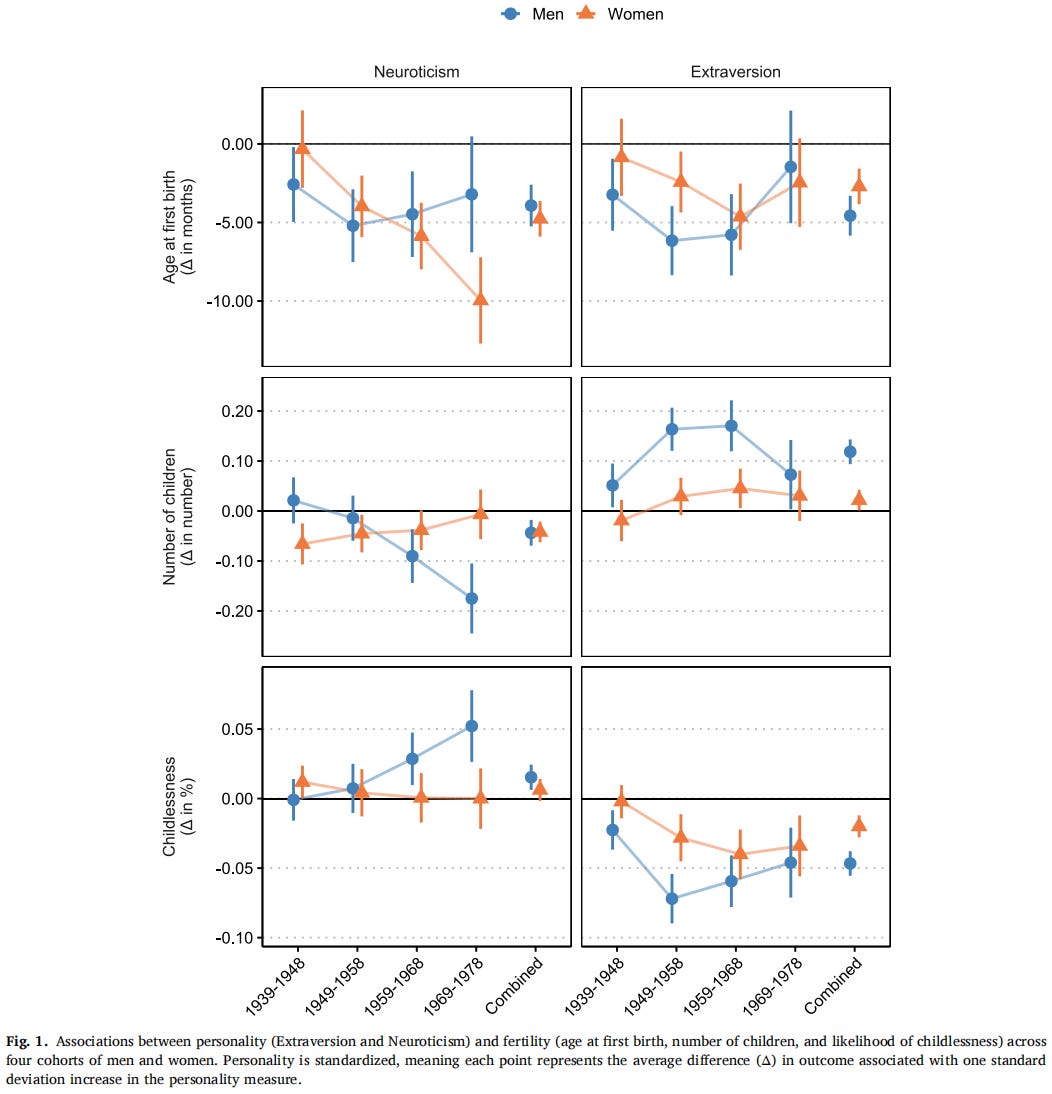

Skirbekk et al. (2025) analysed another Norwegian survey combined with birth records (N = 27,585). Extraversion was associated with an earlier age at first birth, a higher number of children ever born, and a lower rate of childlessness—effects which were stronger for men. Neuroticism was also associated with an earlier age at first birth, but a lesser number of children ever born and a higher rate of childlessness. The effect of neuroticism had generally become stronger in younger cohorts, where for number of children and childlessness it was observed only in men.

Extraversion’s effect has also been observed in a nonindustrial population: Alvergne et al. (2010) studied traditional villages in rural Senegal, finding that among men, extraversion was associated with a higher likelihood of polygynous marriage (r = .28, p = 0.01); men with above-median extraversion were 40% more likely to have more than one wife. Extraversion was also positively associated with total number of children (r = .27, p < 0.05); men with above-median extraversion had 14% more children. Including marital status or social class in the model rendered the effect nonsignificant. Among women, higher neuroticism was associated with having more living children.

Causes

Extraversion is consistently linked to a range of outcomes related to sexual experience, relationships, and reproductive output, while neuroticism shows smaller and less consistent effects. The question naturally turns to what mechanisms drive these associations.

Socialisation

A common assumption is that if a trait influences mating outcomes, it must be because of the sexual market value it confers. Traits are typically discussed in terms of how much women ‘care’ about them. However, desirability is only one path to success.

Extraverts are exuberant party animals—outwardly oriented, they seek stimulation and new connections. This leads to larger social networks and a systematic overrepresentation of extraverts within them. Nettle (2005) also found that extraversion was correlated with time spent in social activities (r = .45) and enjoyment of travel (r = .27).

Another intuitive link is that between extraversion and alcohol consumption, and between alcohol and risky sexual behaviour.6 One study found that extraverts experienced greater mood enhancement from alcohol, which was mediated by group members’ smiling and reciprocal sharing.

This is likely the most straightforward explanation: extraverts engage with more people—who themselves are more extraverted on average—naturally granting them more opportunities to meet potential partners. Sexual activity is, of course, socially mediated. Lucas et al. (2020) found that social withdrawal at age 12 predicted delayed sexual debut, both directly and indirectly through three mediators: self-perceived social competence, other-gender friendships, and romantic relationships.

Extraverts are also more assertive and risk-tolerant; they have less fear of rejection. Since dates are typically initiated by men, the simple fact is that the guy who persistently shoots his shot and takes rejections on the chin will outperform the one who rots in his room all day spinning conspiracies about bogeychad, unless perhaps there is a very large attractiveness disparity and the rotter has good success online.

Desirability

Nonetheless, people do seem to be more drawn to extraverts. This has been consistently observed in peer ratings of students’ likeability and popularity, with one study suggesting that extraversion particularly enhances liking among opposite-sex peers. Szczygiel & Mikolajczak (2018) found that this positive association held for adolescents with high but not low interpersonal emotional competence.

Of the Big Five traits, extraversion shows the highest consensus at zero acquaintance, and these judgments predict future behaviour. It has also been shown to predict favourable impressions in first impression contexts.

Friedman et al. (1988) had 54 undergrads complete several personality and social skills measures before being videotaped during a brief interaction. Separate groups of judges rated their likeability and physical attractiveness. Scores on the Affective Communication Test, the extraversion and acting subscales of the Self-Monitoring Scale, and the extraversion subscale of the Eysenck Personality Inventory all positively correlated with likeability. The effect of physical attractiveness wasn’t statistically significant, and ACT and SMS-extraversion scores remained significant even after controlling for attractiveness ratings.

Berrios et al. (2015) conducted a speed-dating experiment and found that individuals higher in extraversion elicited more ‘positive affective presence’ in partners, which accounted for the effect of perceived responsiveness on romantic interest. Humberg et al. (2023) also analysed speed-dating data, which showed that extraversion increased initial attraction (r = .22 for men and .16 for women). There was a sex interaction for neuroticism whereby it reduced men’s desirability (r = −.18) but had no effect for women. There was no evidence for personality similarity effects, and no actor effect of extraversion—i.e., extraverted people were not more or less attracted to their partners.

Dominant behaviour has been linked to perceptions of attractiveness. Vacharkulksemsuk et al. (2016) found that postural expansiveness—think manspreading—predicted success in speed-dating, with each one-unit increase nearly doubling the odds of receiving a ‘yes’. In a follow-up experiment using online dating profiles, expansive postures increased the likelihood of selection, especially for men’s photos, with perceived dominance partially mediating the effect.

Wu et al. (2016) took a novel approach, showing in a speed-dating experiment that a polymorphism in a serotonin receptor gene linked to social dominance and leadership positively predicted men’s success, whereas a polymorphism in an opioid receptor gene linked to social sensitivity and submissiveness had the opposite effect. Notably, both effects were reversed for women.

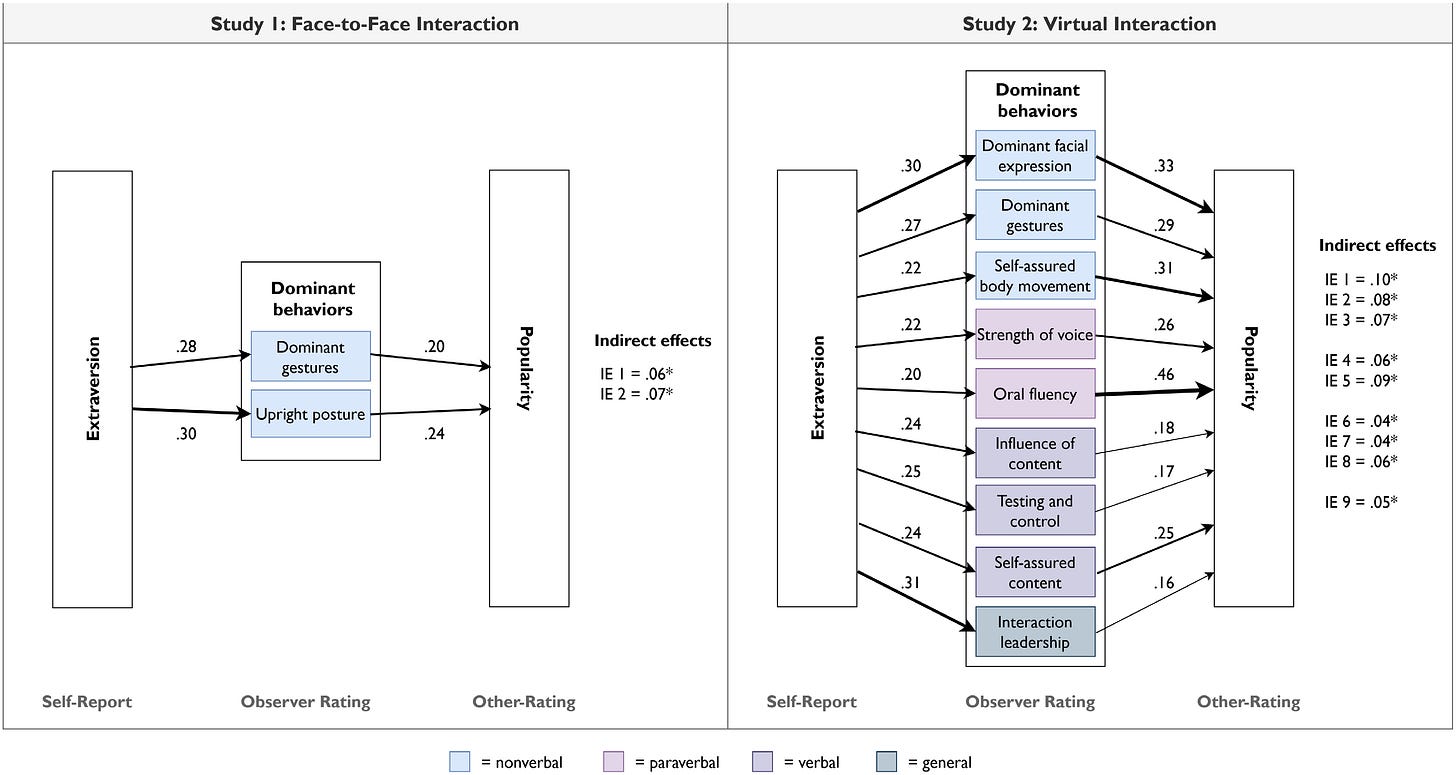

Buss et al. (2024) replicated previous findings that extraversion7 is consistently associated with greater popularity at zero acquaintance and further demonstrated that this was partially mediated by observed dominant behaviour.

While distinct constructs, extraversion is associated with greater emotional expressivity across both self-report and behavioural measures—though the former shows a stronger correlation. Expressivity refers to the ability to nonverbally convey communicate emotion through facial expressions and gestures, as well as a general tendency to be outwardly expressive. It plays a central role in impression management and what we call ‘charisma’. The Joker and Batman occupy opposite ends of the expressive spectrum, and it’s clear which one is the audience favourite. I’ve previously covered expressivity’s effect on first impressions in this article on autism. Extraverts are also better at decoding others’ nonverbal cues, which should lead to fewer missed or misinterpreted signals of interest.

Desire

It’s also possible that extraverts aren’t only more desired, but also desire more. One facet of extraversion is excitement seeking, which psychologist Hans Eysenck theorised was paradoxically driven by extraverts being chronically under-aroused. Several neuroimaging studies seem to agree with this, showing reduced resting-state brain activity in extraverts, which may drive them to seek out stimulating experiences in order to ‘feel alive’. They may also have more reactive dopamine reward systems, reinforcing this drive.

A number of studies have documented a connection between extraversion and sexual desire. Heaven (2000) found that extraversion was associated with greater sexual curiosity and excitement and with less sexual nervousness. Nettle (2005) reported a correlation between extraversion and interest in sex (r = .21), though not with the number of sex partners desired over the next two years.

Schmitt & Shackelford (2008) surveyed 13,243 people across 46 nations and found that, among men, extraversion was modestly correlated with short-term mating interests (r = .09), unrestricted sociosexual orientation (.16), mate poaching attempts (.15), succumbing to poaching (.07), and lack of relationship exclusivity (.1). Similarly, Whyte et al. (2019) found among a sample of 2,998 Australian males an association between extraversion and sociosexual attitude (r = .08) and desire (.09). So there’s probably something there, but likely only enough to serve as a small mediator.

Of course, as we’ve seen, extraversion isn’t just associated with greater promiscuity, but also to a greater likelihood of entering or being in a relationship and having not just more unplanned but also planned children. Holtzman & Strube (2013) found that extraversion was associated with both short- and long-term mating orientations, describing this as a ‘dual strategy’. Likewise, while conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability seem to consistently align with a slower life history strategy, extraversion and openness appear less straightforward, and different facets of each construct may be differentially related to fast and slow strategies. It might be that the trade-offs between investment in short- and long-term mating aren’t as sharp as typically assumed.

Is it looks?

This information might not be terribly controversial to many, with incels being a notable exception. This group tends to take issue with it as it clashes with their morphological reductionist presupposition. Though they’re keen to emphasise the importance of genes, what they mean by the term is simply physical morphology. At least when it comes to personality, they become staunch environmental determinists, adopting a blank slate view of psychology. Their contention is that extraverts are only that way because they’re Chads, and thus beneficiaries of an endless stream of positive attention and reinforcement that over time builds their confidence—whereas the reverse is true for unattractive people.

One immediate issue with this explanation is that extraversion has a stronger association with lifetime sex partners than does physical attractiveness.

Contrary to common intuition—and to what the incel model of personality would predict—there is also very little association between physical attractiveness and confidence.

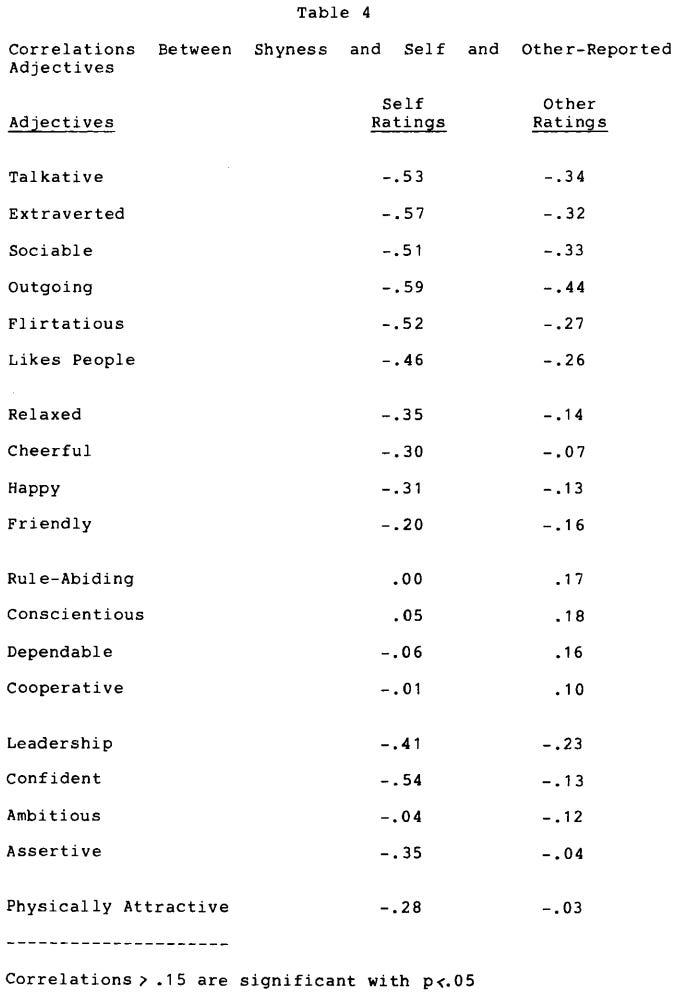

In another study described by Jones & Briggs (1984) for instance, college students completed five measures of shyness, rated themselves on a set of adjectives, and then had several acquaintances rate them on the same adjectives. Shyness was typically negatively correlated with both self- and other-ratings of adjectives such as extraverted and outgoing, with generally stronger correlations for self-ratings. It was also negatively correlated with self-rated attractiveness (r = −.28), but not with other-rated attractiveness. While shy individuals were accurately perceived as less extraverted, they weren’t perceived as less attractive—suggesting they held unduly negative views of their looks.

There are many similar examples, which I’ve already covered in depth here. Studies consistently show little to no relationship between observer-rated attractiveness and psychological traits or conditions such as extraversion, neuroticism, social anxiety, and depression. It’s only when people rate their own physical attractiveness that consistent associations emerge. Clearly, the lookism narrative would predict correlations with observer ratings, as it’s external treatment that is said to drive psychological outcomes. Beyond that, here are a couple of key studies I’d consider compelling falsifications of the narrative.

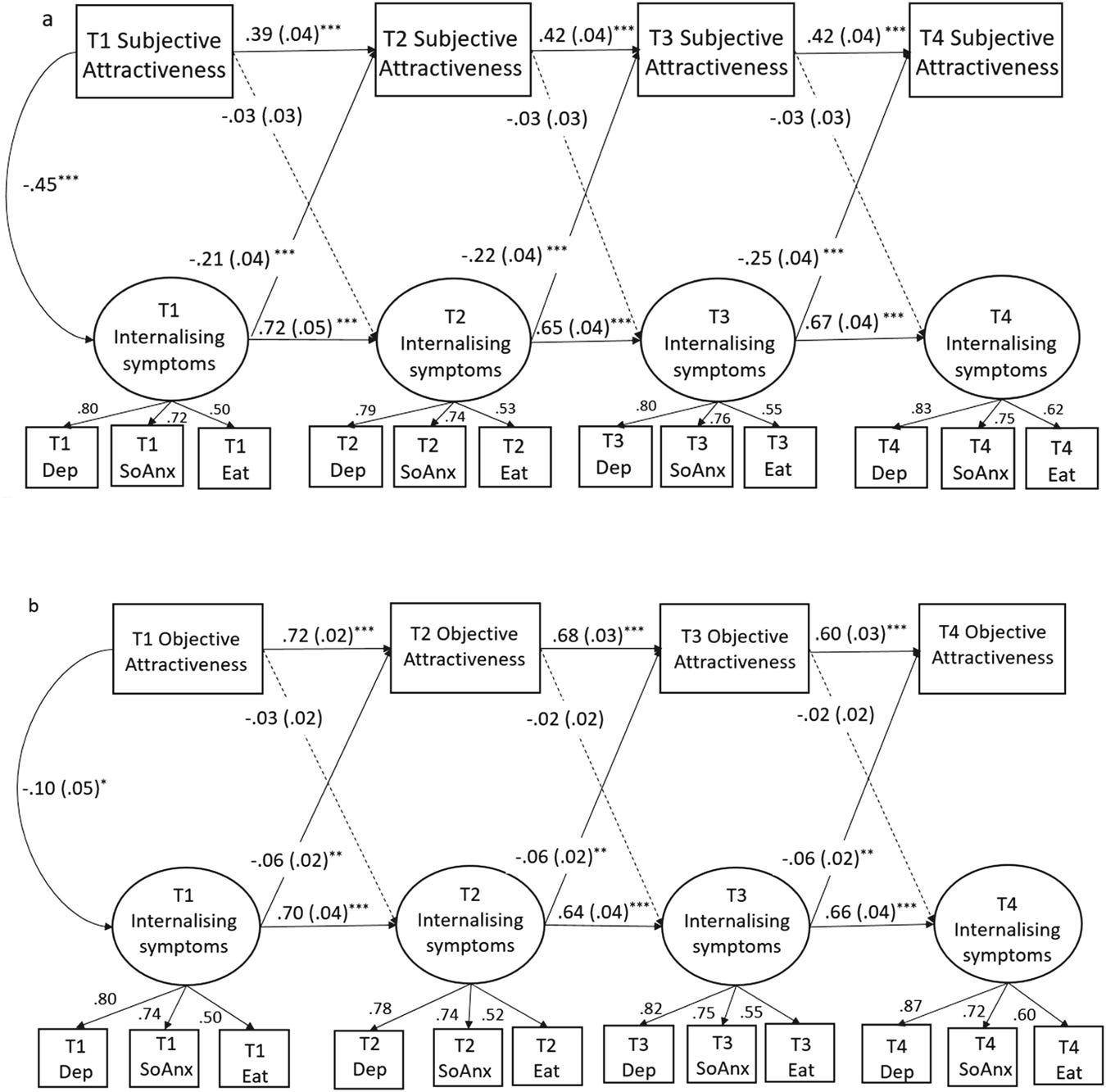

Magson et al. (2023) conducted a longitudinal study of 528 adolescents. They replicated prior findings by showing negligible and mostly non-significant correlations between observer-rated attractiveness and mental health outcomes, alongside moderate correlations with self-rated attractiveness. Most notably, while neither changes in subjective nor objective attractiveness over the years predicted later changes in depression, social anxiety, and eating pathology, changes in these internalising symptoms predicted changes in subjective—and even to some extent objective—attractiveness. Basically, it’s all in your head, bro.

These results hint at reverse causality: people who lack confidence may appear less attractive due to self-neglect or subtle nonverbal cues, while extraverts tend to be more status-driven and engage more in self-enhancement. One study found that being well-groomed mediated the link between extraversion and perceived physical attractiveness.

Haysom et al. (2015) analysed data from 1,455 twins. While small correlations between attractiveness and extraversion were found for males (r = .11) and females (r = .18)8, the genetic variation underlying attractiveness accounted for only a negligible and nonsignificant portion of the variance in extraversion for either sex (0.5–2.4%).

Research has shown that extraversion can be perceived even after brief exposure to faces. Little & Perrett (2007) showed that composite images of faces high in extraversion were accurately identified as such, though they weren’t rated as more or less attractive than those low in extraversion. Instead, a study by Borkenau et al. (2009) found that self-other agreement for extraversion was mostly mediated by the cheerfulness of facial expressions, with particularly strong correlations for self-reported excitement-seeking and positive emotions.

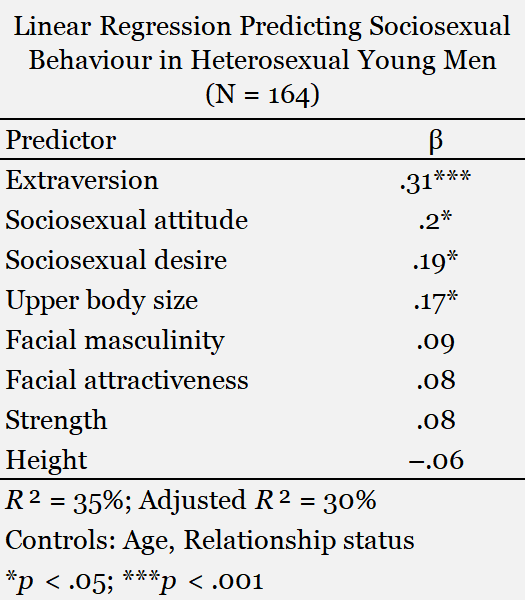

The dataset from Study 2 of von Borell et al. (2019) contains a number of variables that allow us to conveniently assess whether extraversion predicts men’s sexual success above and beyond morphology. A regression model including extraversion, sociosexual attitude & desire, facial attractiveness, height, strength, upper body size, facial masculinity, age, and relationship status revealed that extraversion had the strongest unique effect on sociosexual behaviour, followed by sociosexual attitude, desire, and upper body size. Facial attractiveness only correlated at r = .09 with extraversion and didn’t moderate its effect (it had a similarly strong effect for unattractive and attractive men).

Conclusion

There is a fair amount of online discourse about which traits best predict men’s ‘sexual success’: looks, money, status, confidence? Contrary to the common trope that the ‘hot guy gets all the girls’, attractiveness explains only about 2% of the variance in number of sexual partners, with height accounting for less than 1%. There’s also no indication that these effects have grown stronger post-dating apps. While its effect size is also small—highlighting the inherent difficulty of predicting human behaviour—extraversion nonetheless accounts for more than twice the combined influence of attractiveness and height.9 Of course body count is a narrow definition of ‘sexual success’, and physically attractive men of average extraversion probably have more sex with attractive women than do extraverted men of average looks.

While evidence suggests that extraverts’ charisma makes them more desirable, it’s not necessary to argue that this effect surpasses that of physical attractiveness to explain its larger effect on mating outcomes, because unlike morphology, it operates through multiple pathways—it's not just about what you have, but how you use it.

Neuroticism’s effects were less clear-cut, but there may be a modest negative impact on men’s relationship and reproductive outcomes. Its neutral association with lifetime sex partners could reflect neurotics’ unstable behaviour leading to more relationships failing and having to find new ones while also finding it harder to do so.

The issue with the phrase ‘just be confident, bro’ clearly isn’t that confidence doesn’t help or only benefits Chad, but lies instead with the word just. Part of why incels resist the notion that agentic behaviour matters might be that it feels accusatory—implying it’s more your ‘fault’ if you lack success. Unlike other handicaps, introversion is less clearly intrinsic, leading many to believe that all it takes is a mindset shift, that all that’s needed is to think better thoughts and act on them. But confidence can’t simply be pulled out of a hat; ultimately, behaviour must arise from gene-environment interactions.

Confident people need not necessarily have an objectively good ‘reason’ to be so, either. Heritability estimates for personality often hover around 50%, but typically rely solely on self-reports, which again, are prone to measurement error. When instead the shared variance between self- and informant-ratings are examined, heritability estimates rise to between some two-thirds and four-fifths.10 Personality also shows considerable rank-order stability, especially in adulthood, and most shy infants tend to remain shy into adolescence.

I’m not about to start shilling a PUA course or anything, but one thing they get right is that you generally do have to put yourself out there and talk to people. A common rejoinder is that everyone meets online now, so the only bottleneck is morphology. This is false: about three-quarters still meet offline—and if anything, the rate is higher among younger individuals who are more likely to have been more recently active in social environments. And if you do manage to arrange a date, confidence and social skills can still affect how it plays out.

If extraversion is seemingly so adaptive, why aren’t we all high in it? The answer usually lies in trade-offs: being too bold or active can get you in hot water. Nettle (2005) found that extraversion increased the likelihood of hospitalization for accident or illness. It is also associated with engaging in more violence. Deng et al. (2021) found a curvilinear effects, with increases in social acceptance and decreases in depressive symptoms levelling off at high levels of extraversion. It might be that excessively extraverted people can come across as narcissistic attention seekers. Moreover, extraversion also tends to be lower in regions with historically high pathogen loads, reflecting variable environmental optima. Until recently, it may have been under stabilising selection, but as life becomes generally safer and society more tolerant of extraverted behaviour, extraverts may more freely reap the rewards of hypersociality and hyperactivity. If men are increasingly reluctant or have fewer opportunities to meet women, the advantage held by extraverted men may only become more apparent. In a more atomised society, extraversion could come under stronger selection pressure as those on the lower end begin to fall through the cracks.

There is also mutation–selection balance: a certain amount of variation will exist just due to new mutations arising faster than selection can eliminate them.

Since the obsession with jawlines and height took hold, personality has been steadily marginalised and dismissed as ‘cope’. Incels coined the clever meme term pERsonality to mock it—somewhat ironically, given what we know about Elliot Rodger, for whom a range of copes have been trotted out (such as his mixed-race background or medium height) to avoid more the obvious conclusion. Its lesser appeal relative to the ‘black pill’ may be in part due to lacking a ‘grand narrative’ to rally around, and explanations that are seen as pointing more inward don’t fire people up as much as those that point outward. Whatever the case, we can confidently say that personality does matter. What this doesn’t mean, of course, is that ‘just being yourself’ is a success guarantee—and whether this is really a more hopeful ‘white pill’ counterpart to the ‘black pill’, as often assumed, remains highly debatable.

This is comprised of three items: number of partners in the past year, lifetime one-night stand partners, and lifetime partners with no long-term intent.

The relatively modest effect in this study may be partially attributable to the older age of participants, who were in their mid-60s when surveyed in 2010–12.

I also tested the difference in extraversion between virgins and non-virgins after retrieving the raw data from Rogowska et al. For men, the difference was d = .72—twice that of physical attractiveness. For women, it was d = .39.

The effect of one’s own traits on one’s own outcomes.

The effect of one’s partner's traits on one’s own outcomes.

Early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and having multiple sexual partners.

Of the facets assertiveness, sociability, and activity, the first two were associated.

Though none between height or BMI and extraversion.

This should also be considered a lower-bound estimate, as self-reported personality measures are prone to measurement error—typically more than facial attractiveness ratings, which usually aggregate ratings from multiple independent judges. Correcting for this could strengthen the relationship. For instance, Connolly & Ones (2010) found that observer ratings of personality added predictive value to academic and job performance beyond self-ratings.

This doesn’t necessarily have to mean that personality is highly immutable. For example, if everyone lost the same amount of weight through Ozempic, it wouldn’t affect the variance explained by genes. Similarly, if only 1% of people had access to it, heritability estimates would still change little, even if it was effective for those individuals. Still, it’s a good indicator that genes play a substantial role. The drive and ability to change likely have genetic influences as well.

“Risk-taking and substance use were negatively associated.”

Me ripping a cig on the bike at every red light to increase my random bj odds

Great post! It sounds so silly but it took me a lot of years to realize that my complete lack of success with women was not because of my height or race, but because I was not talking to them at all. If I did, I made no moves. It was following your work that helped me feel better about myself and take more action because I no longer believed I was a bad partner.

I would love to see a post on physique. I wonder if an unspoken idea behind a lot of the angst behind people who subscribe to black pill and related ideologies is that they're just not able (in their current state) to get the hot girls to like them. So then the comforting truth that there is likely someone who matches them (as a lower quality mate) who might like them exists out there backfires because it's either hot girl or no girl in their eyes.

I think physique would be interesting an interesting subject to read your take on because I recently started to lose body fat. I had a lot of muscle prior from years of intentionally bulking and really high body fat. I've always been a nice person, pretty good personality traits, had a job making six figures, socialized a lot, lots of friends, but I recently lost my wizard status and got laid after shedding about 12 pounds of bodyfat. And the attention from really attractive women has increased significantly with this being the only change I've really made.

I was delayed in losing my virginity for many reasons but a big one was that I used to get attention from really cute girls in school when I was skinny so I always thought I could get those girls. Then I got chubby but muscular, and improved all other facets of my life, but I could never seem to get the attention of the women I liked again until I started getting leaner (and much better groomed). Now that I'm leaner I feel like I have so much more attention from the women I desire and I do wonder if that mismatch between what someone thinks they should be getting combined with a neurotic/perfectionist outlook creates a believer in the black pill.